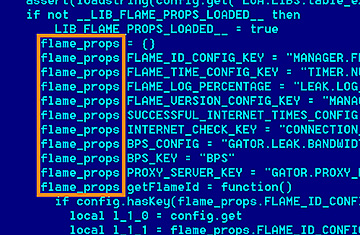

An undated screen grab taken released by the Kaspersky Lab site shows a program of the computer virus known as Flame.

The Iranian technicians went into panic mode late last month as a virus surged through computers at the Ministry of Oil, wiping out hard drives and crashing several websites. One by one, oil terminals in the Persian Gulf were disconnected from the Internet to prevent further damage and a crisis committee was formed to deal with the fallout. By the time the virus had been contained some 24 hours later, computers and websites from the National Iranian Oil Company, the National Gas Company, the Ministry of Oil and several subsidiary companies had taken a hit, according to reports in the Iranian media.

That cyber-attack was downplayed in reports from hardline, government-linked news organizations. But it now appears that the damage could have been done by Flame, a new type of virus that appears even more sophisticated than the Stuxnet worm that wreaked havoc on Iran's nuclear program. In fact, the coding for the Flame virus is roughly 20 times the size of Stuxnet, astonishing many cyber-experts. It has infected more computers in Iran than anywhere else in the world. "This malware can do nearly anything," says Boldizsar Bencsath, a senior analyst at the Laboratory of Cryptography and Systems Security in Budapest, which was one of the first institutions to dissect the virus. "It could be linked to these attacks."

For the Iranian regime, constantly paranoid about external enemies, it's clear that this is another attack in a cyber war that is escalating month by month. Many officials blamed the United States and Israel for the Stuxnet virus and the initial reaction from Tehran appears to point the finger at the same culprits. "It's in the nature of some countries or illegitimate regimes to produce viruses and hurt other countries. We hope that these viruses are knocked out and no one gets hurt," Ramin Mehmanparast, the foreign ministry's spokesman, said at a press conference in Tehran on Tuesday. Israeli officials, for their part, did little to dispel suspicion of their involvement. "For anyone who sees the Iranian threat as significant, it is reasonable that he would take different steps, including these, in order to hobble it," vice prime minister Moshe Yaalon said cryptically on Tuesday.

The Iranian government has long anticipated this digital conflict and has tried to assess both external and internal threats. As part of its readiness for this kind of conflict, Tehran has reportedly spent $1 billion to boost its cyber-defense and offense capabilities in recent months. That has included the purchase of sophisticated monitoring software from ZTE, a Chinese telecom company, as well as filling the ranks of the Iranian Cyber Army with tens of thousands of recruits, according to some officials. The Cyber Army is believed to be linked to the Revolutionary Guard.

The Cyber Army first gained notoriety — and some street cred from hackers — when they took down Twitter in 2009. They have also hacked many Iranian opposition websites and played a lead role in tracking down activists. Last year, the Iranian government also announced the creation of a cyber-police division to help track political dissent online and fight what the regime sees as a "soft war" being waged by anti-regime elements through social media and immoral websites. Just how seriously the government takes the issue was apparent in March when Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei ordered the creation of a Supreme Council of Cyberspace, a governmental body that will include the president, the head of the Revolutionary Guard, the head of the judiciary and the speaker of parliament among other top officials.

Still, it's clear that the Iranian government was unprepared for an attack as sophisticated as the Flame virus. In fact, few other governments could have been. The virus had burrowed into Iranian computer systems at least since 2010 and possibly earlier, sending out data from infected computers. The virus enabled infected computers to take screen shots, turn on attached microphones and record audio, change computer settings, log instant messages and even scan for Bluetooth enabled devices. Among the cyber-experts who have analyzed the virus, there is little doubt that the only group that would have the resources and know-how to deploy such a sophisticated cyber-weapon would be a governmental body. "This was made by some government agency," says Bencsath in Budapest. "The evidence is that it's used for spying on a specific area."

If the Flame virus was created by a governmental agency, it's a risky gambit. The flip side of a cyber-attack is that the virus could be analyzed and repurposed for future attacks. "Unlike a traditional weapon like a bomb, which explodes and disappears, cyber-weapons stay in the system," says Vitaly Kamluk, the chief malware expert for Kaspersky Lab, a Russian IT security company that has done extensive work on the Flame virus. "If someone has the resources to reverse engineer, it can be reprogrammed and used against the enemy. That's a risk."

In a Congressional hearing in late April, a handful of experts testified that Iran is beefing up its cyber-offense capabilities and could be preparing for an attack. The U.S. power grid, in particular, could be a relatively easy target. "What the Iranians lack in capability they make up in intent. Cyber levels the playing field," says Frank Cilluffo, director of the Homeland Security Policy Institute at George Washington University, who testified before Congress during the hearing. "If you look at our own infrastructure, we are quite vulnerable and susceptible."

The Iranian government has been a top suspect in some relatively sophisticated cyber attacks. Last August, a Dutch company called DigiNotar was hacked and a number of SSL certificates, which are used for the encryption of information on the Internet, were stolen. A large number of fraudulent certificates soon appeared on Iranian Internet service providers and were used to track individuals' activities on sites linked to Google and Yahoo among others. This wasn't a cyber smoking gun but it was close: opposition activists suspect that the Iranian government had taken the digital certificates in order to monitor dissident activity in the country. "You can't be 100 percent sure but there's enough circumstantial evidence that it was the Iranian government," says Mehdi Yahyanejad, one of the founders of Balatarin, a community website in Farsi that has become a favorite of the Iranian opposition and has been hacked several times.

Is the Iranian government planning any revenge attacks against the U.S. or Israel for the damage done by Stuxnet or the Flame virus? An editorial that ran last year in the conservative daily Kayhan, whose editor is close to Supreme Leader Khamenei, struck an ominous tone. "Skilled players have appeared who can, in a short period of time, do astonishing and unbelievable damage to American infrastructure," the editorial read. "All they need is a connected computer and knowledge that is no longer under the exclusive control of Western countries." It looks like the cyber-war may be just beginning.