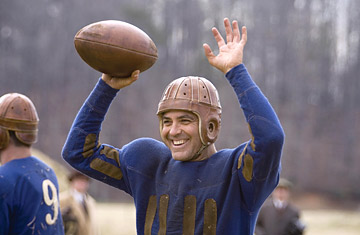

George Clooney in Leatherheads

I never saw the Canton Bulldogs or the Decatur Staleys play professional football. I don't care what anyone thinks; I'm not that old. But I did grow up in Wisconsin, where the last of the small town teams, the Green Bay Packers, claimed my childish heart and, to this day, my aging one. Romantically — and doubtless erroneously — I continue to believe that today's insanely well-paid Packers (representing a franchise worth hundreds of millions) have some near-mystical connection with pro-football's prehistoric days, when, if the players were lucky, they might get fifty or a hundred bucks in return for getting their brains beaten out on Sunday afternoons. To put this matter simply, I can imagine the soulful, sublime and gun-slinging Brett Favre playing for the Duluth Bulldogs.

That's the name of the hard-pressed fictional franchise featured in George Clooney's Leatherheads, in which the director stars as an aging, wise-guy running back named Dodge Connolly, who may have lost a few steps on the field but is yards ahead of most people in sensing pro football's glittering future. That potential is personified by Carter Rutherford (John Krasinski) who has it all: he's a war hero, a snake-hipped runner and cute as all get out. He is a version of Red Grange, who came out of Illinois, signed a huge contract with the Chicago Bears and began the economic and social transformation of the game; the road to the Super Bowl started, however primitively, with Grange.

In Leatherheads, Rutherford is lightly brushed by scandal. And by Lexie Littleton (Renee Zellweger), a proto-feminist newspaper reporter intent on exposing (perhaps inventing would be a better word) a less-than-sterling Rutherford myth. She is, of course, smitten with him. And, she banters fiercely with Connolly — and anyone the least bit familiar with the basic tropes of romantic comedy has to know where that is heading. The course of true love is always charted by the exchange of zingers, which in this case are pretty well written by Duncan Brantley and Rick Reilly.

Indeed, it seems to me the film works better as a comic love story than it does as a sports epic. In its early moments, it features some good, roughneck, on-field shenanigans. The players are simple jocks, content with playing a game of few, loosely enforced rules. But as attention shifts from locker rooms to board rooms, where the real struggle for control of the game's bright, yet much more respectable, future is waged, Leatherheads loses some of its formerly merry ways. It wants to make the case that there is more fun — maybe more simple humanity — to be found in the formative years of mighty enterprises (the movie business is an equally good example), before the sober men in suits take charge. This shift in tone is not entirely fatal to the movie, for Clooney's coolly scheming charm remains intact, and Zellweger gives as good as she gets in their exchanges. I also think that we are witnessing a star-making performance — loose, easy and avoiding the threat of smugness that lurks in his role — from John Krasinski. Maybe the film loses a little steam as it rolls along, but it is still puffing and tooting as Clooney and Zellweger ride off into the sunset — on a comically raffish period motorcycle, free as the wind.