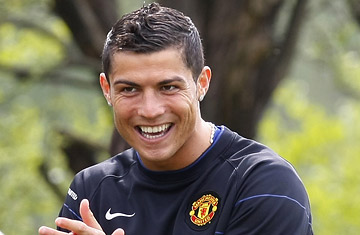

Manchester United's Cristiano Ronaldo during a training session at the club's Carrington training complex in Manchester, northern England

Dazzling moves, ambitious targets and intense pressure — it must be off-season in European soccer. English Premier League champions Manchester United announced today that it accepted a $132 million offer from Real Madrid for fleet-footed winger Cristiano Ronaldo. The deal, which United expects to tie up before the end of the month, would smash a world transfer record set earlier this week when the same Spanish club lavished $92 million on AC Milan's midfield megastar Kaká.

What recession? Defying the downturn, Europe's clubs could well smash the transfer-spending record this close season. English Premier League teams — which, according to Deloitte, spent $280 million on new players during the January transfer window, more than the amount spent in any of Europe's next four biggest leagues — are again in the mood to shop. The benevolence of billionaires helps. London club Chelsea, bankrolled by Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, reportedly bid $74 million on June 9 for Atletico Madrid striker Sergio Aguero. Manchester City, owned by Sheik Mansour bin Zayed al-Nahyan, a member of Abu Dhabi's royal family, is also keen to strengthen its squad. (See pictures of soccer's European championships.)

Crosstown rivals United, meanwhile, flush with the proceeds of Ronaldo's sale, are unlikely to squirrel the cash in the bank. The result? "It may well be the total level of expenditure this summer will break records," says Simon Chadwick, a professor of sport business strategy and marketing at Coventry Business School, but he adds that spending could be "heavily, heavily skewed toward a small number of clubs."

Absent its own benefactor, Real Madrid, the favored club of Spain's establishment, owes its deep pockets to a powerful brand and unrivaled commercial skills. Owned by 80,000 of its supporters, it's the richest soccer club in the world, with revenues of more than $500 million for the 2007-08 season, double the level of seven years ago. Free to negotiate its own broadcast-rights deal — top teams in England or Germany, say, must sell TV rights collectively — Madrid is halfway through a $1.4 billion, seven-year contract with broadcaster Mediapro. (See the 100 best TV shows of all time.)

Locking in long-term revenue is typical in the sports business and crucial to spending during a downturn. Besides the broadcast deal, by far the world's biggest with a single sports club, Madrid has another season left in its three-year shirt-sponsorship contract with online betting company bwin, and kit sponsor Adidas is signed up until 2012. Although commercial revenue dipped as a share of Madrid's takings in 2007-08 — the departure of Englishman David Beckham, who helped increase merchandise profits 137% during his four years with the club, had a lot to do with that — the signing of Ronaldo and Kaká should give it another boost. Research published this week by Weber Shandwick Sport estimates the players to be worth $175 million a season in fresh revenue from increased shirt sales, sponsorship and match-day revenue. (Read "Brand It Like Beckham.")

In theory, top-flight European soccer, with its loyal fan base and long-term contracts, should be shielded from the worst of the recession. Indeed, attendance across the big five European leagues — England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain — rose 2% in the season just finished. And German and English clubs will all enjoy new and improved broadcast deals in the coming two seasons. But that's not to say the downturn doesn't throw up stiff opposition. "Beyond that very affluent, élite core," says Chadwick, "the mood of austerity is still very, very strong."

Just ask English club West Ham United. Asset-management company CB Holding took over the East London club earlier this week, after its Icelandic owner and chairman Bjorgolfur Gudmundsson lost his trousers in the credit crunch. Iceland's Straumur Bank, CB Holding's major shareholder, is itself in the midst of restructuring after being bailed out by the Icelandic government in March. In Spain, once mighty Valencia is effectively controlled these days by local lender Bancaja, its major creditor, after hapless management and a soured stadium-development plan left the club about $725 million in debt. (See pictures of the global financial crisis.)

And even the biggest clubs cannot escape financial pressures completely. KPMG, auditors for the parent company of Premier League runners-up Liverpool, warned in accounts published last week that the firm's need to refinance some $575 million in bank loans — debt stemming from the club's 2007 takeover by American investors — amounted to "a material uncertainty which may cast significant doubt on the group's and parent company's ability to continue as a going concern." A deal to roll over the debt is likely; as a storied and well-supported club, Liverpool generates healthy revenues and profits. But difficulty raising fresh funds has meant plans for a new stadium — promised when Tom Hicks and George Gillett bought the club two years ago — have yet to get off the ground. With the new season two months away, the off-season buying spree at least provides a fun distraction.