Alleged members of the Knights Templar, a Mexican drug gang, are displayed for the media by federal police on June 22, 2011

At first, the amateur video shows a normal evening in the seething valley town of Apatzingán, in Mexico's western Michoacán state. But as residents and stall owners mix jovially on the sidewalk, the calm is broken by the sinister appearance of masked men gripping machine guns mounted on more than 50 pickup trucks, Hummers and Jeeps. The gangsters cruise openly down Apatzingán's main drag, a frightening show of force even by the brutal standards of Mexico's drug-war bloodbath. The propaganda video was sent to media outlets by the newest players in that conflict, the bizarrely named Caballeros Templarios (Knights Templar). As the name suggests, these narcos are inspired by the Jerusalem-based crusaders who fought in the name of Christ between 1119 and 1312, at which point the Pope disbanded them. But unlike their medieval idols, these thugs cook up methamphetamines, or crystal meth, and have left scores of mutilated corpses strewn about Michoacán since their emergence as a group in March.

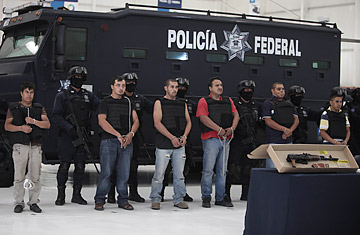

Anyone who follows Mexico's mayhem, which has resulted in almost 40,000 gangland murders since 2007, will find the news of drug-dealing Christian zealots unsettlingly familiar. The Knights are a breakaway group from the "narco-Evangelical" cartel known as La Familia Michoacana, which burst onto the scene in Michoacán five years ago by throwing five severed heads onto a discotheque dance floor. La Familia's criminal and spiritual leader, Nazario Moreno, a.k.a. el Más Loco (the Craziest One), even wrote his own bible of religious ramblings, which was compulsory reading for his troops. Mexican President Felipe Calderón, himself from Michoacán, sent thousands of federal troops to stop the psychopathic gang from unleashing what it called Old Testament justice on everyone from rivals to politicians. In December, federal police allegedly shot Moreno dead; on June 21, police arrested his No. 2, José de Jesús Méndez, whose alias was el Chango (the Monkey). As the Monkey was paraded before reporters on June 22, Mexican police said La Familia had been devastated — a vindication of Calderón's controversial military campaign against the cartels.

But the rise of the Knights Templar from the ashes of La Familia shows the fundamental problem of the drug war: whenever one set of bad guys is taken down, another steps up to take its place, largely because Mexico has few if any real investigative police institutions to halt the vicious cycle. The Knights are purportedly headed by an old lieutenant of Moreno's, Servando Gómez, a former schoolteacher from Michoacán's rugged hills, where meth labs abound like hillbilly stills. Mexican police files show that both Moreno and Gómez converted to Evangelical Christianity when they were migrants in the U.S. in the 1990s. Returning to Mexico, they found that religious discipline was a useful tool to keep criminal troops in line.

Like La Familia, the Knights claim to be pious and patriotic protectors of the Michoacán community even as they traffic and murder. When they first announced themselves last spring, they hung more than 40 narcomanteles, or drug-cartel banners, across the state with a message promising security. "Our commitment is to safeguard order, avoid robberies, kidnapping, extortion, and to shield the state from rival organizations," they said. A week later, their first victim was hanged from an overpass with a note claiming that he was a kidnapper.

But they soon began murdering many of their old friends in La Familia. This points to another key problem in Mexico's drug war: when cartel capos are taken down, their lieutenants battle for the crown. Because former cartel mates are often in the same towns and know where one another's homes are, the internecine fights are particularly devastating. On a single day this month, June 9, thugs displayed 21 rival corpses outside the Michoacán capital, Morelia. Two weeks earlier, fighting between Knights and La Familia loyalists was so fierce that about 1,000 people temporarily fled their villages. The photos of refugees in shelters sent an ominous message about Mexico's security situation (though most returned home after a few days).

The Knights Templar appear to be successfully usurping La Familia's turf. As a result, Mexican army and police commanders have promised to take the new group down with the same energy they summoned to destroy La Familia. But it's unlikely that the Knights will go quietly. In May, their members fired a machine gun at a Mexican federal police helicopter, forcing it to make a controlled landing. Their latest savagery occurred when Mexico opened the under-17 World Soccer Cup in Morelia on June 18. As Mexico's teenagers defeated North Korea, the Knights left 14 corpses on display in nearby villages. "This criminal organization used the event as an opportunity to show off and demonstrate they are here," Michoacán Attorney General Jesús Montejano said.

The massacres have rapidly given the Knights Templar a brutal reputation in an already barbaric conflict, in which drug cartels compete to prove who should be most feared. But one group is miffed about the new gang's name and fame: the official Knights Templar. The International Order of the Knights Templar is an organization of men inspired by the old crusaders to perform charity work. Roberto Molinari, Prior of the Order of the Knights Templar in Mexico, said the cartel's appearance is tarnishing his group's name and putting its members in danger. "The authentic Knights Templar have never had any link to criminal activities," Molinari told Mexican media. "The danger is if the criminals hurt someone and their rivals are looking for revenge, they might find one of our members and shoot them." Molinari wants the Michoacán counterfeits to find another name. And a more Christian crusade.