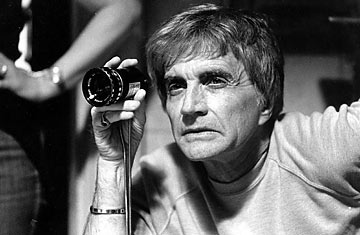

Film maker Blake Edwards on set in 1982.

(3 of 4)

Franchising, a sacred concept in today's Hollywood, was second nature to Edwards. Besides the Pink Panther series, he also turned Peter Gunn into a 1967 feature film, and transformed Victor Victoria into a Broadway musical that ran for two years. But he probably stuck with Clouseau because he wanted to see how many variations he could work on comedy shtick as old as the Greeks. Increasingly stylized into a form of kamikaze Kabuki, the Panther movies exaggerated Clouseau's knack for physical peril: engaging in martial-arts battles with his manservant (Burt Kwok), destroying priceless pianos and violins, walking too near a groin-level rotary fan, burning his hand, then sticking it in an ill-fitting vase or mug. Were the movies funny? Not so much as they were elegant experiments — pure, or strained, essays in the application of pain and humiliation.

Strained, too, was the relationship of Edwards and Sellers, whom Edwards later described as "a monster. He just got bored with the part and became angry, sullen and unprofessional." Yet neither could get out of the Clouseau, even after the actor's death in 1980. Two years later, Edwards presented Trail of the Pink Panther, containing outtakes of Sellers routines. In 1983's Curse of the Pink Panther he floated Ted Wass as a younger Clouseau type, and in 1993 tried to jump-start the franchise by casting Roberto Benigni as Clouseau's half-Italian offspring in Son of the Pink Panther.

The later Sellers-Clouseau films may have been a run-for-cover response for a director whose career had gone south. In the early '70s Edwards had made two movies at MGM: the Western Wild Rovers and the hospital-set comedy mystery The Carey Treatment, from a Michael Crichton novel. James Aubrey, head of CBS TV programming before taking control of the depleted old studio, tangled with Edwards and recut both films — the second one while the director was still shooting it. (When Edwards, in his 2004 Oscar speech, thanked his friends and foes and added, "I couldn't have done it without the foes," he was referring to Aubrey.) Accompanied by new wife Andrews, with whom he had made the musical flop Darling Lili, Edwards retreated to Europe, where he wrote a couple of scripts. He showed the first one to Aubrey, who didn't even finish reading it. Edwards took it back and made it himself. That was "10."

In conception, "10" is a comedy about male voyeurism raised to sexual obsession: George (Dudley Moore), a pop composer who lives, comfortable but restless, with Samantha (Andrews), spots the angelic blond Jenny (Bo Derek) on her way to her wedding, and follows Jenny to her Mexican honeymoon spot, where she asks him, "Did you ever do it to Ravel's 'Bolero'?" In execution, though, the movie was the extension of Pink Panther slapstick. In pursuit of the dream girl, Moore submits to a car crash, getting repeatedly whacked by a telescope, falling off a boat, into a swimming pool and down a mountain slope.

"10" continued Edwards's own preoccupation with the rowdier form of antique film comedy — from the custard-pie marathon in The Great Race (which Sarris said qualifies as "the last spasm of action painting in the Western World") to the Laurel-and-Hardy tribute A Fine Mess, based in part on Stan and Ollie's 1932 short The Music Box. If Edwards had a kindred spirit in late-century cinema, it was not the urbane Billy Wilder but the French master Jacques Tati, whose nearly wordless films (Mon Oncle, Playtime) also replaced surefire jokes with elaborate camera movements, long takes and scenarios of people, machinery — the rickety scaffolding of modern life — collapsing into chaos.