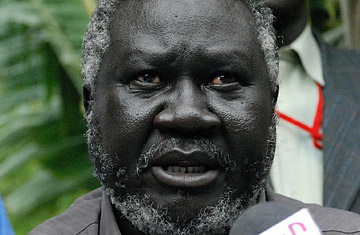

Malik Agar, deputy chairman of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement speaks to the press in the southern Sudanese capital Juba on August 19, 2009.

Clashes erupted in Sudan's Blue Nile state early Friday, making the area the latest and most critical to descend into fighting between the Sudanese government and rebel forces — and bringing the prospect of an all-out Sudanese civil war ever closer to reality. Together with the still unresolved conflict in Darfur and recent war in the Nuba Mountains, the ring of Sudan's rebellions now stretches from the western border with Chad to its eastern border with Ethiopia. Sudan's old civil war appears to be roaring back to life. And chances are, it is only getting started.

The storm clouds had been building for months. Rebel forces in parts of Blue Nile fought as part of the South Sudan rebels, the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM), during the decades-long civil war, but the optimistically-named 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement brokered by the U.S. did little to resolve the area's plight. While the South Sudan leaders of the SPLM who negotiated the peace deal won their homeland its independence, the agreement got their allies across the border in the Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile almost nothing.

The Sudanese military's latest target, judging by the attack on his house on Friday, is Blue Nile's elected governor Malik Agar. (Agar is also the head of the SPLM-North Party and commander of its remaining forces in Blue Nile State.) In the first day of fighting, the Sudanese military quickly grabbed control of the state capital, Damazin, and the Sudanese air force is reportedly already bombing SPLM-held towns. Agar, unharmed, is in the southern part of the state mobilizing his troops; his forces are still heavily armed from his days with South Sudan's SPLM.

When the Nuba Mountains reverted to war in June, the most pressing question in Sudan was: Is Blue Nile next? When I asked Agar that question one month ago in South Sudan's capital, Juba, he didn't explicitly reply in the affirmative, but he gave plenty of cues that he thought so. The heavyset graying general looked tired from trying to balance war-room strategizing with his fruitless shuttle diplomacy aimed at negotiating a ceasefire for his deputy Abdulaziz al-Hilu, who was leading the SPLM's Nuba Mountains fight. Agar predicted Sudan would "disintegrate more." He made sure I had his email address, just in case his phone line stopped working.

It's still not clear who exactly fired the first shot in the new Blue Nile conflict. But both the SPLM in Blue Nile and the Sudanese government in Khartoum had been preparing for this scenario for weeks, and in the past few days the buildup escalated even further, with the two militaries edging physically closer and closer to each other. "It doesn't really matter who started it, it was going to start anyway," says one diplomat closely following the events.

Over the past six years, under the terms of the peace deal, the former rebel Blue Nile and Nuba Mountains SPLM units stayed under the main South Sudan army, which paid for all their salaries and equipment. Now that they are two different countries, South Sudan says it has cut off support to those parts fighting the Sudanese government. Few find that claim entirely credible. If a full war breaks out with its old northern units leading the rebellion against the Sudanese government forces, South Sudan will be forced to make a hard choice: abandon old friends for the sake of neighborly relations with their bitter enemy in Khartoum, or risk a wider war and economic meltdown as it tries to build a nation from a war-ravaged scratch. The South Sudanese leadership in "Juba is divided" over what to do, says the International Crisis Group's Fouad Hikmat.

Sudan's president, Omar al-Bashir can be expected to respond to the rebels in Blue Nile how he generally does: bloodily. Already indicted on several war crimes charges, including genocide at the International Criminal Court, for actions he allegedly took during the conflict in Darfur, he has employed many of the same military tactics in the Nuba Mountains as he did in Darfur: bombing villages and unleashing ethnically-targeted terror in apparent violation of international law.

Pointing to the Western intervention in neighboring Libya, the rebels — who say they want a secular, democratic country and were forced into war by the Khartoum government's aggression and intransigence — are hoping the West sees a parallel in their situation in Sudan. "We are calling for a no-fly zone," says Yasir Arman, the secretary-general of the SPLM-North. But he isn't holding his breath for outside action. "Bashir is wanted by the ICC, and nobody is paying attention to what he is doing," he bemoans, before concluding: "The international community doesn't care about the Sudanese."

So the SPLM-North is making other plans. The rebels have already signed an alliance with Darfur rebel groups, even fighting alongside them in some battles near the Nuba Mountains. With three open rebel fronts, and possibly more on the way, the rebels hope to keep a weakened Bashir — poorer after the loss of the South's oil — on his heels. But to be a serious threat to his rule, they'll need more help: both from the restless youth and opposition parties within Sudan's capital, Khartoum, and from their South Sudanese friends. Whether that happens will determine whether a decade of international diplomacy and billions of aid dollars actually ended a war, or merely created a new sovereign border in the middle of it.