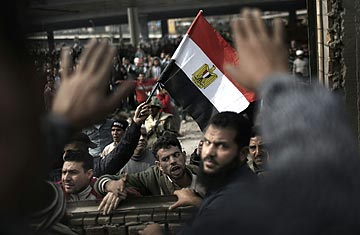

Anti-government demonstrators gather in Tahrir Square, in Cairo, on Feb. 3, 2011

The giddiness that reigned over Cairo last week is gone. On Thursday, Feb. 3, there was a palpable change in the streets of many areas of the capital, including the upper-middle-class neighborhood of Mohandaseen. Most stores in the area remained shuttered. There were long lines at ATMs. Traffic was sparse. A professionally printed banner showing President Hosni Mubarak with the words "yes, yes to the president" hung from a roundabout along the main street.

I was in Mohandaseen on Jan. 28, walking alongside thousands of men, women and children who braved tear gas and police batons to demand democracy. The residents of the multistory buildings lining the main street cheered and clapped, encouraging the protesters below and participating in their witty chants. Later, when the riot police fired tear gas into the crowds, many of these same residents provided water, tissues, vinegar and other supplies to the choking, coughing masses below.

But that was nearly a week ago. On Feb. 1, a massive "march of millions" shook the regime and forced Mubarak to say he would not seek re-election. And on Feb. 2, pro-regime thugs stormed Tahrir Square, the focal point of the peaceful anti-government protests, sparking fierce clashes that continued well into the night and left at least five dead and more than 850 wounded.

On Feb. 3, Mohandaseen, like many parts of Cairo, felt like so many other cowed Arab capitals, frightened into submission. Many people were too afraid to speak. "I'm sorry, I can't talk to you," a 20-something woman who gave her name as Fatima told me. She was at a local supermarket, buying water. "It's too dangerous," she said. "I'm too scared." Scared of what? I asked her. "I don't know who you are. You could be mukhabarat," she said, using the Arabic word for secret police.

Autocratic Arab regimes, especially when embattled, are brutally adept at stoking the currency that underpins their rule: fear. Egypt's is proving to be no different. It's a familiar formula. People can have either freedom or security, but rarely, they are told, can they have both. The marchers wanted freedom. Egypt's government wants a return to the status quo — making it clear that only it can assure security.

State TV has been broadcasting reports that the unrest is the work of Israelis, Palestinian members of Hamas and Lebanese members of Hizballah, among others, conspiracies that have been reinforced in interviews with low-level Mubarak party members. An Arabic SMS message urging people to "kill the foreigners" has also been making the rounds.