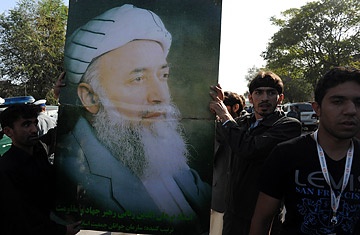

Afghan men carry a picture of Burhanuddin Rabbani, a former President of Afghanistan and the head of the High Peace Council, in Kabul on Sept. 21, 2011, one day after he was killed by a suicide bomber

About 18 months ago, Haji Ismail, an elderly government official in southeastern Afghanistan, received a letter from an old friend. "Whether this peace process, which our elders are discussing with the government, succeeds or fails," it read, "I want to come in." It was signed, with a blue-ink ballpoint pen, by Maulawi Sangeen — one of the Taliban's most dangerous battlefield captains and a deputy to veteran jihadist Jalaluddin Haqqani, whose network is deemed America's most virulent enemy in Afghanistan.

Not only was the erstwhile implacable jihadist seeking peace terms; he was also, if Ismail understood correctly, offering the release of the only U.S. soldier in Taliban captivity as part of the deal. "We have something that belongs to the Americans," the letter said. "It is safe. And we will talk about this as well." The letter was written on a Taliban letterhead and was drafted in a faltering Pashto script. It was political dynamite.

The only problem with Ismail's story is that it was also, according to analysts, an elaborate lie — part of "a long tradition" in Afghanistan of political fakery. "I don't see how you can reach any conclusion other than it's a wheeze by Ismail to persuade someone to give him more money," says Michael Semple, an academic and leading expert on the Taliban. Ismail insists the letter is genuine. "I don't lie," he told TIME. "If I'm lying, then punish me, stone me." But others analysts concur with Semple, arguing that the last thing any senior insurgent trying to defect would do is provide signed evidence of his intentions to a garrulous local official.

Instead, they reckon Ismail was trying to net a share of the $139 million committed by donors to the Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Program (APRP) — his letter materialized shortly after donors announced their pledges at the 2010 London conference. APRP is a high-profile scheme aimed at wooing Taliban insurgents back into the fold. Many observers fear, however, that rather than supporting ex-combatants and their host communities with material help, the larger part of the $139 million will simply disappear into Afghanistan's patronage machine.

Concerns over the state of reconciliation efforts have been amplified by last week's assassination of Burhanuddin Rabbani, the government's designated negotiator with the Taliban. Although his High Peace Council has recorded little tangible progress either in talks with the Taliban leadership or in grassroots efforts to reintegrate the movement's rank-and-file fighters, the running costs for its joint secretariat stood at $2.3 million as of June 30, while a further $1.5 million had gone to APRP cells within government ministries. By contrast, spending on reintegrating former Taliban fighters stood at $150,000.

To some minds, the APRP itself is little more than "a wheeze to channel lots of money to Karzai's allies," as Semple puts it. "And if you're looking for more evidence of this, your Haji Ismail is a pretty good example ... The purpose of this program is not to provide assistance to those who need to have another way of life, another option, another choice. It's a sop to the donors [and] a way of rewarding all those people who are already on the inside and are well connected to those in power — and that's the way the serious Taliban view it."

Cynical as that may sound, it's worth thinking back to previous peace initiatives in Afghanistan. Maulawi Mohammad Sardar Zadran, a former commander who went over to the government in the early days of the Karzai regime, helped run APRP's predecessor, known as PTS. One day, he told TIME, "I received a call from the head of the PTS in Kabul who told me to bring in 30 to 35 Taliban. I said: 'I can't, it takes time, it's not so easy.' They told me to bring in shopkeepers with beards. I told them that was fraudulent [so] they threatened me, said they would cut my salary. [Then] they dismissed me." Across the country, PTS enriched venal officials, did nothing for wannabe defectors from the Taliban and hardened perceptions of the government as corrupt, feckless and insincere. As one Afghan official put it: "PTS was a fiasco."

NATO is adamant that the PTS experience won't be repeated — the APRP program has been designed to prevent the kinds of abuses that plagued its predecessor. "This hasn't been simply a process of tipping money down a pipe and hoping for the best," says Major General Phil Jones, the head of the NATO cell supporting the Afghan government's peace program. "What [the APRP secretariat] has been doing, has been trying to build a unique, decentralized, transparent and accountable system such that money can flow down ... It's been really challenging in the first year when these things weren't in place and yet you want to get on with things ... So yeah, the huge complaint has been that $139 million has sat in the bank here for some time, waiting for disbursement."

It would be nice to think that the meticulous plan sketched out by Jones on a blustery day at NATO HQ in Kabul stands a chance. But amid growing popular skepticism that President Karzai's government and its NATO backers are able or willing to deliver peace, APRP is struggling to get up and running as the political environment becomes increasingly toxic and mistrustful. "Money given by the international community is not getting through," says Thomas Ruttig of the Afghanistan Analysts Network. "I can't say whether that's because they're still taking precautions [against its misuse], but it's almost a year now. Isn't that a little bit long?"

In gloomy guesthouses across Afghanistan, you can find the collateral damage of this slow, deliberate approach. One afternoon in the southeastern city of Khost, TIME stumbles on three brothers pining for their days with the Pakistani Taliban. "Life was good," says Nikzuman, a slight 22-year-old with high cheekbones, an engaging smile and wistfulness beyond his years. "Among the militants we had pickups, weapons, enough money, everything ... But when we reintegrated with the Afghan government, we lost everything." The brothers can't return to the property their parents abandoned during the Soviet invasion of the 1980s for fear their neighbors will sell them out to the Taliban — who have threatened to kill them. So, jobless and outcast, they live on the graces of a family friend. "Other fighters — our former comrades — have called us to ask if the government's providing any resources," Nikzuman explains. "And if so, they say they'll come over. We say: 'Don't bother.' I get a call once or twice a month like that, from commanders of a hundred or 200 men." He pulls his woolen cloak tighter and leans back into the gathering shadows, settling in for the night.