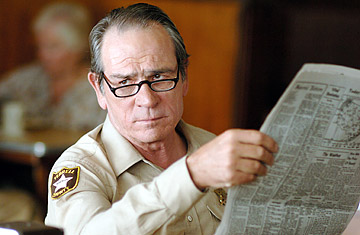

Tommy Lee Jones in No Country for Old Men..

404 Not Found

Before they were seen, the latter two entries were known, according to early rumors, as "the Romanian abortion movie" and "the two-and-a-half-hour Russian film that's worth sitting through." These might not work as advertising catchphrases in Hollywood, but they were accurate, as far as they went. They also undersold two distinguished films that brightened the first days of the Festival.

4 Months, 3 Weeks & 2 Days — a title whose meaning becomes clear only about halfway through the film — is Christian Mungiu's startlingly good drama set in 1987, during the end of Romania's Ceausescu regime. The burdens of Soviet-style dictatorship have imposed a gray pall on the country, putting most of the citizenry in a perpetually sour mood. The black market, for shampoo and Kent cigarettes, is on each street corner, in every college dormitory. That's where we meet Otilia (Annamaria Marinca), a smart, illusionless student, and her pretty, mopey roommate Gabita (Laura Vasiliu). Gabita is despondent for a reason: she's pregnant and is about to try to get, with Otilia's help, an abortion — illegal at the time in Romania.

Through the friend of a friend, Gabita has secured the name of someone who'll do the job: the ironically named Mr. Bebe (Vlad Ivanov). She is afraid of meeting him herself, so she sends Otilia on the errand. Mr. Bebe is an imposing fellow: solidly built and radiating macho menace. Every soft-spoken word and compact gesture announces his threat to these women who need his services. It happens that Gabita has bungled his instructions so completely, by not booking a room in the right hotel and not coming herself for the first meeting, that his rancor is almost justifiable. She has also lied to him about how the extent of her pregnancy, which promotes the operation he's to perform from a punishable offense to a possible murder charge. What price, the girls wonder, will Mr. Bebe charge for the abortion? His answer astonishes and horrifies them.

The movie has a formal rigor familiar to the more serious Cannes entries: virtually every scene, no matter how long, is shot without cutting. That can be an enervating strategy, but here it works marvelously, either forcing the characters together as reluctant conspirators or isolating each in his or her predicament. (There's a bustling scene, at the birthday party of Otilia's boyfriend's mother, that becomes a kind of tour de force, with the gaiety of the celebrants making the girl's misery all the more palpable.) It may be minimalism, but in the best sense: Mungiu has stripped away anything not essential to the story.

That story is tautly, bravely acted, especially by Marinca, an ordinary-looking woman who rivets the camera's attention, and Ivanov, whose bulky poise makes him a figure to fear. More important, the tale is so compelling that it seduces viewers as a fairy tale does a child. They simply must know, as the plot knot coils tighter around the characters, What Happens Next.

But Mungiu also plays games with the audience. As the story unspools he plants three tantalizing details that point it toward a melodramatic climax. Otilia filches a switchblade from the abortionist's case; she learns where Bebe's mother lives; and she comes into possession of his I.D. card, which presumably reveals his address. Will Otilia track Bebe down for the punishment he may deserve? Will all three principals survive their assignation? We're not telling. Suffice to say that what's done with these plot elements is as surprising as the rest of this gripping, satisfying film.

—M.C. and R.C.

Abortion is also an important element in The Banishment. Alex (Konstantin Lavronenko) leaves the city to spend two months in a rural family home with his wife Vera (Maria Bonnevie), their two young children and, from time to time, Alex's small-time criminal brother Mark (Alexander Baluev). Not long into their stay, the brooding Vera shatters Alex with this declaration: "I'm pregnant, and it's not your child." This cues his eventual insistence on an abortion. Their marriage has been strained before, but now the seams split, and anything that can go wrong, does.

There are dire surprises and startling revelations to come, as Alex, Vera and Mark hurtle toward and beyond catastrophe. We will not reveal more of the plot in the hope that one day it will be playing in a theater near you . It is truly something to see; for among all the lives to be ruined it is a visual rhapsody, attentive to every nuance in the spectacular land and foliage around the family home, following the lives within as meticulously as it traces the dramatic changes in weather — from clear day to torrential showers — in one of the longest, most intricate and beautiful tracking shots in cinema.

Beyond the exertions of its storyline, The Banishment pries open, and stares boldly into, the chasm between male and female points of view— questions of love and trust, children and parenting. Men watching the film may find Vera's logic vague and infuriating; women may see her as the sensitive soul, and Alex as the dense husband who only thinks he cares for her. Perhaps Alex and Vera cannot see beyond their own needs. Perhaps no one can. In another movie about lost treasures, Charles Foster Kane offers a toast "to love on my own terms. Those are the only terms anybody ever know — his own."

—M.C.

The Coen brothers have adapted literary works before. Miller's Crossing was a sly, unacknowledged blend of two Dashiell Hammett's tales, Red Harvest and The Glass Key; and O Brother Where Art Thou? transferred The Odyssey to the American south in the 1930s. But No Country for Old Men is their first film taken, pretty straightforwardly, from a prime American novel: Cormac McCarthy's 2005 rumination on the changing ways of crime in West Texas.

The main characters seem to be Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), an ordinary guy who on a hunting trip discovers a lot of money surrounded by a lot of dead bodies, and Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), a tough hombre who wants the money back. "Tough," actually, doesn't do justice to this deadpan psycho whose weapon of choice is a pneumatic air-gun. He's a resourceful creature — when apprehended he uses his handcuffs to strangle a cop — and a memorable sickie.

So, an indelible villain to give you the nightmare creeps, and a kind of hero — the kind the mass movie audience can root for, to get away with a $2 million satchel, and do it against Everest odds. Joel Coen says this is "about as close as we'll ever get to an action movie." On that count, and for most of the film, No Country delivers, with suspense scenes as taut as they are acutely observed. Moss spends most of his sorry time being chased and shot at: as he tries to ford a river pursued by a varmint posse and a killer dog, or jumping out a second-story hotel window with some of Chigurh's ammo in his gut. Joining the chase, of both Moss and Chigurh, are the venerable, philosophizing Sheriff Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) and a wise-ass DEA headhunter (Woody Harrelson). And every bit of this way, I'm admiring and loving it.

The Coens have been accused once or twice of of criminal facetiousness — that their blend of extreme gore and low comedy in such movies as Raising Arizona and Fargo betrays a contempt for both the genre and their characters. If that was ever true, it's not here. No Country has respect for both Moss' can-do resilience and Chigurh's inhuman relentlessness; the film is fascinated with the expertise and poise under pressure of desperate men whose time is running out. For an hour and 40 mins. the film never lets up, deftly charting the itineraries of Moss, Chigurh and Bell as they lurch toward a triangular showdown a a Del Rio motel.

And then... well, not much. Moss vanishes from view, instead of slaking our desire to see him get away free and rich or go down with guns blazing. Chigurh has a unlikely, unsatisfying run-in with coincidence. Most of the screen time goes to Bell: his musings, visits to old friends and recollections of dreams. Jones is always worth watching, but why here? The Coens have lit a fuse they don't let go off. It's as if they junked the natural last reel of the film and substituted it with outtakes for the DVD edition. All this is faithful enough to the McCarthy novel, but not to the demands off the action-film genre the Coens have been flirting with. They not only subvert it, they bury it.

Which is what serious filmmakers do, especially in works shown at festival like this one. As a Cannes critic, I accept their right to undercut expectations; I hereby validate their modernist parking ticket. But there's enough of a movie kid left in me that I'd like to see this almost-great effort not go bust at the end, but climax in a great big bloody BOOM!

—R.C.