What a mensch was Peter Falk. An average-Joe hero, he embodied the best of us on our worst day. He was best known as TV's Lieut. Columbo, who, for 30 years, taught snooty murderers that, however crafty they thought they were, he was smarter. Every episode in the series was a class struggle, which reached its peak in the mid-1970's, played as a comedy of manners and won by the wily proletarian. But Falk, who died last night at 83 at his Beverly Hills home after a draining siege of Alzheimer's, was also a significant figure in American cinema. He spanned the gulf between mainstream movies (like The Cheap Detective and The In-Laws) and indie movies (notably those of John Cassavetes) with the ease of a Colossus navigating a mud puddle.

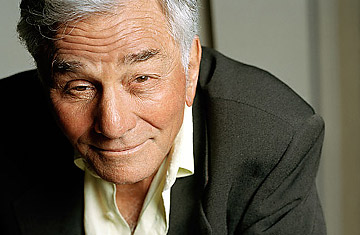

He had one of the great loopy stares in movie history, courtesy of a glass eye that was the trophy from a childhood disease. But Falk's ocular eccentricity would not relegate him to weird comic status; he saw acutely into the human condition of the American male, 20th century, second half. Blessed with a crinkly face that viewers found it hard not to smile back at, Falk would stab the air with his cigar stub as an artist used a paint brush. He played tough guys, gangsters and cops, hundreds of times, managing to show the fraternity of both groups, the humanity of each. A modern folk (or Falk) poet of exasperation, he used a repertoire of eloquent gestures to portrait the weight of the human condition; the slow descending of his shoulders had the grace of Pavlova's dying fall in Swan Lake.

Falk, born in New York City in 1927, didn't let his disability stop him from participating in sports. In a 1997 interview for Cigar Aficionado (a magazine for which the actor could have been every issue's cover boy), he recalled a baseball game in high school: "The umpire called me out at third base when I was sure I was safe. I got so mad I took out my glass eye, handed it to him and said, 'Try this.' I got such a laugh you wouldn't believe." It was an early example of Falk's career trajectory: winning by losing, falling upward.

Rejected by the Army for World War II service, Falk enlisted in the Merchant Marine. Back in the States and bored with college, he tried joining the Irgun, but the war for Israel's independence ended before he could help. By 1953 he had secured a master's in public administration from Syracuse University, and got a Connecticut state job in Hartford, where he started working in theater. Soon he was on Broadway, with a small role in the Phoenix Theatre's 1956 production of Shaw's Saint Joan and, the following year, in an adaptation of Ostrovsky's Diary of a Scoundrel, with Roddy McDowall, Robert Culp and Jerry Stiller.

The forceful patois of his rough-tenor voice must have made an impression in revivals of classical European dramas; but Falk's was a face made for the movies' medium close-up. He got an early starring role in Julian Rothman's Z-minus The Bloody Brood (1959). Playing Nico, a drug dealer masquerading as a beatnik creep, he watches an old man collapse in front of him with a heart attack and lets the man die as a kind of performance art. ("Death is the last great challenge to the creative mind.") He would play variations on that role, minus the preening sadism, for most of the next decade: in the films Pretty Boy Floyd and Murder, Inc. and on TV in The Untouchables. Graduating to gangster parts in A-list movies, he appeared in Frank Capra's Pocketful of Miracles, as the chief bad guy in the Sinatra-Dino-Rat Pack Robin and the 7 Hoods and, finally above the title, as Maximilian Meen in Blake Edwards' The Great Race.