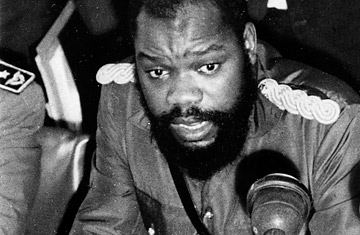

In May 1967, the rebel leader Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu declared the independence of eastern Nigeria, calling it the Republic of Biafra

When, in May 1967, he declared that eastern Nigeria would henceforth be known as the independent Republic of Biafra, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu's intention was simply to break with a northern Nigerian military dictatorship that was violently discriminating against the south and the east. But his action would help set in motion events that led to a civil war in which more than a million people died and presented Africa to a world, already in the television age, as a place of famine and genocide — an image which, to the frustration of a billion Africans, persists to this day.

Ojukwu, who died in London on Nov. 26 at the age of 78, was born in Zungeru, northern Nigeria. His father, transport millionaire Sir Louis Ojukwu, was one of the richest men in Nigeria. Schooled at King's College, Lagos, then Epsom College, in the English town of Surrey, before reading history at Lincoln College, Oxford, the younger Ojukwu returned to Nigeria in 1956 to pursue a career, first in the colonial Eastern Nigeria's administration service, then the army. By 1963 he was commander of the 5th Battalion of the Nigerian army.

In 1966, six years after independence from Britain, Nigeria's military staged a coup led by ethnic Igbo officers from the east. The junta installed Ojukwu as leader of the east. Six months later, a violent northern campaign against the Igbos culminated in a countercoup. The insurgents killed Nigeria's head of state Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, an Igbo, and a northern general, Yakubu Gowon, took power. Ojukwu refused to accept Gowon's regime and on May 30 declared independence for Biafra, a region that included parts of the oil-rich Niger Delta. The announcement was the spark for a civil war that lasted two and a half years. It was an uneven contest. With superior forces and weaponry, Gowon's forces tightened a stranglehold around Biafra, and after a year, the republic had lost half its territory. As part of their siege strategy, the junta also frustrated humanitarian efforts to alleviate suffering, preventing food and supplies from entering Biafra. Pictures of children with distended bellies and stick limbs reached Europe and North America. That prompted the world's first privately organized large-scale relief operation, a campaign in which several leading humanitarians, including the future founder of Médecins Sans Frontières (and future French Foreign Minister) Bernard Kouchner, got their start.

Despite the appalling misery endured by Biafra's population, Ojukwu held fast to the notion of independence, portraying Biafra as a nation threatened by genocide. "The crime of genocide has not only been threatened but fulfilled," he told journalists in 1968. "The only reason any of us are alive today is because we have our rifles. Otherwise the massacre would be complete. It would be suicidal for us to lay down our arms at this stage."

Ojukwu was also a contradiction. He was a well-heeled Oxford-educated man fighting a grassroots rebel campaign. In an August 1968 cover story on him, TIME reported his secessionist views were more a response to popular Igbo opinion than something that arose from personal conviction. Ojukwu was, the magazine wrote, "a calm and reasoned voice pleading for a united Nigeria long after Igbos had arguably given up hope of preserving the union."

By 1969, Biafra was on its knees. Sensing defeat, Ojukwu fled into exile in the Ivory Coast days before Biafra surrendered in January 1970. With the rebellion over, in a moment of pragmatism Gowon declared there had been "no victors and no vanquished." Rebels were quickly reabsorbed into society. Ojukwu was granted a pardon 12 years later and made a triumphant return in 1982. He returned to politics, forming the All Progressives Grand Alliance in 1999, which he led until his death.

Ojukwu's hand in events that helped create a perception of Africa as a place of endless suffering is a mixed legacy. Although the image is humiliating, and increasingly inaccurate, it was that same image that gave birth to the idea of international humanitarian intervention. Inside Nigeria, Ojukwu's legacy is viewed more positively. The Biafra war cast a mold for much of Nigeria's subsequent internal strife. The dynamic of north-south rivalry and authoritarian state vs. secessionist rebel persists to this day in the conflicts between the government and rebels in the Delta and Muslim militants in the northeast. By the stance he took, Ojukwu personified the understanding that Nigeria is often a nation often divided, sometimes violently, by genuine grievance. That insight led President Goodluck Jonathan to pay him an unusually nuanced tribute. Ojukwu's "immense love of his people, justice, equity and fairness," said Jonathan, "forced him into the leading role he played in the Nigerian civil war." For many Nigerians, and certainly for the Igbos, Ojukwu will be cherished as someone who refused to compromise on freedom to an overbearing state. "He will be remembered for many things, top of which is freedom and emancipation of our people," said chief Ralph Uwazurike of the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra. "The Igbo can never forget him for that."