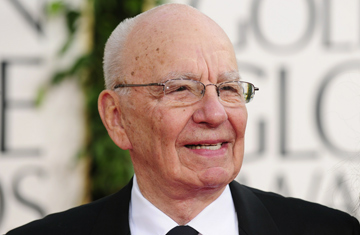

Media tycoon Rupert Murdoch arrives on the red carpet for the 68th annual Golden Globe awards at the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills, California, on January 16, 2011

For an Australian-born U.S. citizen, Rupert Murdoch casts an extraordinarily long shadow over Britain and its politics. As the owner of four U.K. newspapers, he already has a big part in the national conversation. And now his latest bid to take full control of BSkyB, the country's biggest pay-TV station, is giving the government a headache at a time when it's already suffering through expenses scandals, falling poll ratings and public anger over budget cuts. Murdoch announced the $12.5 billion bid last June and already one minister has been stripped of his job of making a ruling on the takeover after he told undercover reporters he had "declared war" on the media tycoon.

As just about anybody in British politics will tell you, declaring war on Rupert Murdoch — the "Dirty Digger," as he has been dubbed by detractors — is not something to be undertaken lightly. This, after all, is the man prime ministers and would-be prime ministers fall over themselves to woo, most notably just before general elections, in the hope of winning the support of his media outlets.

The relationship between Murdoch and Britain's leaders is currently making headlines of its own. Reports on Wednesday revealed that Murdoch had skipped the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland to fly to London while the government considers whether the bid by his News Corporation should be referred to the competition commission. The point at issue is whether, as rival media groups claim, a Murdoch-owned BSkyB — he already owns just over 30% of the company — combined with his existing ownership of four national newspapers — the tabloids the Sun and News of the World, and upmarket the Times of London and Sunday Times — would pose a threat to media plurality in the U.K.

Until Dec. 21, Business Secretary Vince Cable was tasked with deciding if the bid should be sent to the competition commission. But after Daily Telegraph reporters caught him making that combative comment, the responsibility was passed to Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt, who immediately gave Murdoch more time to answer concerns over his bid which had been raised by the media watchdog Ofcom.

For those already concerned about what they see as Murdoch's power over the nation's decision-makers, Hunt's act of leniency appeared to be another sign that politicians are too eager to keep the news mogul on side. And all this comes as controversy continues to boil over the activities of Murdoch's News of the World and phone-hacking of celebrities, royals and politicians by its reporters. That affair saw two employees jailed in 2007, and on Jan. 21, Prime Minister David Cameron's chief spin doctor Andy Coulson, who was the paper's editor at the time of the offenses and says he knew nothing about them, quit as the row refused to die down.

But how is it Murdoch has come to be so feared and revered by Britain's politicians? Probably because some of them have learnt the hard way what his support — or lack of it — can mean.

The most famous example was the struggling Conservative government's shock election victory in 1992, after which Murdoch's Sun newspaper, which had a daily readership of around 10 million, screamed from its front page: "It's the Sun Wot Won It!" Even skeptics were forced to accept that Murdoch's decision to back the beleaguered Tory prime minister, John Major, helped carry the Conservatives to victory.

But it was actually the Sun's treatment of the then opposition Labour party leader, Neil Kinnock, that drew most attention and allowed the paper to make its flamboyant claim. On election day, it had carried a front-page picture of Kinnock's head, portrayed as a lightbulb, under the headline: "If Kinnock wins today, will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights."

Kinnock quit immediately, enraged by his treatment by the media in general and the Sun in particular — and Labour's future Prime Minister, Tony Blair, learned a powerful lesson. In July 1995, Blair and aides jetted to the Australian resort at Hayman Island for an annual conference held by Murdoch and his executives. It was there that Blair persuaded the audience that his "New Labour" Party was responsible and electable. Two years later, the Sun declared for Blair, who went on to win a landslide victory.

Rumors of secret deals between the two men persisted and in February 2009, former Blair-era spin doctor Lance Price seemed to confirm them in his book Where Powers Lies: Prime Ministers v the Media: "A deal had been done, although with nothing in writing. If Murdoch were left to pursue his business interests in peace he would give Labour a fair wind."

In the run-up to last year's general election, that wind seemed to change when the Sun threw its support behind Conservative leader David Cameron. The impact wasn't nearly as striking as it had been years before, thanks to the general decline of newspaper readership and the growth of new media. But it was still a blow to the Labour party, which was ousted from government when Britons took to the polls.

Little wonder, then, that those who fret about Murdoch's power over Britain's politicians are questioning whether Cameron too has decided to leave him to "pursue his business interests in peace."