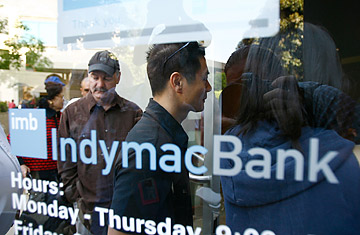

IndyMac will soon earn the first half of its name back. The Federal Government, which seized the failed bank last summer, is expected to close a deal in the next week that would return the California mortgage lender to private ownership. For IndyMac, the deal means independence in less than eight months. For the government, the IndyMac sale provides a shining example of how takeovers can work, at a time when the Obama Administration may soon begin pushing for more nationalizations. (See 25 people to blame for the financial crisis.)

"The fact that the government ownership of IndyMac is coming to an end in just eight months is successful," says Kevin Stein, a former associate director of resolutions at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and an investment banker at FBR Capital Markets. "Nationalization is a tool that has been used in the past and can be effective in the future in certain situations."

A how-to model for nationalizations could prove valuable in the months ahead. The government is in the process of stress-testing the nation's largest banks as part of Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner's plan to fix the ailing banking sector. And many think the outcome of those tests could lead to more takeovers. So far, Geithner and other officials have denied they are interested in running banks. But in the past few weeks, a number of prominent Republicans and fiscal conservatives, most notably former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and Senator Lindsey Graham, have joined those who think the government should consider nationalizing the most troubled institutions. Bank of America, Citigroup and Wells Fargo could all be candidates for increased government ownership and control. (See the top 10 financial-crisis buzzwords.)

To be sure, many economists, and Americans in general, remain firmly against the idea. Some aversion relates to the very word nationalization, which evokes images of socialist regimes seizing private companies. A recent USA Today–Gallup poll found that 57% of Americans are against "temporarily nationalizing U.S. banks." Yet only 44% oppose a less politically threatening version, "temporarily taking [a bank] over."

But the debate involves more than semantics. One concern is that investors aren't going to want to hold any bank shares if the government can simply take ownership, effectively rendering the bank's stock worthless or close to it. An even greater concern is that the government won't be able to resell banks it takes over. That would expose taxpayers to big losses and leave Uncle Sam in the banking business for years to come.

The success of IndyMac, though, shows that the government can accomplish its goal in a relatively short period of time. That's not the only evidence that the feds know how to hustle. Since the beginning of 2008, the government has seized 41 failed banks. In nearly all those cases, the FDIC already had buyers lined up for the failed institutions by the time they were taken over. Troubled banks are generally closed on a Friday and given to new owners over the weekend. In most cases, the failed bank's branches reopen with a new name on the door the following Monday. The one exception is IndyMac, which the FDIC decided to nationalize rather than sell off immediately. (See the worst business deals of 2008.)

Here's how it worked. The FDIC decided to run the bank itself rather than rely on the bank's past managers or hire new ones. So almost immediately after the agency took over IndyMac last July, it sent over two of its top officials, chief operating officer John Bovenzi and Dallas-based assistant director Rick Hoffman, to Pasadena, Calif., to run the bank. Bovenzi became IndyMac's CEO. Hoffman took on the role of president. For Bovenzi and Hoffman, cost-cutting was high on their agenda. They slashed the rate the bank was paying on certificates of deposit. Expensive perks were out as well — the government even sold off the company's Dodgers and Lakers season tickets. A company Porsche fetched $65,000 on Autotrader.com. Also gone are many of the artworks in the elevator lobby and the high-priced office furniture in now empty cubicles.

But the FDIC also has a public-policy mission with IndyMac, which had made many risky mortgages. Many of those loans went to borrowers in California, where home prices have fallen sharply. The FDIC tried to show it could keep many of those borrowers in their homes and still turn the bank around. In all, IndyMac modified the loans of more than 10,000 of its borrowers in less than eight months, in many cases eliminating the chance that those borrowers would face foreclosure. (See pictures of Americans in their homes.)

Despite the government's successes, IndyMac also shows that nationalization can be costly. Last week, the Treasury Department estimated that the IndyMac takeover will end up costing the FDIC nearly $11 billion. Nearly half of those losses came from the actual day-to-day operation of IndyMac, which lost $4.4 billion in the second half of last year.

What's more, IndyMac is only one of four financial firms to have effectively been nationalized during the current financial crisis. Among that group, which also includes Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and AIG, only IndyMac has been returned to private ownership. The others seem a long way off from a similar outcome, if at all. Critics of nationalization say taking over and resolving the issues at a bank like Citigroup, which has hundreds of thousands of employees and businesses spread around the world, would be a much more difficult task than turning around IndyMac, which is a relatively small bank concentrated in the mortgage business.

"IndyMac was a one-trick pony," says Bert Ely, a banking consultant. "Citigroup has a whole stable of horses you have to deal with." Nonetheless, IndyMac does provide an example in which nationalization worked, suggesting that at least some of the fears critics have of nationalization may be unfounded.

"The risk is, you have a nationalized bank that is treated differently by depositors and borrowers because it is owned by the government," says FBR's Stein. "But in the past, that risk has been shown to be manageable."