Africa has long been renowned for its musical heritage, but it's only comparatively recently that the continent has been exporting it abroad. Youssou N'Dour and the Senegal born hip-hop artist Akon may have broken into the pop mainstream, but both had to conform to Western tastes and styles of music in order to do so. Nuru Kane, the continent's latest musical wunderkind, hopes to change that.

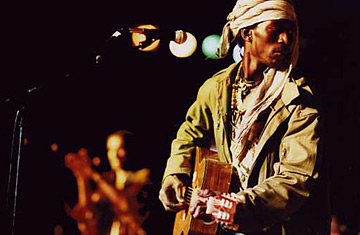

There are a plethora of good singer-songwriters in the west African country of Senegal, many of whom — like Cheihk Lo, Baaba Maal and the peerless N'Dour — have become staples for any self-respecting world music fan in the West. But Kane is different. Less traditional but not quite "Western," he mixes soul and Malian blues with rock tunes on a Moroccan three-stringed guitar known as the guimbri. One London-based music critic described Kane's eclectic sound as "evocative of a kind of pan-Saharan Velvet Underground."

"I take African instruments and play them with [Western] electric instruments." He describes the music as a patchwork, similar to the hodge-podge clothing worn by members of his Baye Fall religion, a Sufi branch of Islam which subsitutes Koranic studies and piety for hard labor. The group's motto dieuf dieul ("you reap what you sow") impels followers to show their devotion to god through work; in Kane's case, through his music.

When Kane sings his tune "Goree," he switches from traditional Senegalese rock n' roll, called mbalax, to Deep South blues, replete with throaty intonations in the style of B.B. King. Goree is an island off the coast of Dakar where slaves were kept before being shipped off to the New World. Nowadays it survives as a popular tourist attraction, particularly for African-Americans looking to retrace their heritage. A contrarian by nature, Kane makes the point that the blues originated in west Africa before crossing the Middle Passage to America.

Kane's first album Sigil, meaning "Wake up" in his local Wolof language, was an underground hit, mixing traditional singing, funk and soul. Kane's next record, due to be released in 2008, is already widely anticipated. But, as the man himself likes to remind listeners in song, fame and success didn't come so easily.

Growing up in a working-class section of Senegal's capital Dakar, Kane listened to European music on the radio and fell in love with the Nigerian Afro-beat pioneer Fela Kuti, whose own music reflected a melee of African and Western styles. As is common in his home country, Kane had trouble finding work. Many young Senegalese dream of making a living abroad, some of whom brave a treacherous journey in the open seas on rickety boats to get to Europe.

Kane's migration was more conventional, but no less difficult. Having moved to France with his wife, he found it hard to acclimatize and struggled to get solid work. Busking in the Paris subways to make ends meet, Kane got his big break when he was spotted by an organizer of Mali's legendary Festival in the Desert. The annual event has attained something of iconic status in the eyes of African music connoisseurs. Set in the dunes of the Sahara, several hours' drive from the nearest town of Timbuktu, the festival attracts an array of world-music talent, both from Africa and beyond. Kane was asked to perform five days before the festival began in 2004 — not even enough time to put his name on the flyers — but his set caused a stir amongst the assembled critics. After being snapped up by a U.K.-based record label, Kane went from the Sahara to the chillier climes of Scotland to record Sigil.

Much of west Africa's rich musical heritage is born out of the "griots" tradition — a caste of wandering musicians who use music to tell oral history, a bit like bards in medieval Europe. Modern-day griots also use rhythm and rhyme to help raise local awareness of issues like HIV-AIDS, a tradition which has been usurped by a new generation of young musicians. "I don't want to just play music, I have a mission to wake up African people," explains Kane.

And unlike in the West where pop music is defined almost purely in terms of its entertainment value, in Africa it's common for even the most popular artists to discuss the continent's weighty social problems in their songs. For Kane, the musical is most definitely the political. "For me it's very important to talk about African problems, we need new leadership," Kane says. "If I'm to be a revolutionary it will not be to kill people — music will be my arms."

Now that Westerners are buying more African music, Kane hopes to weave a new synthesis between East and West. "My aim is to create a new sound," he says. "People have woken up to us, now I want them to open their ears."