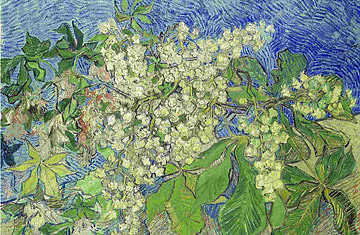

Blossoming Chestnut Branches, painted in 1890 by Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh

Part of the charm of Zurich's E.G. Bührle museum is its quiet residential neighborhood, far from the Swiss city's more crime-infested areas. But the off-the-beaten-track location didn't stop three armed thieves from pulling off what Zurich police called the most "spectacular" theft in Swiss history on Sunday, looting four of the museum's most prized paintings with an estimated value of $160 million.

The brazen heist took place at 4:30 in the afternoon, while 15 visitors strolled around three floors of the vine-covered villa. The masked thieves, including one who witnesses said spoke German with a Slavic accent, ordered the museum staff at gunpoint to lie on the floor. They then stripped the wall of the downstairs salon of four paintings, considered to be among the museum's most expensive, says the museum's curator, Lukas Gloor. The heist took less than three minutes and nobody was hurt.

Among the stolen artworks was Cezanne's The Boy in the Red Vest, one of the favorite paintings of the museum's late founder, Swiss industrialist Emil Georg Bührle. "He considered this work the signature painting of his collection," Gloor, told TIME last year.

Reportedly worth $100 million, The Boy, Gloor said, was part of the "trilogy," of Cezanne's portraits, which also include a self-portrait and a painting of his wife. The three other stolen works are van Gogh's Blossoming Chestnut Branches, Monet's Poppies near Vétheuil, and Degas' Count Lepic and His Daughters.

"The choice of the paintings was probably a combination of premeditation and randomness," Gloor says. "We now believe the thieves targeted the downstairs salon intentionally because that's where our most valuable masterpieces are. But then they randomly picked four paintings that hang in a row."

The museum has offered a reward of $90,000 for information leading to the paintings' recovery, a figure that, Gloor says "is much higher than is customary, but it reflects the value of the paintings and our concern about getting them back safely and quickly."

Switzerland's art community, meanwhile, is wondering whether such a theft could have been prevented in the first place, and if so, how. "The security in our museums is very high," says David Vuillaume, secretary general of the Swiss Museums Association, pointing out that the E.G. Bührle heist was the first armed robbery perpetrated while a museum was open to public. "The question is, how do we protect museums against armed thieves, while remaining open and welcoming to the public?"

Gloor says his museum's security measures are being "looked into." Meanwhile, fearing "copycat thefts," the museum decided to close its doors to the public for an undetermined period of time, though carefully screened and chaperoned group visits can still be arranged.

It is unclear what the robbers will do with their loot. "Obviously, these paintings are too high-profile to sell to art dealers," Vuillaume notes. "We are thinking that maybe in a week or two there will be a ransom demand. But we just have to wait and see."

There is no word on how the E.G. Bührle's management would respond to such an extortion attempt.

In an apparently unrelated incident, two paintings by Pablo Picasso were stolen last week from an exhibition of the artist's works in the nearby Pfaffikon. The Horse's Head and the Glass and Jug, both on loan from the Sprengel Museum in Hanover, Germany, are estimated at several million dollars.

Bührle, who made his fortune selling weapons to Germany during WWII, studied art history and was 30 years old when he began amassing his collection, but his holdings have proven controversial. At least 13 of the artworks he owned at war's end were included on British specialist Douglas Cooper's "looted art list," which was used to recover pieces stolen from Jews by the Nazis. A five-year study undertaken by the Swiss government determined in 2001 that Bührle, who died in 1956, had acquired "flight art" works smuggled out of Axis-controlled areas and sold at rock-bottom prices.

A report on Swiss TV suggested on Sunday that both the Cezanne and Monet paintings were part of the art confiscated by the Nazis, but Gloor denies the allegations, pointing out that Buehrle purchased the works from "longtime collectors."

The theft of the paintings, Gloor says, "is devastating. It's like being a father whose four children are suddenly gone."