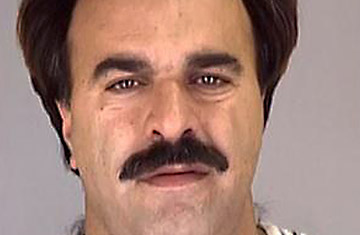

A mugshot obtained October 12, 2011 courtesy of the Nueces County, Texas sheriff's Office shows Manssor Arbabsiar.

In early 2009, after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran's supreme leader declared that anyone killed defending Palestine would be rewarded as a martyr, hundreds of young Iranians descended up Tehran's Mehrabad airport demanding to board flights to meet their deaths. Flummoxed that Khamenei was taken so literally, the government dispatched members of parliament, mullahs, and war veterans to the departure terminal to talk the young people out of this, but the militants refused to budge. The ayatollah himself was finally obliged to issue another edict the following week thanking the youth for their zeal, but ordering them to stay home.

Policy circles in Tehran call this tendency Iran's "problem of the radicals" — essentially the way the country's zealots are imperfectly programmed to behave rashly, at times serving the regime's propaganda aims, but often requiring cooler heads to prevail. It's not just the grassroots militants (private citizens and the volunteer Basij militia) who can veer radically off message. Iran's Revolutionary Guards, whose Quds Force directs the country's activities in places like Gaza, Lebanon, and Iraq, has been split between zealous ideologues and pragmatists for at least a decade. They have often pushed positions more aggressively than the Iranian government itself, and sabotaged official policy. In the years when Iran's government sought to distance itself from the late Ayatollah Khomeini's fatwa against the writer Salman Rushdie, for example, zealots in the ranks of the Guards piped up to note that fatwas couldn't be undone.

Because the Quds force is known for the extremists within its ranks, the question has emerged this week whether its rogue agents might be behind the alleged plot to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the United States. If Quds rogues were at work, they were poorly-equipped to carry out the job. The plot's far-fetched contours, many analysts say, fall squarely outside the pattern of Quds Force activity. With access to unlimited cash and strong ties to regional networks in Iraq, Afghanistan and Lebanon, the Quds Force typically operates through local proxies, leaving few fingerprints behind. One of the last times the United States detailed an indictment of Quds Force activity — in the 1996 bombing of the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia — the evidence against Iran never fully came together. "It is difficult to tell if senior levels of the Iranian government authorized this alleged plot, especially given the potentially grave consequences," says Alireza Nader of the RAND Corporation, referring not only to the already moribund relations with the U.S. but the volatile rivalry with Saudi Arabia in the Gulf.

The sophisticated modus operandi of the Khobar attack is a far cry from the ham-fisted approach documented in the Department of Justice's complaint against Manssor Arbabsiar, which includes a reference to weapons of mass destruction, and is premised chiefly on main suspect's confession. "The indictment reads like nonsense, " says Ali Ansari, an expert on modern Iran at St. Andrew University. "If it's true we're in a lot of trouble, but we need concrete evidence before we can look at this soberly."

The almost confused international reaction to the attacks — including the United States' so far muted response, given the seriousness of the allegations — arises from the lack of sufficient motive on Iran's part. Tehran would seemingly stand to gain little and risk much by launching such attacks on American soil. General Ghassem Suleimani, the chief of the Quds Force, reports directly to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran's supreme leader. Analysts say it is implausible that Suleimani would sign off on a provocative plot that could unleash devastating consequences on Iran. As Nader of RAND puts it, "the Islamic Republic's top leadership is interested in power and survival. Assassinating the Saudi ambassador hurts those objectives."

The debate in Arab and Iranian social media circles suggested that Iran might have been seeking to send Saudi Arabia a signal about Syria, a country roiled by protests in recent months and one where Tehran and Riyadh vie for influence. Iran guards its influence there and in nearby Lebanon jealously. The Saudi ambassador allegedly targeted by the plot, Adel Al-Jubeir, has a history of acting as close intermediary between the Kingdom and Lebanon's Sunni leaders, who Iran views as rivals to its Shi'a ally Hizballah. Information leaked in U.S. diplomatic cables by Wikileaks has only exacerbated Tehran's displeasure with al-Jubeir. The cables quoted Jubeir relaying a message from the Saudi king to top American officials at a Riyadh meeting in 2008: "He told you to cut off the head of the snake."

The changing political dynamics in the Middle East have drastically altered relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia since the days of the Khobar Tower bombings. Back then Washington accused Riyadh of obstructing its investigation to shield Tehran from blame. Furthermore, the status quo in Iraq and the Gulf at the time meant neither country could do very much to jockey for influence. All that changed when the American invasion of Iraq brought that country's Shi'ites to power, and Sunni autocrats throughout the Arab world became vulnerable to popular revolutions. Iran took the upper hand in Lebanon, but Saudi Arabia crushed an uprising by Bahrain's majority Shi'ites, accusing Iran of fueling the unrest.

Neither side has emerged on top in Syria, and Arabs throughout the region have reacted angrily to reports of Iranian forces assisting Syria in suppressing protests. The Tehran-Riyadh rivalry is shaping the new Middle East, but few imagined it would erupt in the Beltway, abetted by a used car salesman from Texas.