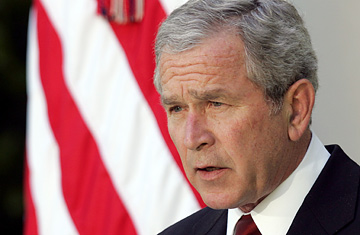

President George W. Bush speaks on the climate in the Rose Garden of the White House.

Who do you think is the most environmental President in American history? Bill Clinton, who used his executive authority to create 17 new national parks without congressional approval? Or Jimmy Carter, who in only four years protected more land than Clinton, and supported what would become the Superfund toxic waste cleanup law? (To those of you who would say Al Gore, well, it might be time to let that one go.) Whoever might claim the title, surely it would have to be a Democrat — since everyone knows that Democrats are tree-huggers, and Republicans see the Earth as something that gets in the way of oil, right?

Here's an unorthodox candidate for the title of America's greenest President: Richard Milhous Nixon. It was the arch-Republican Nixon, after all, who created the Environmental Protection Agency and the Council on Environmental Quality, who signed the landmark Clean Air Act into law. Nixon isn't the only Republican President who can claim a green legacy. Environmentalism as a political force effectively began with President Theodore Roosevelt, a lifelong conservationist and outdoorsman who made Yosemite a national park and created 42 million acres of national forests. And even George H.W. Bush, whose promise to be the "environmental President" was about as reliable as his pledge not to raise taxes, signed an update of the Clean Air Act that helped alleviate the dire threat of acid rain.

This isn't to suggest that Democrats and Republicans come in roughly equal shades of green. In the White House and in Congress, the Democratic Party has been a better friend to the environment, especially in recent years. But it means that environmentalism hasn't always been and needn't always be an issue that splits political parties — that valuing the Earth and promoting conservation can be themes that unite Americans, not divide them. And that unity will be especially necessary on climate change, a threat that demands such a sweeping response from America that only truly bipartisan action will get the job done.

The good news is that after nearly eight years of George W. Bush — who will almost certainly own the worst environmental record of any President — conservatives aren't afraid to be seen as green. There's Senator John McCain, of course, the presumptive Republican candidate for President, who was an early leader on climate change in Congress. (Although his idea of lifting the federal gasoline tax for the summer — which Senator Hillary Clinton also supports — is exactly the sort of energy policy we don't need, a pandering fix that will barely affect gas prices and only encourage Americans to drive more.) But there are more unlikely green Republicans as well, like former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who recently starred in an Al Gore–sponsored ad with current Speaker Nancy Pelosi, calling on Americans to set aside their political differences and fight climate change. "You ended up in this space where liberals yelled the word 'environmentalism,' and conservatives always stood on the sidelines saying, 'No,'" says Gingrich. "My view is we ought to be in the middle of this debate." (Listen to Gingrich talk about conservative environmentalism on this week's Greencast.)

Gingrich even published a book last year entitled A Contract with the Earth, calling for a conservative path to dealing with climate change. His solutions differ from those favored by many Democrats and environmentalists, who call for a strong carbon-cap-and-trade program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions over time. Gingrich, true to his GOP roots, advocates private market incentives to encourage the development and dissemination of alternative energy technology, like a $1 billion prize for creating a workable hydrogen-powered car engine. In his view a Kyoto Protocol–style policy will never work, largely because the developing countries like India and China will never sign on to a plan that might hamper their exploding economies. Instead our only hope is to advance low-carbon technologies that are good enough to save the climate and cheap enough for India and China to buy. "If you care about the environment, you have to have a strong interest in science and technology," says Gingrich. "It's not a question of political will. It's a question of whether we can deliver a series of solutions with broad enough support that it's easy for politicians to do it."

Gingrich is right to point out the flaws of the Kyoto Protocol, and to emphasize the need for rapid and drastic technological change. But I think he underplays the degree of government involvement, and the value of a hard carbon cap. If the private market could come up with a workable solution to climate change, well, presumably it would have by now. The reality is that the government will likely need to play a very large role in balancing global warming, and that very fact could turn off conservatives. But for all their talk of small government, most conservatives have long been comfortable with a Washington that is very active in the national security sphere, to say the least — and there's growing evidence that climate change could be as much a security threat as it is an environmental one. Crafting a truly bipartisan approach to global warming won't be easy — but it is necessary, and the fact that people like Gingrich have joined the conversation should give us a little hope.