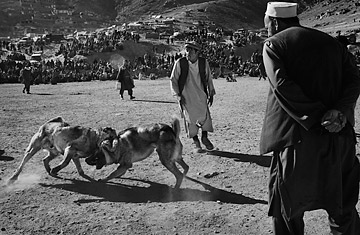

A dogfight in Kabul

Friday is a day of prayer and rest in Afghanistan, but for dogs of a certain size, it's time to fight. On a recent morning, a couple thousand men huddle around a dirt pitch on the outskirts of the capital where hulking mastiffs bare their teeth every week. At center, a green banner is dropped, and two more dogs collide in a cloud of dust. One of them is owned by Tamim Nazir, 24, a restaurant manager whose dog Palang (Tiger) is making his debut. His coat is painted with black stripes, but he doesn't live up to the name. In short order his opponent has locked his jaws around his neck, yanking him to the ground. The match is over. Yet the other dog refuses to let go, and onlookers press in for a closer look. "Get back, you children!" barks a crusty old ringmaster as he whacks them furiously with a stick.

The cold months in Afghanistan see the Taliban-led insurgency die down, but winter is the main fighting season for animals. Large crowds brave the snow to see everything from cocks to camels face off, but dogfighting remains by far the top draw. Banned under the Taliban as un-Islamic, dogfighting has experienced a resurgence around the country, including the restive south, despite militant threats that are sometimes carried through. A February 2008 suicide bombing at a dogfight near Kandahar killed at least 80 men and wounded 90 others. On Feb. 27, 10 more people died when another event in that province was attacked. So why the growing popularity? "We are bored," says Sayed Jan, 22, a shopkeeper and avid fight fan. "People don't really have much to do here on Fridays. It's not like your country."

Although educated Afghans look down on dogfighting as a primitive tradition, there's no enforcement of animal-protection laws to prevent it. If anything, it's a source of street credibility: a brother of Marshal Mohammed Qasim Fahim, Afghanistan's Vice President and a former mujahideen commander, is reputed to maintain a pack of top-notch fighting dogs, including last year's Kabul-area champion, a source of pride to ethnic Tajik dogfighting enthusiasts.

A top fighting dog can sell for as much as a new car and stands to earn many times that from winnings, though few Afghans openly admit to gambling. According to one promoter in Kabul who requested anonymity, the "biggest and best" fights are held in private venues between animals owned by wealthy businessmen and former warlords for purses in the upper five figures — staggering amounts in one of the world's poorest countries. Some owners spend far more to feed and groom their fighting dogs than the typical Afghan will earn in a month.

Given the cost of maintaining fighting dogs and their earning potential, Afghans don't typically fight them to the death as is done in other countries. A bout is over when one dog establishes his dominance or his opponent submits, either by retreating or putting his tail between his legs. Most end within minutes, and little harm is done — and that's how the spectators prefer it. "I don't like it when the dog gets hurt; I want to go home," says Amanullah, 40, a telephone salesman who attends the fights each week. "They cannot talk, so God says we must be kind to them."

Just don't try to pet the dogs. At the earthen amphitheater in Kabul, handlers skid across the ground trying to maintain control of their lunging, barking beasts. Some of the heavier dogs get so riled up, they must be restrained by two men with thick ropes; others are tied to the wheels of cars or soccer goalposts. When one manages to get loose, panicked onlookers flee helter-skelter. "That is a huge embarrassment," says Tamim, watching the owner chase his dog further into the distance. It was the only smile he could muster after Palang's earlier defeat.

Since then, the trainer has stood stone-faced on the edge of the arena with his second dog, Gorg (Wolf), waiting for another fight. Near the end of the competition, his brother returns with good news: a match has been arranged against a younger, undefeated dog of similar size. It's a chance for Tamim to break even, but once again, a fierce flurry of paws and growls ends in defeat. Tamim scoops the bloodied animal in his arms and walks him away from the fray to tend his wounds. "It was a bad day for us," he sighs, "but we'll be back." There's always next Friday to recoup some lost money — he wouldn't say how much — and a touch of pride.