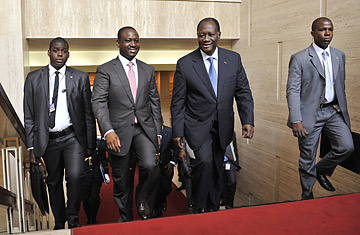

Ivory coast President Alassane Ouattara (2ndR) speaks with Ivory Coast Prime Minister Guillaume Soro (2ndL) after a meeting at Abidjan's presidential palace on March 8, 2012.

When talking about the last 12 months in Ivory Coast's economic capital Abidjan, tailor Ibrahim Diabate's voice quickens. "Look how good the roads are," he exclaims. "There's garbage removal, and more and more people find jobs. Alassane has done more in 10 months than his predecessor did in 10 years," he says, referring to President Alassane Ouattara, who took office last May.

It's a surprising show of support from Diabate. Ouattara is from the north of the country. And like 47% of Ivory Coast's 22 million people, Diabate, a southerner, voted for Ouattara's arch rival, former southern president Laurent Gbagbo in the November 2010 presidential elections. Gbagbo was held to have lost but refused to cede power, sparking six months of violent ethnic conflict in which an estimated 3,000 Ivorians were killed and a million displaced.

After an unusually aggressive United Nations assault against his forces, Gbagbo was arrested on April 11, 2011 and transferred to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, where he faces four charges of crimes against humanity. Today the West African country the size of New Mexico has regained some sense of stability. But although Ouattara is finding approval from some unlikely quarters, an underlying ethnic unease remains. "I don't trust the new president," says Diabete. "The hatred in our hearts remains."

An enduring divide was to be expected. The post-election upheaval was not only brutal — the country saw extrajudicial executions as well as torture, rapes and kidnappings — but also rooted in a decades-long ethnic and regional division. President Ouattara has begun to try to heal the enmity, promising to reform and depoliticize the country's pro-south judicial system and army and set up an inquiry into the violence as well as a South African-style reconciliation commission. Largely peaceful legislative elections in December also led to the formation of a new parliament, which will start work in April. Meanwhile Ouattara's election as chair of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in February marked Ivory Coast's return to the regional stage. Most impressive is how the 60-year-old president, who used to work for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), revitalized the word's biggest cocoa-producing economy in months. The country's gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to grow 8% in 2012 "on stronger-than-expected post-conflict recovery," the IMF announced this month.

But progress in other areas, as well as implementation of some key reforms, has been slow. "Ouattara struggles to reform a political system in which corruption, nepotism and tribalism are deeply engrained," says Sindou Bamba, coordinator of the Ivorian Human Rights Network, which represents 11 non-governmental groups. Reforms to the police and army have also yet to be implemented. U.N. Special representative to Ivory Coast, Bert Koenders, says former enemies must be integrated into one national army and civilians disarmed. "Until then, the country will remain volatile and fragile," he says.

The judicial process also remains compromised. While more than 120 Gbabgo supporters have been prosecuted in military and civil courts, not a single Ouattara backer has been held accountable to date. "So far, Ouattara's promises have been hollow," says Human Rights Watch Ivory Coast expert Matt Wells. Ali Ouattara, no relation and head of the Ivorian Coalition for International Criminal Court Justice, says: "We hope that not only Gbagbo will have to answer to the ICC, but all other key political figures who committed crimes. Otherwise history will repeat itself in Ivory Coast."

Koenders adds Ivory Coast is entering a "crucial year." "Now is the time of reckoning, to see if progress can be consolidated." For now, with that question open, Koenders says it is too early for the U.N.'s 10,500 peacekeepers and police to leave.