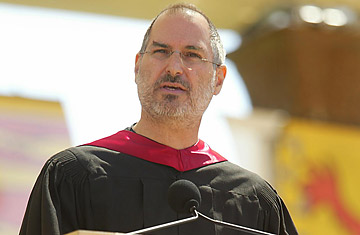

Jobs speaks at the graduation ceremonies at Stanford University on June 12, 2005

(2 of 5)

Woz wanted to build computers to please himself. Jobs wanted to sell them to make money. Their first creation, the Apple I, was mostly a warm-up act for 1977's Apple II. The insides of the II were the product of Woz's technical genius, but much about it — from its emphasis on ease of use to its stylish case design — reflected Jobs' instincts in their earliest form. In an era when most computers still looked like nerdy scientific equipment, it was a consumer electronics device — and a bestseller.

In 1981, Woz crashed his V-tail Beechcraft and spent months recuperating, returning to Apple only nominally thereafter. From then on, Jobs was the Steve who shaped Apple's destiny. In 1979, he visited Xerox's PARC research lab in Palo Alto, Calif., and was dazzled by what he saw there, including an experimental computer with a graphical user interface and a mouse. "Within 10 minutes ... it was clear to me that all computers would work this way someday," he later said.

At Apple, PARC's ideas showed up first in the Lisa, a $10,000 computer that flopped. They then reappeared in improved form in 1984's Macintosh, the creation of a dream team of gifted young software and hardware wizards led by Jobs. Launched with an unforgettable Super Bowl commercial that represented the IBM PC status quo as an Orwellian dystopia, the $2,495 Mac was by far the most advanced personal computer released to date. Jobs said it was "insanely great," a bit of self-praise that became forever associated with him and with Apple, even though he retired that particular phrase soon thereafter.

The Mac was insanely great — but it was also deeply flawed. The original version had a skimpy 128 KB of memory and no expansion slots; computing pioneer Alan Kay, who worked at Apple at the time, ticked off Jobs by calling it "a Honda with a one-gallon gas tank." In a pattern Jobs would repeat frequently in the years to come, he had given people things they didn't know they needed while denying them — at least temporarily — ones they knew they wanted.

Just as Jobs intuitively understood, PARC's ideas would have ended up on every computer whether or not the Mac had ever existed. But there's no question that he accelerated the process through sheer force of will.

"He wanted you to be great, and he wanted you to create something that was great," said computer scientist Larry Tesler, an Apple veteran, in the PBS documentary Triumph of the Nerds. "And he was going to make you do that." Whether Jobs was coaxing breakthroughs out of his employees or selling a new product to consumers, his pitches had a mesmerizing quality. Mac software architect Bud Tribble gave it the name it would be forever known by: the Reality Distortion Field.

Jobs may have been inspiring, but he was also a high-maintenance co-worker. He dismissed people who didn't impress him — and they were legion, inside and outside of Apple — as bozos. He was not a master of deadlines. He tormented hapless job candidates and occasionally cried at work. And he was profoundly autocratic. (Jef Raskin, the originator of the Macintosh project, said Jobs "would have made an excellent King of France.")

Among the people whose buttons he increasingly pushed was Apple's president, John Sculley, the man he had famously berated into joining the company with the question, "Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world?" Frustrated with Jobs' management of the Macintosh division and empowered by the Mac's sluggish sales, Sculley and Apple's board stripped him of all power to make decisions in June 1985. In September, Jobs resigned.

Decades later, the notion of Apple deciding it would be better off without Steve Jobs is as unfathomable as it would have been if Walt Disney Productions had sacked Walt Disney. In 1985, though, plenty of people thought it was a fabulous idea. "I think Apple is making the transition from one phase of its life to the next," an unnamed, overly optimistic Apple employee told InfoWorld magazine. "I don't know that the image of a leader clad in a bow tie, jeans and suspenders would help us survive in the coming years."