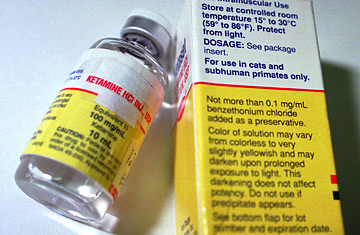

A vial of the animal tranquilizing drug ketamine hydrochloride.

"Oh, Mommy, I like this cartoon world!" From the lips of this perfect little 9-year-old Russian boy, these were welcome words. I was doing something so painful to him yet he was quite comfortable — I was happy to be getting my job done. But soul-chilling doubt attacked as soon as I looked up from his broken arm into the young, innocent, and oh-so-stoned face of my patient.

Sasha was not a normal kid. His parents told me he was a genuine child genius. Spoke three languages, did 12th-grade math, played violin and piano — if you read Orson Scott Card's Ender's Game or saw Little Man Tate, you know the type.

Before I gave him the drugs, I explained to Sasha what was going on, why this fracture through the growth plate in his wrist had to be put back in place right away. I told him that the nerve going to his strangely numb fingers was wrapped tightly around a jagged edge of broken bone, that every minute it stayed there increased the likelihood of permanent damage, maybe a palsied hand. His brilliant dark eyes understood immediately. He understood the time pressure, the risks and why I had to treat him right away, in the emergency room. Sasha nodded and said O.K. Then, so did Mom and Dad. I marveled at how these parents deferred to Sasha's judgment. They knew who he was.

The ER doc with me that night was also exceptional, one of the best there is. She knew a lot about "conscious sedation," that is, knocking patients out just enough to do short emergency procedures without pain or writhing — but also without stopping the patient's heart or lungs. (Emergency rooms are not operating rooms; sedation can be risky, and Sasha had a full stomach, another danger.) But Melissa was her usual cheerful, omnicompetent self: "Don't worry, we can fix up that arm right here. We'll just use a touch of atropine, a little Versed for the nightmares and then the best drug there is for this sort of thing — good old Special K."

Special K, or ketamine, is in fact an old drug. Available since the early '60's, it has enjoyed something of a rebirth in the past few years in hospitals, in-patient psych facilities and — illegally, of course — in nightclubs (the sweaty-techno-mosh-pit kinds, not the ones with elegant ladies at small tables). Though it's listed as one, ketamine is not really an anesthetic; it's not even an analgesic. It doesn't actually stop pain. On Special K, you'll still feel pain — you just won't care. Patients I have seen on ketamine become nonchalant about what's going on with their bodies, as if they're not really in there: "Out of body" is how users say they feel on it.

Many patients, like Sasha, seem to be fascinated by the Special K high. This is what mortified me that night when I realized how much he liked what ketamine was doing to his amazing brain. I was afraid that Sasha had tasted a forbidden fruit, peeked into a place he might never forget, one he might long for. Into a 9-year-old mind already struggling with so much adult turmoil, we had loosed a psychedelic snake proffering an alternative and apparently pleasant reality.

What scared me more was that I had never taken a bite of that apple myself. Put another way: I can describe my wife's chocolate cake. On a good day I could probably write 1,000 words about it. And you could read them all. But unless you had a bite (with coffee) you would never know how good it is. You wouldn't know it like I do. I've never been on ketamine, so I know it only as well as a reader would know my wife's cake — secondhand. I wondered how could I warn Sasha about this drug. Without firsthand experience, could I still reason effectively with him about it? I wondered if there was anyone who could, who could say something like "Look here, son, when I was in fourth grade, reading Crime and Punishment and doing analytic geometry, I tried getting high on ketamine and it seemed great, but let me tell you why it really wasn't"? I held Sasha's arm and watched his face as the plaster cast hardened. He was tripping, staring into the mystical middle distance, breathing deep and easy. Was this the face of the next Timothy Leary or Aldous Huxley? Was it my fault?

"Please don't let this mess him up." Formed silently on my lips.

A different set of eyes turned. We waited.

And then it was over. Boy, was I happy to see that first grimace of pain. The plaster was hard, the X-ray was good and the child prodigy was back. He was still a little groggy from the Versed, but there's a world of difference between the sleepy-drunk effects of that drug (it's in the valium family) and the floating, hallucinating, who-am-I? mystical effects of ketamine. As Sasha returned to normal I tested the nerve to his hand. "Do you feel me touching your fingers now?" I asked.

"Yes, but I won't be able to practice in this cast," he answered, and I knew, at least for the moment, that Sasha's big brain had won it's fight with Special K.

And, yes, he was the model patient when he came to the office for follow-up. He claimed (perhaps a tiny bit evasively) that he didn't have nightmares and that he couldn't recall anything weird about the night we fixed his arm. Versed does cause amnesia — sometimes. But I like to think it was something already in there, more mysterious and far more powerful, that brought Sasha's head back to earth.

Dr. Scott Haig is an Assistant Clinical Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. He has a private practice in the New York City area.