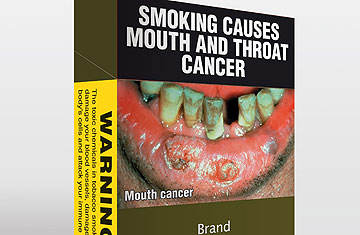

An artist's impression of what cigarette packaging will look like under a new Australian law, due to be implemented by December 2012

A year from now, Australian smokers will have to look a whole lot harder to find their favorite brand of smokes. Thanks to a first-of-its-kind law to be implemented by December 2012, when they glance across the counter they'll be staring at rows of nearly identical, olive green cartons. In place of symbols or slogans, there will be graphic health warnings covering much of each pack.

On Nov. 21, Australia announced that it will be the first country in the world to introduce plain cigarette packaging. It's a controversial move that will be closely watched by countries like Canada, New Zealand and the U.K., all of which are considering similar legislation. Australia already has some of the strictest antismoking laws in the world. Smoking is banned in enclosed public spaces as well as many outdoor areas with laws varying from state to state. Tobacco companies cannot sponsor events in Australia, and cigarettes can only be sold behind closed doors. Still, some 15,000 people die from smoking related illness every year and 15% of Australians smoke. The government wants to reduce that figure to 10% by 2018.

Health campaigners welcomed the decision. "This has been a really important campaign for us," says Ian Olver, the CEO of Cancer Council Australia. "It was one of the last opportunities that the tobacco companies have had to advertise their product." Olver believes the new rules will make smoking less alluring. "Young people get attracted to cigarette packets because of the way they represent their lifestyles. A sportier person might buy what they consider a sportier brand, and every time they take that packet out, they advertise that brand to their peers."

Unsurprisingly, the tobacco industry isn't pleased. Philip Morris, whose brands include Longbeach, Peter Jackson and Marlboro, took action three hours after the legislation passed. Philip Morris Asia Ltd. (PMA), owners of the Australian affiliate Philip Morris Ltd. (PML), served a notice of arbitration on the Australian government. "The Government has passed this legislation despite being unable to demonstrate that it will be effective at reducing smoking and has ignored the widespread concerns raised in Australia and internationally regarding the serious legal issues associated with plain packaging," said Anne Edwards, a PMA spokesperson, in a statement. "Plain packaging turns tobacco products into a commodity, robbing PML of its ability to differentiate its products from competitor brands, and thereby substantially diminishing the value of PMA's investments in Australia."

British American Tobacco Australia (BATA) announced on Nov. 10 that they will take domestic legal action as soon as plain packaging passes into law. "BATA believes it is unconstitutional for the Federal Government to remove a legal company's valuable property without compensation and feels the High Court will agree," said the company's statement.

The government, though, seems confident about the new law, noting that they received "comprehensive" legal advice on the matter. Lawyers agree. Even though it's unconstitutional for the government to acquire property (including intellectual property) without compensation, the government will not actually be taking the trademarks away from cigarette companies. "The government doesn't get to use tobacco trademarks for itself. If it did, it would have to pay," said Simon Evans, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Melbourne, on the Conversation, an academic website.

Marketing experts believe the damage to cigarette brands could be significant. "It will take away any relationship that the consumer has with the brand," says Andrew Hughes, a lecturer at the School of Management, Marketing and International Business at the Australian National University in Canberra. "The consumer won't understand why they would pay more for one type of cigarette and not another. [Tobacco companies] will not go to the effort of making premium products as there's no incentive."

Craig Seitam, a marketing expert who used to work at Rothmans of Pall Mall from 1994 to '98, says that there is not much difference between cigarettes apart from the packaging. "People buy certain brands to project a certain image," he says. "If they have a packet of Dunhill, they might be communicating to others that they see themselves as sophisticated, another brand might say something else, but all that will soon go." But regardless of the change, those who are already addicted are unlikely to quit. "As a social group, smokers have a strong bond," says Hughes, the lecturer. "Because others are smoking, it reinforces your behavior, especially during an office break or outside a bar. That's one thing the government can not do a lot about."