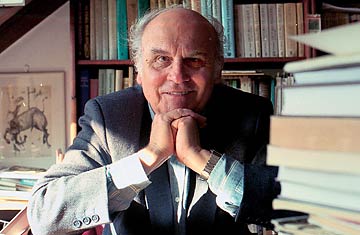

Polish author and journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski poses in his office in Warsaw in 2002.

A little more than a year ago, I was asked to read something at a ceremony for a wonderful man then in the latter stages of cancer. It wasn't a funeral. The man was still alive and would, in fact, attend the ceremony, along with dozens of friends. It was to be a celebration of his life and relationships, bonds he'd formed, not easily, over many years with many people. That he was dying was inescapable, though. Pretending otherwise, when he never did, would have been inappropriate. I chose to read from Jean Giono's The Man Who Planted Trees and The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuscinski, the Polish journalist and author who was for decades the sole third-world correspondent for a Polish news agency. As it happened, I read too long from the former and had to forego the latter, which I regret. The passage I'd selected was the first thing I thought of after reading that Kapuscinski, 74, had died of cancer in Warsaw on Jan. 23.

In the passage, Kapuscinski describes a road trip in East Africa that stalled when the road descended into a massive sinkhole. Cars and trucks had to nose slowly into the chasm then be hauled up the other bank by chain and human hand. Kapuscinski details the setting and the inconvenience, then turns his attention to the men helping the passing vehicles, the women selling drinks or food to waiting drivers, the other little businesses that had sprung up, and the atmosphere of fellowship that had emerged around this abyss.

There are places in the same book where, against his own advice, he generalizes unfortunately about Africa and Africans. There are also some factual errors, and, I'd imagine, places where he aims to articulate a deeper truth rather than give a strictly factual account. But in rendering scenes such as this, he was at his best, depicting the dynamics at work among a group of people in response to capricious circumstance. I also thought it a pitch-perfect description of this man's cancer—a source of misery, without question, but one that drew many people together, if even for an instant, and managed to produce a few moments of joy.

I can't tell you in exactly which country the scene occurred because I don't have the book any more. In fact, I've had to buy several of his books more than once. I read them then give them away, wanting to share them with people close to me. But then I miss them, miss being able to open a copy of, say, Another Day of Life—an account, which I happen to have with me, of the last days of Portuguese rule in Angola—and reading a line like the following, "To this day I don't know why he let me go. He might have been one of those people you meet sometimes who get less of a kick from killing than from knowing they could have killed but didn't."

In his books, he wrote and said things he could not have written or said in a homeland under Soviet control, providing evocative, lyrical descriptions of everyday triumphs and failures. He examined and exposed bravery and cowardice, in others and in himself. He dissected tyrannies large and small, in the high offices where power is held and guarded, and on the street, in the slums, and on the road, where gestures of kindness and casual acts of cruelty constantly occur. To my mind, Another of Day of Life and Shah of Shahs, about the mechanics of the Islamic revolution in Iran, are his finest works. Others might vote for The Emperor, about the court of Ethiopia's longtime dictatorial emperor, Haile Selassie, or The Soccer War, which covers time spent in Africa and South and Central America.

I can't imagine I'll ever forget, in The Shadow of the Sun, an account of sharing space with a furious cobra, or, in Another Day of Life, his lonely admission of dependency on daily telex connections with Warsaw, when he "felt like a wanderer in the desert who catches sight of a spring." And there are lines that resonate today, some of which I found last night flipping randomly through the books I do have here, such as a meditation in The Soccer War on how tyranny enforces life-denying silence on its subjects. But what sticks in my mind most is the passage from Another Day of Life containing both a confession of the shortcomings Kapuscinski saw in his own work and an excoriation of those who sent others into the battles he witnessed: "The world contemplates the great spectacle of combat and death, which is difficult for it to imagine in the end, because the image of war is not communicable—not by the pen, or the voice, or the camera. War is a reality only to those stuck in its bloody, dreadful, filthy insides. To others it is pages in a book, pictures on a screen, nothing more."