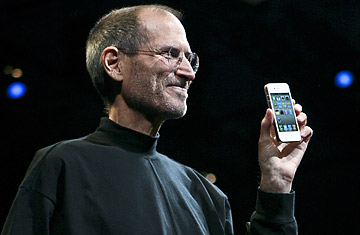

Steve Jobs, introducing the iPhone 4 at a conference in San Francisco on June 7, 2010, resigned as Apple's CEO, but said the company's best days are ahead of it

As stunning developments in the technology industry go, this one happened in a manner that felt inevitable. In yesterday afternoon's crisp, matter-of-fact letter, Steve Jobs told Apple's board and the world that he was unable to continue as the company's chief executive. He asked to serve as chairman, and recommended that Apple COO Tim Cook succeed him as CEO. And he said that Apple's best days were ahead of it and expressed gratitude to his co-workers.

Of course, one hopes that Jobs chose this particular week to step down as CEO not because his health left him no other option but because he felt Apple was ready to move on without his day-to-day involvement. If so, his timing was impeccable. The iPhone and iPad are enormous hits that have left most of Apple's competitors flummoxed; Apple's market capitalization, revenue and profit have all passed those of Microsoft. Simply put, it's this era's pre-eminent technology company.

In a sense, this week's news simply ratifies an existing reality. Since January 2009, Jobs' two medical leaves have curtailed his role for a total of around 13 months. With Cook as acting COO and longtime Jobs associates such as design god Jonathan Ive and marketing honcho Phil Schiller in place, the company has continued to create blockbuster products, generate hoopla and generally thrive.

Thanks to the iPhone and iPad, Apple is extraordinarily well positioned to thrive in the post-PC era, especially if Jobs continues to chime in as chairman. But what happens when a CEO famous for micromanaging every aspect of his company's products officially steps back from managing completely?

It helps that Jobs' vision has been so consistent for so long. In 1976, when the 21-year-old Reed College dropout co-founded Apple Computer with legendary engineer Steve Wozniak and the famous-for-being-forgotten Ron Wayne, the personal-computer industry barely existed. Yet Apple was soon at work on the Apple II, a groundbreaking system that reflected the genius of both Steves. In a period when nobody in the PC business seemed to have even heard of industrial design, Jobs gave the II a custom-designed case that still looks great. And its color graphics and sound capabilities were as dazzling at the time as the iPad is today.

Technologically, the Apple products of 1977, '84, '98 and 2011 are worlds apart. Philosophically, they all reflect the things that matter most to Jobs: simplicity, style, obsessive attention to detail and innovation that delivers tangible benefits. It's an approach that will serve Apple as well in 2025 as it does today.

It also helps that Jobs' legacy isn't only about the ideas he's had; it's about the countless ones he's rejected. Everyone's an expert on what Apple will or should do next, whether it's sensible-sounding (Apple is about to introduce an $800 laptop to compete with dirt-cheap Windows netbooks) or patently silly (Apple is going to buy Adobe, Disney Nintendo, Sony, Twitter and/or Universal Music). Everybody is usually wrong. A huge part of the secret of Jobs' success is the discipline he shows in pursuing only ideas that actually make sense — and it's already pretty obvious that Cook is also a pro at saying no.

Thank heavens that there are people inside Apple who understand how Jobs does what he does, because the rest of us have a lousy track record on the subject. The iPod, the iPhone, the iPad, the Apple Store — all were greeted by people who were only too happy to explain why they were bad ideas that were doomed to flop. (Typical brilliant analysis from a month before the first iPhone's debut: "Why the Apple phone will fail, and fail badly.")

The ongoing inability of folks outside Apple to understand what goes on inside Apple goes a long way toward explaining why no other company much resembles it — and why those who try to mimic its successes (hello, Microsoft Zune!) usually fail. If Jobs hadn't already assembled such a solid executive team, the prospect of a post-Jobs Apple would be scary. There simply aren't any other Silicon Valley executives like Steve Jobs.

The entrepreneur whom Jobs resembles most is another self-made tycoon whose business stood where Jobs has often said Apple's does: at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts. That man was Walt Disney, and he was just as irritable, obsessed and visionary as Jobs. Like Jobs, he built a team of people who had skills he didn't, and then goaded them into creating things — in Disney's case, things such as Snow White and Disneyland — which they would never have come up with on their own.

(Seeing parallels between Jobs and Disney isn't a profound insight on my part. In fact, an unnamed but prescient former Apple staffer quoted in a 1983 TIME story said that Jobs should be running Disney's company — three years before Jobs acquired Lucasfilm's computer-graphics lab and renamed it Pixar, and 23 years before he sold the company to Disney and joined its board.)

The post-Walt history of the Disney company is a sobering example of what can go wrong when an organization's defining leader no longer calls the shots. For years after his death in 1966, Disney's company floundered, subsisting on his leftover projects and rehashed ideas. It kept asking itself, "What would Walt do?" The answers usually involved more family movies and additional theme parks. But if Walt Disney had been running the joint, chances are that he'd have pursued goals that you'd never come up with simply by trying to channel Walt Disney.

As Jobs formally steps back, Apple is faced with a similar challenge. For any specific, immediate issue, answering the question, "What would Steve do?" may be relatively easy — at least if you're as gifted as Apple's key team members are, and have had as much up-close exposure to Jobs as they have. The iPhone 5, iPad 3 and next round of Macs will surely be excellent, influential and successful. So, almost certainly, will multiple generations of these devices to come.

Apple can't just churn out better versions of today's products, though. It needs to figure out what the next big thing is, and to do it better than anyone else. It must ensure that the landmark achievements of Jobs' two tenures at Apple — the Apple II, Mac, iMac, iTunes, Apple Store, iPod, iPhone and iPad — are followed by landmark products in new categories.

If the company succeeds at doing that in the years ahead, it won't be evidence that Jobs turned out to be replaceable. Instead, it'll be proof that he taught the company, which so many fans and detractors believed was a one-man show, to go on being Apple without his intensive involvement. That would be Jobs' final and finest "one more thing" — and right now, the odds seem decent that he'll pull it off.

McCracken blogs about personal technology at Technologizer, which he founded in 2008 after nearly two decades as a tech journalist; on Twitter, he's @harrymccracken. His column, also called Technologizer, appears every Thursday on TIME.com.

Read more about the life and legacy of Steve Jobs in the tribute book from TIME — Steve Jobs: The Genius Who Changed Our World