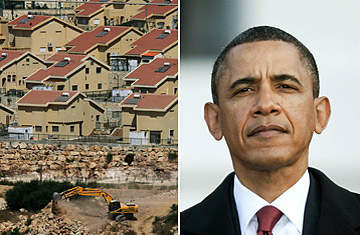

From left: Israeli equipment in the Jewish settlement of Kiryat Netafim, near the West Bank village of Salfit; U.S. President Barack Obama

It was always going to be a struggle for the U.S. to dissuade its Arab allies from going ahead with a U.N. Security Council resolution condemning Israeli settlements. But last week's "people power" rebellion in Tunisia has made Washington's effort to lobby against the plan more difficult. Tunisia has given the autocratic leaders of countries such as Egypt and Jordan more reason to fear their own people. For those regimes, symbolically challenging unconditional U.S. support for Israel is a low-cost gesture that will play well on restive streets.

Going ahead with the resolution, which was discussed on Wednesday at the Security Council and demands an immediate halt to all Israeli settlement construction in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, is, of course, a vote of no-confidence in U.S. peacemaking efforts. And it creates a headache for the Obama Administration over whether to invoke the U.S. veto — as Washington has traditionally done on Council resolutions critical of Israel. The twist this time: the substance of the resolution largely echoes the Administration's own stated positions.

Washington had hoped that signaling its intention to veto such a resolution would force the Palestinians and their Arab backers to hold it back. But they went ahead and placed it on the Council's agenda (a vote is unlikely for a few more weeks), putting the U.S. on the spot. After all, the Obama Administration has demanded that Israel end settlement construction to allow peace talks to go forward. After a 10-month partial moratorium expired last September, Israel resumed vigorous construction, and has resisted pressure from Washington for any further freeze. U.S. Deputy U.N. Ambassador Rosemary DiCarlo said on Wednesday that the U.S. opposed bringing the settlement issue to the Council "because such action moves us no closer to a goal of a negotiated final settlement" and could even undermine progress toward it. But that argument is unlikely to convince most of the international community, given the obvious stalemate in the peace process — there are no negotiations under way, and the Palestinians have refused to restart them until Israel halts its settlement construction. Initial responses at the Security Council reflect unanimous international support for the demand that Israel stop building settlements. If a vote were held today, the U.S. would be the only possible nay.

Long before the Tunisia events, the Arab leaders most invested in the peace process had begun to realize that the strength of Israel's support in U.S. domestic politics had undermined Washington's ability to operate as an evenhanded peace broker. The move to the U.N. has actually been months in the making. That, and the growing chorus of countries in Latin America and elsewhere recently recognizing Palestinian statehood on the 1967 borders reflect a mounting international frustration with a U.S. peace effort whose operating principle has largely been to remain within the bounds of what the Israeli government will accept.

The Security Council resolution is not an alternative to peace negotiations, its sponsors say. In fact, the text urges the parties to resume final-status talks based on existing frameworks, which require a settlement freeze. The Obama Administration has repeatedly described the ongoing settlement construction as illegitimate and an obstacle to peace. The resolution uses the term illegal because existing Security Council resolutions have declared all Israeli construction in the West Bank and East Jerusalem to be in violation of international law. But whether the Obama Administration vetoes a resolution whose contents it is substantially in agreement with may be settled by a domestic political debate.

A bipartisan group of 16 U.S. Senators, led by New York Democrat Kirsten Gillibrand, has urged Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to veto the resolution: "Attempts to use a venue such as the United Nations, which you know has a long history of hostility toward Israel, to deal with just one issue in the negotiations, will not move the two sides closer to a two-state solution, but rather damage the fragile trust between them."

But a number of senior former U.S. diplomats and officials, including former Reagan Defense Secretary Frank Carlucci and former Assistant Secretaries of State Thomas Pickering and James Dobbins, have written to President Obama urging him to support the resolution, which they argue is not incompatible with negotiating an end to the conflict nor a deviation from the U.S. commitment to Israel's security.

"If the proposed resolution is consistent with existing and established U.S. policies," the former officials write, "then deploying a veto would severely undermine U.S. credibility and interests, placing us firmly outside of the international consensus, and further diminishing our ability to mediate this conflict."

Whichever way the U.S. elects to vote on the resolution, the episode is another indication that events in the Middle East are rapidly slipping beyond Washington's control. Whether the evidence is in the formation of an Iraqi government or the collapse of a Lebanese one, it has become palpably obvious to friend and foe alike in the Middle East that the U.S. influence in the region has sharply declined. In fact, Washington could ironically help its Arab allies by wielding the veto to protect Israel from U.N. opprobrium on the issue of settlements — by offering them a low-cost opportunity to grandstand in defiance of the U.S. That won't solve the domestic crises in those countries, but it will play well on Arab streets, where symbolically standing up to the U.S. and Israel is precisely what has made Iran's President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and Turkey's Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, more popular than any Arab leaders are with the Arab public.