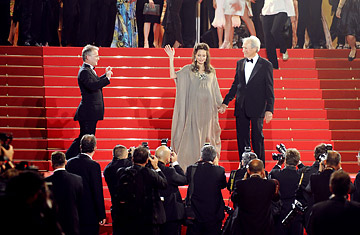

Angelina Jolie and Clint Eastwood meet the press at Cannes

Screenwriter William Goldman's dictum about the movie industry — "Nobody knows anything" — goes double here at Cannes, when it comes to predicting the winners at the closing night ceremony. And it's quadruple this year because none of the 22 films received unanimous critical acclaim, like last year's Romanian winner 4 Months, 3 Weeks & 2 Days. Even the festival's veteran handicappers, like Pierre Rissient and Variety's Todd McCarthy, are loath to lay odds.

Here's what we do know. On Sunday evening, at 7:30 Cannes time, Jury President Sean Penn will start announcing these awards: the Palme d'Or (best picture), a Grand Jury Prize (runner-up), Jury Prize (honorable mention), Best Director (usually a consolation prize), Screenplay, Actor, Actress. Steven Soderbergh's Che is getting Palme d'Or buzz. So is Clint Eastwood,s Changeling. Other films being talked up are the Israeli docu-animation Waltz With Bashir, the French family drama A Christmas Tale and the Belgian The Silence of Lorna, from two-time Palme d'Or laureates Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne.

But it could be none of the above. Or some of the below.

Mothers and Fathers of Italian Ancestry.

Italy, which took consecutive Palmes back in the 1970s (for Padre, Padrone and Tree of the Wooden Clogs) but only one since (The Son's Room in 2001), was back in force this year with two strong films, both of them fact-based melodramas about the deadly reach of organized crime.

Matteo Garrone's Gomorrah is probably the blackest, least sentimental study of the Mafia in Italian or American film history. In its depiction of the Camorra crime family there are no good guys, no crusading cops, no mama pleading with her son to stay out of the rackets. Just ruthless villains and their victims, dispatched without mercy or regret.

The panorama of malefactors includes: a 13 year-old boy who is initiated into the mob by being shot point blank while wearing a bullet-proof vest, something like a Mafia bar mitzvah ("Now you are a man"); a middle-management toughie who, like Tony Soprano, is in the waste removal business (the Camorra holds a monopoly in this industry), dumping drums of toxic sludge; and two punks who quote the Pacino Scarface and think they've hit the jackpot when they stumble on a weapons stash ("Let's rack up corpses," one says, "no use feeling depressed"). Above these scarred, drugged-out creatures are their bosses, wealthy mobsters who remain above the law.

The style of this long, solidly acted film is no more than efficient. What sticks in the mind is the numbing information imparted: that the Camorra is a gangster empire that earned 150 billion Euros just last year; that in addition to dealing in drugs and arms it invests in legitimate businesses around the world, including the reconstruction of the World Trade Center; that in the past three decades the Camorra has murdered more people than al Qaeda. It is these statistics, rather than the movie's ordinary craft, that hold the real power and horror of Gomorrah.

There are criminals and then there are statesmen, and Paolo Sorrentino's Il Divo sees little difference between the two. This is a film of great visual energy about an essentially static figure: Giulio Andreotti, three times the Prime Minister of Italy, a leading light of the Christian Democratic Party, and the star of one of the country's most notorious trials, when he was charged with complicity in the death of the journalist Mino Pecarelli, who had written that Andreotti had Mafia ties and was implicated in the kidnapping and murder of his predecessor as Prime Minister, Aldo Moro. (Andreotti, who has always denied the charges, was in court for years, first acquitted then convicted on appeal before the convictions were annulled by a high court. He spent no time in prison and is now a Senator for life.)

The film's real fascination is with the accoutrements of power: the grand palaces in which policies are made and plots are hatched; the whispered threats and even more ominous silences. The men walk slowly, but Sorrentino's camera moves at a racing glide, turning this talkathon into a thrillingly moving picture. As incarnated by Tony Servillo (who is a front runner for Best Actor and is also in Gomorrah), Andreotti has the stiff posture of Richard Nixon, but a more imperial menace. In this sense, Il Divo has relevance beyond Italy. Its hero-villain could be any leader who stays on the throne by knowing how to dole out lavish rewards and the severest punishments regardless of how brilliant and charismatic he may appear to his supporters.

Surviving Adolescence

Two of the strongest, most poignant films at Cannes deal with young people trying to navigate the labyrinth of adolescence. In most serious international films, especially those from Brazil (Pixote, City of God), the route leads to violence and early death. Linha de Passe, directed by Walter Salles and Daniela Thomspon, renounces the lure of melodrama for a neorealistic study of four sons of a single mother in Sao Paolo. Their have ordinary dreams — to become a football star, to become a religious leader, to be something more than a motorcycle courier, to drive a bus — but they are reluctant to slip into crime or the gang life to achieve it. The mood, which could be brutal, is attentive, admirable, loving. In a quiet way, heroic.

In Brazil as elsewhere, the tragedy of childhood is the absence of a male parent to offer a strong, responsible role model. Linha de Passe shows how the young create their own connections. As Salles notes, when fatherhood is missing, they form a brotherhood.

There is a family of 25 in Laurent Cantet's The Class (Entre les murs): 24 students in a Paris junior high school and their teacher. This affecting, docu-like drama is based on a book by Francois Begaudeau, a former teacher who has the lead role here. His students, a poly-ethnic bunch that includes kids whose parents come from Algeria, Mali and the Caribbean, are encouraged to challenge their teacher, to find ways to speak their most urgent thoughts. This is a French class, but the more important lessons are in self-expression and self-discipline, in learning to live, every day, with other people on society's margins.

Hollywood would take Begaudeau's book and turn it into Blackboard Jungle or Superbad. There are dramas within the class, but Cantet dispenses with melodrama to get to the truths inside these kids and the teacher who gives totally of himself to get through to them. (The kids were discovered in a school in Paris' 20th arrondisement, put through a long workshop period to play characters who were part fictional, part themselves.) As the film unfolds, a half-dozen or more of the children reveal distinct, tough and touching personalities.

It was touching as well to see these young non-actors at Saturday afternoon's triumphant screening of The Class. All conflicts had been resolved as the crowd cheered them, and they cheered their "teacher." For the class of The Class, it was a most moving graduation day. On Sunday, we'll see what honors they receive. They deserve one of the highest.