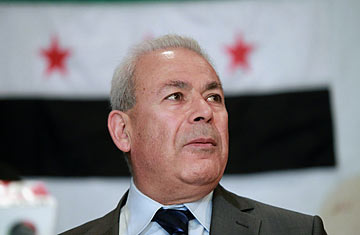

Syria's opposition leader Burhan Ghalioun during a press conference in Cairo on April 24, 2012

The Syrian opposition in exile continue to be intent at sniping at each other as much as at President Bashar Assad. An Arab League initiative to corral the various groups in Cairo in a bid to hammer out their differences collapsed this week when the participants refused to participate. A recent effort by opposition members, both those in the main group, the Syrian National Council (SNC), and those outside it, to restructure the SNC also failed. There was more rancor on Tuesday, when SNC chief Burhan Ghalioun was re-elected for a third time to a three-month post. The issue: the post was supposed to rotate. Many activists were outraged; some said they now had two presidents to depose. On Thursday, Ghalioun offered to resign amid the mounting criticism of his leadership, telling Reuters he would step down "as soon as a replacement is found through elections or consensus."

Ghalioun's move came after the influential Local Coordination Committees (LCC), a key activist network in Syria, threatened to leave the SNC. That action would demolish what little credibility within Syria the SNC, which is largely composed of exiles, still has. In a scathing statement released on Thursday, the LCC lambasted the SNC's structure, its "lack of consensus," its "apparent political deficits" and its "lack of seriousness in dealing with dire issues." Most seriously, it said the SNC had "marginalized the demands of the revolutionaries in Syria" and criticized the extension of Ghalioun's presidency for a third consecutive term "despite his political and organizational failure."

"I told Burhan that there would be a strong reaction if he continues to be president," says Radwan Ziadeh, a prominent Washington-based SNC member. "We should have a new leader to have two things — to restore the credibility of the SNC within the country and at the same time we need a leader who can unify the SNC and to get all of the different groups within it to have one voice."

The LCC criticism is the latest and perhaps most serious challenge to the fractious organization, which has been plagued by infighting and assailed for mismanagement almost since its inception late last summer. Even as its influence expanded internationally, culminating with the Friends of Syria anti-Assad group of nations recognizing it as a (but not the) "legitimate representative of all Syrians," its political capital among grassroots Syrian revolutionaries seemed on a steady downward spiral. Several prominent members resigned.

The question is, What happens now? Will there be a call for fresh elections or will the runner-up of the recent poll, George Sabra, be appointed? SNC spokesperson Bassma Kodmani says that hasn't been decided yet. "The executive committee must meet first," she says. (Kodmani is one of its members.)

The LCC, for their part, were just as scathing toward the executive committee as they were toward its president. Rami Jarrah, a young activist who heads a network out of Cairo, also says grassroots activists are fed up with the SNC's upper echelons. "Even if there was a re-election of the executive council, the executive council itself elected the general council, so it just means that there's no way out of the system they're already in." Jarrah says that opinion among his peers is that the SNC is "just causing trouble." "We've seen nothing but negative coming out of it," he says. "There hasn't been anything positive, so I don't think anyone's going to accept any new formation in the SNC."

Ziadeh says the SNC knows it needs to restructure and that much of the criticism leveled against it is reasonable. "People have high expectations," he says. Ziadeh says the SNC should meet again to discuss a new leader.

Sabra, a longtime dissident who was arrested twice by Syrian authorities in 2011, has been widely considered a successor to Ghalioun. As a Christian, his appointment may also help assuage the concerns of minorities and secularists about the council's perceived Islamist tilt.

Still, it's unclear if the powerful Muslim Brotherhood will accept a Christian leader and if Sabra can and wants to whittle away at the Brotherhood's influence within the council. Jarrah doesn't think Sabra will change much of the organization if he assumes the top job. "He's more a communist than he is a Christian, and they know that," he says. "I don't think he poses a threat to [the Brotherhood]."