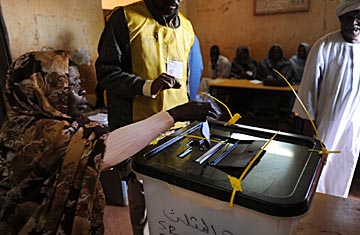

A voter casts her ballot in Al Shegla, Sudan, on Jan. 9, 2011

For Peter Atem, the day southern Sudan sealed its independence could not come soon enough. As midnight arrived in the southern capital of Juba, Atem was already in a queue outside a polling station — even though it would not open until 8 a.m. — so eager was he to vote in a referendum to split his homeland from northern Sudan. After waiting all night, his spirits are undimmed. "Independence is what we have been fighting for," he declares. "We are here to say bye-bye."

For 50 years, the Africans of southern Sudan have struggled against the country's Arab-run central government in the north. The southerners have suffered through war, famine and even slavery in a conflict that is one of the world's costliest: some 2 million Sudanese died in the wars that ran from 1955 to 1972 and from 1983 to 2005. That dark history only made the arrival of Sunday's vote — the culmination of a cease-fire and peace process that both sides agreed to in 2005 — all the brighter. A festive mood reigned in Juba, where young men danced, sang and waved the southern Sudanese flag. But while there is no doubt how the referendum will turn out (it's almost impossible to find support for retaining northern Sudanese rule), many issues still need to be resolved before the south secedes, including how to split the country's oil fields, foreign debt and, most contentious of all, the land itself. Where to draw the line between north and south?

The border is disputed in at least seven places, the most dangerous of which is the town of Abyei, which for years has endured sporadic violence between the two sides. The town was promised its own poll on which side of the border it would be on, but that vote has been postponed due to a dispute over whether Misseriya northern nomads who pass through the area each year should be allowed to vote alongside Abyei's resident Ngok Dinka tribe. Sparks are flying once again.

Fighting between southern police and a Misseriya militia began on Jan. 7 and continued through a third day, multiple sources tell TIME. Nine police officers from the southern side were reported killed during three clashes on Jan. 8, according to a U.N. official, while casualty figures on the northern side were unknown. Clashes continued near the village of Maker Abior on Jan. 9.

The violence appears to stem from well-organized attacks by a Misseriya militia that could number into the hundreds, said the U.N. official, who admitted that the situation was "shrouded in fog." The fighters seem to be targeting the southern police posts that have formed a security cordon around Abyei. Many suspect that the well-armed Abyei police are actually specially trained military soldiers in the southern Sudanese army. Under the peace deal, both sides' militaries had to withdraw outside Abyei's boundaries. Southern officials accuse northern authorities of arming the Misseriya groups.

"Everybody is concerned about Abyei," former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, who is leading a referendum-observation mission, tells TIME while sitting under a tree at one of the many dirt-floored polling stations in Juba. "It's been a flashpoint for the past 15 to 20 years."

Actor and Sudan activist George Clooney, who visited the town on Saturday, assesses the situation more bluntly, telling TIME that if Abyei is not resolved, "then this whole thing falls apart."

Deng Alor, Sudan's former Foreign Minister and the current Minister of Regional Cooperation in the south, is from Abyei, as are a number of other senior political and military officials in the south. "I hope we don't go to war because of Abyei," he says. "But it is definitely part of the process of liberation."

With tension high in Abyei, and with both sides pouring weapons and soldiers into the area, the smallest incident could lead to a wider war. Yet so far, the violence seems contained. Southern officials have vowed to not be provoked into taking action during the referendum. In the north, offers from the U.S. to remove Khartoum from its list of state sponsors of terrorism — as well as focused mediation by the African Union, the European Union and China — appear to have persuaded President Omar Hassan al-Bashir's regime to choose peace, at least outside Abyei.

Which, after so many years of war, is a tantalizing prospect for most southerners. By 10 a.m., Atem has reached the front of the voting line. He relates how the south endured centuries of suppression and colonization — by the Ottomans, the Egyptians, the British and the Arabs. He himself joined the rebels in 1986. After all that time, he asks, what is 10 more hours? "Because now," he says, "we'll be free."