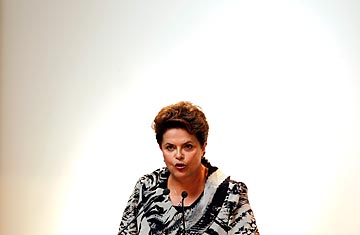

Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff speaks in Buenos Aires on Jan. 31, 2011

Since Brazil's right-wing military dictatorship ended in 1985, the country has enjoyed a string of democratically elected and increasingly progressive administrations. But while neighbors like Chile and Argentina have long since brought to justice many of the worst leaders and henchmen of their own brutal regimes from that era, Brazil has so far declined to seriously investigate the crimes of what many call the "years of lead."

Now, however, more than a quarter-century later, many see hope that the victims of Brazil's 21-year-long tyranny, and the victims' families, might finally be heard. President Dilma Rousseff, the former guerrilla operative who was elected last year, only took office on Jan. 1, but there are early indications that she's prepared to reignite the controversial debate over Brazil's failure to take a deeper — and, many insist, cathartic — look at its sinister past. Rousseff has made pointed references to the years she spent in jail, and she has backed the formation of a truth commission to hear evidence of the abuses, including murder, torture and forced exile, committed by the military government.

Rousseff was emboldened two weeks before her inauguration when the Inter-American Court of Human Rights declared Brazil's amnesty law invalid — and called on the Brazilian government to properly investigate the cases of at least 62 people who disappeared during the country's hapless, short-lived guerrilla war in the early 1970s, something previous governments have refused to do. "The [court] decision challenged the legitimacy and legality of Brazil's amnesty legislation, and that was a very important and historical decision for Brazil," says José Miguel Vivanco, executive director for the Americas at Human Rights Watch. Rousseff "is showing interest and support for the issue of human rights, domestically as well as internationally," adds Vivanco, who feels her popular predecessor, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, too often shied away from the subject. "I have been positively surprised so far."

Brazil's armed forces deposed a sitting President in a March 1964 coup. Though the dictatorship that followed wasn't nearly as cruel or oppressive as those in Chile and Argentina, human-rights groups still estimate that several hundred Brazilian were killed or disappeared during its rule, and thousands more were tortured or forced into exile. Many of the leading lights of what is today Brazil's ruling cohort, the leftist Workers' Party (PT), were among those targeted. Lula was arrested and spent time in jail, and in 1970 Rousseff, then only 23 years old, was tortured and imprisoned for three years on subversion charges.

Lula, however, was strangely unwilling to take his former jailers to task during his eight years (2003-11) in the presidency. He sided with generals who refused to release documents that might help families locate the bodies of missing loved ones, and he backed a Supreme Court decision not to investigate the military's antiguerrilla operations. Nor did he show much stomach for reviewing or even discussing the controversial amnesty law — which was passed during the dictatorship, in 1979, to protect those who might be accused of abuses in the regime's aftermath. (That fact is a big reason the Inter-American Court ruled the amnesty illegitimate.)

Rousseff looks more prepared to confront the elephant in the Brazilian room. In her inaugural address she spoke of the "most extreme adversities inflicted on all of us who dared to stand up to oppression," and her special secretary for human rights, Maria do Rosário, called on the National Congress to pass the truth-commission legislation. Both women warned against turning the effort into a witch hunt against the military, and human-rights activists note that the commission would have no prosecutorial power. But even the suggestion that Brazil look harder at the past has spooked the generals and provoked angry salvos. Rousseff's Defense Minister is adamant that crimes committed by the dictatorship's leftist opponents should receive the same scrutiny as those carried out by the state, and one of her top national-security appointees declared that "the disappeared are the story of our nation [and] we should neither be ashamed nor brag" about them.

As a result, Rousseff knows she has to walk a fine line between investigating past abuses and appeasing the military. (Government officials did not respond to interview requests for this article.) The entrenched protection enjoyed by the military for so long, as well as the general lack of public clamor, means rapid change is unlikely. But for the first time change at least looks possible. "Brazil's political structure hasn't changed and the elite still holds power," says Beatriz Affonso, director of the Center for Justice and International Law, which challenged the amnesty law in the Inter-American Court. "I don't think she will do much just yet, as she doesn't want to cause instability in her first year in office. But I think she will create conditions for it to happen."