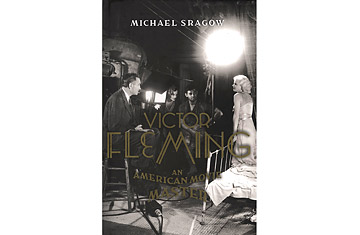

Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master

By Michael Sragow

Pantheon; 645 pages

The Gist:

Scholars tend to lionize directors who develop groundbreaking styles or who come to dominate and define a genre — men like Hitchcock, Welles, Hawks and Ford. But what of the filmmaker who didn't try to stick out so much as fit in; the man-for-hire who could saddle up to any studio assignment — even a work in progress — and mold it to perfection? In Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master, Baltimore Sun film critic Michael Sragow argues that Fleming — who directed The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind — was such a man, denied his rightful place in the cinematic pantheon.

As he jumped between westerns, family films, epic period pieces and goofball buddy pictures, Fleming's rapid climb up the studio ladder came in large part thanks to the friendships he cultivated with such movie stars as Douglas Fairbanks Sr., Clark Gable and Gary Cooper. In particular, his association with Fairbanks got Fleming into the studios, affording the young director not only considerable clout but also an education as to how to tolerate, befriend and mentor major movie stars. It's a skill that was put to good use in working with Judy Garland in Oz and Gable in Gone With the Wind, and Sragow reconstructs the ways Fleming was able to extract defining performances from several A-list actors. While Fleming often deflected the spotlight onto others, here he finally gets his chance to shine. (See TIME's list of the top 10 movies of 2008.)

Highlight Reel:

On Fleming's introduction to MGM, the studio that served as his de facto home: "On October 2, 1931, Fleming received the most important document of his professional life. MGM delivered a letter of agreement for him to direct 'one photoplay' within a seventeen-week period for a salary of $40,000. For most of the 1930s, similar notes would fly back and forth between Victor's lawyers and the studio, because he resisted any long-term contract. Fleming would soon become the MGM director. In 1971, for an oral history project at Columbia University, the producer Pandro S. Berman, who joined MGM in 1940, was asked whether the reputations of MGM's big directors should really have gone on to the producers. 'I would say [so] except in the case of one man ... Victor Fleming was such a powerful man and so strong that he wouldn't do anything until it was his way,' said Berman."

On Fleming's way with talent in The Wizard of Oz: "When [Judy] Garland couldn't stop breaking into giggles at the pseudomenacing advance of [Bert] Lahr's Cowardly Lion, Fleming escorted her off the Yellow Brick Road, said, 'Now darling, this is serious,' slapped her on the cheek, then ordered, 'Now go in there and work.' It must have been one carefully calculated slap from a man with impressive upper-body strength who was also a master of the 'corkscrew punch.' ... Apart from that smack, he stuck to his approach of treating young actors like adults — and the results could be startling."

On Fleming's largely underappreciated work in Gone With the Wind, which he took over from George Cukor halfway through shooting: "Most accounts of Gone With the Wind focus on everything [producer David O.] Selznick did before Fleming arrived ... but rewrites continued during filming, and as [F. Scott] Fitzgerald wrote of Fleming for a 1939 lecture tour by [Sheilah] Graham: '[He was a] fine adaptable mechanism — which in the morning could direct the action of two thousand extras, and in the afternoon decided on the colors of the buttons of Clark Gable's coat and the shadows on Vivien Leigh's neck ... Like all pictures, it had been a community enterprise ... but the tensile strength of this great effort has been furnished by the director.'"

On 1948's Joan of Arc, Fleming's final film and the project that led him to begin an affair with star Ingrid Bergman: "The making of Fleming's last picture, Joan of Arc, becomes one of those behind-the-scenes sagas far more fascinating than the finished film, like the productions of Cleopatra, Apocalypse Now or Heaven's Gate. It would span a decade and a half of creative flirtations, turbulent love affairs, and discordant ambitions ... Even its presentation of Ingrid Bergman as an apple-cheeked warrior-saint — the ultimate tomboy heroine — backfired shortly after the film's release, when the American public condemned her for deserting her husband ... and their daughter." Two days after the film opened, to devastating reviews from Los Angeles critics, "it was Christmas, and Fleming was at his mother's house passing $20 gold pieces to a collection of young relatives and softly admitting to Rodger Swearingen, 'It's a disaster, that picture.'"

The Lowdown:

Not only persuasive in its argument that Victor Fleming was one of the unsung titans of his era, An American Movie Master also makes for a fascinating case study in how power was acquired, wielded and lost during the 1930s and '40s. Fleming knew the score as few did, working his way up the ladder to take control of some of the most ambitious, unwieldy and risky epics in movie history. For readers with a limited knowledge of the movie industry, its transition from silents to talkies, and the rise of the big studio picture, Sragow's thorough scene-setting could double as a cinematic history lesson — illuminating the many famous lives that Fleming touched (and helped to shape) and the ways in which sets, casts, contracts and careers worked during Hollywood's grand glory days.

The Verdict: Read