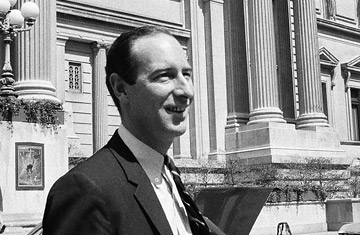

Thomas Hoving in 1967, in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Correction Appended: Dec. 14, 2009

Thomas Hoving held many jobs, but in all of them he played the same role: tireless showman. Over the years, Hoving was a city parks commissioner, a magazine editor, an author and a television correspondent — and to each of those tasks, he brought his superabundant energies, look-at-me narcissism and gleefully roguish manner. But in one job, he left the world a changed place. In his 10 years as director of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, Hoving, who was 78 when he died of cancer on Dec. 10, didn't just transform the Met. He remade the very idea of museums.

What he did was supersize it. The gift shop full of souvenir scarves, the big banners to tout temporary shows, the rentable party spaces — Hoving may not have invented any of them, but he enlarged them all to the proportions we now take for granted. Above all, it was Hoving who did the most to develop the concept of the blockbuster loan show that's now a staple of almost every museum's calendar, to say nothing of its revenue stream. He was the main engine behind the most popular traveling exhibition of all time, the King Tut show. During a three-year tour of seven U.S. cities that ended in 1979, that glittery sampling of Egyptian tomb loot was seen by more than 8 million people, still a record for any single exhibition.

Hoving was born into glitter himself. His father was Walter Hoving, who first headed the swank department store Bonwit Teller and then the luxury retailer Tiffany & Co. The younger Hoving grew up in Manhattan and attended a series of private schools. Then it was on to Princeton, where he got his bachelor's degree, a master's and then a doctorate in art history. In 1958 he went to work for the Met, eventually becoming chief curator of medieval art.

But by 1966, with the Swinging '60s well under way, the museum world was feeling a bit cramped and stodgy to Hoving. That was the year he left the Met to serve as parks commissioner for New York City's newly elected mayor, John V. Lindsay, a dashing liberal Republican (there used to be such things) who was bringing a bit of Kennedy-style panache to the place people would soon be calling Fun City, though usually with tongue in cheek. Hoving fit the new mood perfectly. At the time, the city's parks could be rundown and even sinister, especially at night. Hoving's answer was to bring in crowds and bustle through "Hoving Happenings." He sponsored massive events, like a party for 20,000 children in Central Park's big Sheep Meadow and a public gathering there to watch a meteor shower. "Times have changed," he said. "We're going to open it up and have a little bit of — how shall we call it — Central Park a-go-go."

But just months into Hoving's tenure, he was gone-gone. James J. Rorimer, then director of the Met, abruptly died. After a search that led them to consider more than 40 candidates to succeed him, the Met's ordinarily cautious board of trustees took a chance on the irrepressible and spontaneous Hoving, a man who had told the board members at what you might call his job audition that their museum was "moribund," "gray" and "dying." When he got to his new desk, he was 35, the youngest director in the museum's history, and he walked into the building with all flags flying.

Hoving immediately conceived his first blockbuster, an exhibition of works connected to royal courts, which he gave the unofficial but catchy name Things for Kings. Very soon he negotiated both the acquisition of the ancient Temple of Dendur from Egypt — over the opposition of Jacqueline Kennedy, who wanted it installed in Washington as a memorial to JFK — and the construction of a giant glass-enclosed addition to the museum to house it.

Hoving loved expanding the museum's collections, and he loved the chase. He didn't mind spending lavishly for major works like the Met's great Velázquez portrait of Juan de Pareja, which cost $5.5 million in 1971, a sum that qualified it then as the most expensive painting in the world. He also didn't mind selling off a Van Gogh and a Rousseau to help cover the cost, which got him into a public feud with the press over the notion of museums selling their treasures to buy new ones. The controversy brought on an investigation by the New York state attorney general, who concluded in the end that, if nothing else, no actual wrongdoing was involved in the transactions.

One of his early big shows, however, did almost scuttle his career. As a way to bring African-American audiences into the museum, Hoving decided in 1967 to mount "Harlem on My Mind," a multimedia documentary survey of the history of Harlem, which opened two years later. The very idea offended people who couldn't understand what a historical show was doing at an art museum. That bad reaction got worse when the show's catalog turned out to contain an essay by a young black woman that included anti-Semitic remarks. In the uproar that followed, Hoving nearly lost his job.

In recent years, another episode of his career at the Met came back to haunt him. It involved the Euphronios krater, a Greek mixing pot from the 6th century B.C. that the Met purchased in 1972 for what was then the enormous price of about $1 million. When it was offered to Hoving, he merrily surmised that it might well have been looted from an archeological dig, as he admitted in Making the Mummies Dance, his typically cocky 1993 memoir. Though he goes on in that book to describe how he became convinced that it wasn't stolen, on another page Hoving brags that in his days as the Met's medieval curator, when he made three or four buying trips each year to Europe, "my address book of dealers and private collectors, smugglers and fixers, agents, runners and the peculiar assortment of art hangers-on was longer than anyone else's in the field."

Unfortunately, it turned out the vessel had been looted — from an Etruscan tomb outside Rome — and Italian authorities embarked on a decades-long campaign to get it back. Two years ago, the Met finally packed up "the hot pot," as Hoving liked to call it, and returned it to Italy as part of an agreement under which the museum also returned 20 other disputed items.

Hoving left the Met in 1977 and went on to do a number of things. In the early days of the ABC-TV newsmagazine 20/20, from 1978 to 1983, he was its on-air arts correspondent. For a few years after that, he was chief editor of Connoisseur, a now defunct magazine of the arts, which I contributed to for awhile, so I can say with authority that an editorial meeting with the very tall, tirelessly enthusiastic Hoving was like sitting across a table from a windmill.

And what was his legacy? Did he democratize, glamorize or coarsen the museum experience? You already know the answer. He did all three.

The original version of this article misstated the year Hoving left the Met as 1976. He left in 1977.