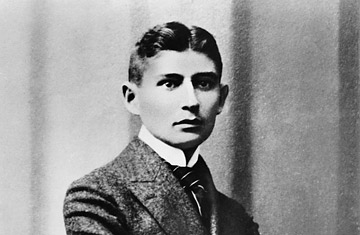

Austrian poet and writer Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

It's not every day that an international dispute of Kafkaesque proportions shakes up the literary world, but one involving the author himself is doing just that.

A protracted legal battle over the contents of four safe-deposit boxes in a Swiss bank, believed by some to contain unpublished works by Franz Kafka or other material shedding light on his life, came to an end on Wednesday when an Israeli judge ruled that the papers should be made public. The decision follows the opening earlier this week of a vault at a UBS bank in Zurich, where the documents were stashed in 2008 by two Israeli sisters who had fought for two years to keep the papers private.

The first box was opened on Wednesday, with reports claiming it contained an unpublished, handwritten story by Kafka. Now scholars are wondering what other literary treasures could be hidden within.

It is known that the man who gave us The Metamorphosis entrusted many of his manuscripts to his friend Max Brod, requesting that they be burned after Kafka's death in 1924. Brod, however, published the novels and took letters and other writings to Israel, where he left them with his secretary Esther Hoffe. For that reason, some experts believe there are no more unpublished or unknown Kafka works waiting to be discovered.

"It's unlikely that any significant manuscripts by Kafka will come to light," says Ritchie Robertson, a professor of German literature at Oxford University and a leading Kafka expert. "But there may be personal papers by Max Brod, such as diaries, which will tell us more about Kafka's life, especially in the years when Kafka was first a student and then starting out on his career as a lawyer and civil servant, which are relatively thinly documented."

Mauro Nervi, an Italian writer and the founder of the Kafka Project, an online forum for scholars and Kafka fans, also believes Brod published everything that was bequeathed to him by his friend. "It is possible, however, that important biographical material about Brod himself and other friends of Kafka will emerge," he says. "And this would be a great event in Kafka research anyway."

However, Kathi Diamant, founder and director of the Kafka Project at San Diego State University and author of Kafka's Last Love, is more enthusiastic about what may be hidden in the Zurich safes. She says she's been waiting "eagerly" for the discovery of unpublished notebooks written by Kafka in the last year of his life, as well as 35 letters he penned to his lover, Dora Diamant (who may or may not be related to Kathi). For nearly a decade after Kafka's death, Dora kept his last writings secret while claiming to have burned them. But after the Nazis confiscated the letters in 1933, she finally confessed her lie to Brod, who made several unsuccessful attempts over the following 20 years to recover the missing documents. Kathi Diamant says the Brod collection contains 70 letters written by Dora to Brod between 1924 and 1952. "I have no idea whether Dora's letters to Brod are in Zurich," she says. "It would be very nice if they were in Switzerland."

Amid the uncertainty, one thing is known: Hoffe, Brod's secretary, left her boss's collection — believed to contain handwritten stories, letters and drawings — to her daughters Eva Hoffe and Ruth Wiesler, who have resisted attempts by Israel's national library to gain custodianship of the papers on the grounds that they represent an important piece of Jewish heritage. (The Prague-born author was Jewish, and while some literary critics claim that Zionism played a major role in his life and his works, nobody has yet demonstrated clear evidence of that theory.)

A two-year legal wrangle ensued, culminating in an Israeli judge's ruling against the sisters and ordering the opening of the Zurich vault, as well as another one in Tel Aviv.

Why did the famously discreet Swiss bank give in to pressure from a foreign government? UBS is not saying, but James Nason, spokesman for the Swiss Banking Association, an umbrella group for Switzerland's financial institutions, says no Swiss bank would respond directly to a foreign court order unless it was transmitted via a Swiss authority. It's unknown why the Swiss court agreed to hand down the order, but Nason adds that, in most cases, banks have no idea what a client has stored in a safe-deposit box.

More details about the contents of the secret archives are likely to emerge in the coming days, revealing just how significant — or not — the documents inside are. But whatever happens next, the legal imbroglio around the safe-deposit boxes, says the Kafka Project's Diamant, "is a nightmare worse than even Kafka would have imagined."