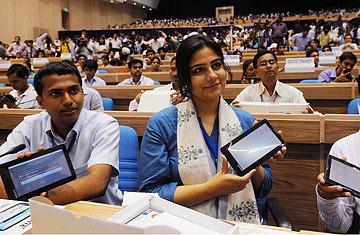

Students in New Delhi show off their new Aakash tablets on Oct. 5, 2011. The $35 device can be used for functions like word processing, Web browsing and video conferencing

India's version of the iPad may have been inspired by Apple's tablet but it costs a fraction of the price. Aakash, or 'sky' in Hindi, was developed by the Indian government as a learning tool and, thanks to a state subsidy, will sell for about $35. After a successful launch, the Indian government and its partner Datawind, a U.K.-based software and hardware company, have their eyes on the U.S., the world's largest consumer-electronics market. But will the discount device actually make it in America?

Although low-cost consumer electronics from Japan, Korea and China have found a ready market in the U.S., Indian innovations have so far witnessed a lukewarm reaction. There has been much interest in the Tata Nano, the world's cheapest car, but its American launch has been delayed until next year. The company is still trying to work its way around the stringent safety requirements in the U.S.

Indeed, American consumers have concerns about the quality of low-cost Indian-made devices, experts say. U.S. consumers are looking for quality assurance, brand names and after-sale service, says Vinit Nijhawan, an entrepreneur and academic based in Boston. New products must also meet the relatively strict requirements of major retailers, he says. "Walmart, Target and Best Buy have rigorous processes for introducing new products to their stores."

"It took a long time for Japanese firms to get their products accepted in the developed world, as it did for the Koreans subsequently," says Harvard's Tarun Khanna, author of Billions of Entrepreneurs: How China and India Are Reshaping Their Futures and Yours. "It is similarly taking time for the Chinese — consider white-goods manufacturer Haier today and various auto and consumer-electronics players from China — and it will take time for the Indians."

The makers of Aakash, though, are confident that they've got sufficient interest from the U.S. — and elsewhere. Suneet Singh Tuli, Datawind's CEO, says he has already received hundreds and thousands of queries, including calls from Latin American mobile operators, a doctor from New York who wants to buy the product to donate to needy New York children, and a retirement home in the U.K. that wants to give its residents a taste of personal computing. "It may not necessarily be the exact same specifications. We have to fine-tune the specifications to be appropriate for that market," Tuli says of the company's strategy. "Even after the tweaks, though, it will be the most aggressively priced, lowest-cost product in the U.S., U.K. markets and elsewhere."

For Aakash, emerging markets will probably be key. The freight cost from India to the U.S. is almost 50% more than freight cost from China to the U.S. This is a major reason why Indian exporters have been moving to Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The demographics also favor developing economies. "There is an emerging middle class in Africa and same in Latin America," says Ajay Sahai, director general of India's top exporters' body, the Federation of Indian Export Organizations. "Indian exporters are more interested in exploring that market."

Indian firms are also increasingly choosing to focus on the home market, says Sahai. The country's rural market makes up 12.2% of the world's population and has 733 million consumers, which is more than twice the population of the U.S. According to a study called Foresight 2020, conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit, India's share in global consumer spending will increase from 1.9% in 2005 to 3.1% in '20. The Nano, after all, was primarily launched to provide a cheap mode of transport for families in rural areas who would otherwise travel on two-wheelers. In 2009, when Nokia's share in India's mobile-phone market fell to 52% (from 64% in 2008), it was attributed to the success of low-cost Indian brands like Micromax, 80% of whose sales come from rural areas.

However, as India's low-cost-product segment matures, there will be companies who would want to cater to traditional markets like the U.S. or the U.K. for a quick profit. "Those companies whose strategies are based on factor-price arbitrage — in this case, cheaper talent in India or cheaper manufacturing in China — are bound to look at the largest markets in the world in dollar terms for their particular products," Khanna, the academic, tells TIME. This will mean changing the perception that "made in India" means low cost and low quality. As Tuli says: "The Indian story going global cannot just be a price story; it needs to be a quality story."