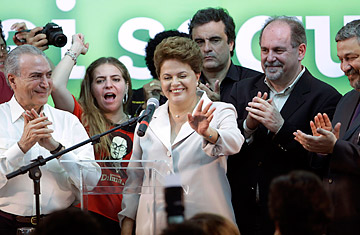

Governing-party candidate Dilma Rousseff, center, was elected Brazil's President, becoming the nation's first female leader, and will take office Jan. 1

Brazil woke up to a new President Monday, Nov. 1, and a guarantee of four more years of the policies of outgoing President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Voters elected his anointed successor, Dilma Rousseff, 62, a former Marxist guerrilla turned civil servant, to become Brazil's first female President.

Rousseff, who, like Lula, is popularly called by one name (Dilma), took 56% of the vote in Sunday's runoff election, easily beating her more centrist rival Jose Serra, who got 44%. The victory was due in large part to Rousseff's close ties to the incumbent and the pair's promise that she would continue many of the policies that sparked Brazil's rise in the global economy and made Lula's eight years in power a huge success.

Lula handpicked his chief of staff to replace him and was at her side throughout the campaign. That support was vital for a career bureaucrat who had served at all levels of government but had never before run for political office and looked uncomfortable alongside her charismatic political patron. Although Lula has suggested that after the presidency — which he could not extend because of term limits — his life might entail anything from running an international agency to drinking beer and watching soccer, Rousseff said as she paid tribute to his work that she would count on his input in the future. "I know that a leader like Lula will never be far from his people and from every one of us," Rousseff said as she choked back tears in her victory speech Sunday night. "I will knock on his door, and I am sure I'll always find it open. The task of succeeding him is difficult and challenging. But I will know how to honor his legacy."

That legacy is recognized by friends and foes alike. Lula kept the nation's economy stable and growing, and he was instrumental in giving Brazil a greater role in international affairs. Most prominently, he made life better for Brazil's poor, and his progressive policies helped close the yawning gap between the haves and have-nots. Rousseff said maintaining and expanding those gains would be her priority, and in an almost carbon copy of Lula's historic acceptance speech eight years ago, she vowed to put the plight of the poor foremost in her calculations. "I reiterate here my fundamental commitment: the eradication of absolute poverty and the creation of opportunities for all Brazilians," she said. "We cannot rest while Brazilians go hungry, while families are living on the streets, while poor children are abandoned."

Her political evolution has been dramatic. The daughter of a Bulgarian immigrant, Rousseff was a teenage economics student when she joined the armed Marxist insurgency fighting the Brazilian military government in the late 1960s, specializing in indoctrinating recruits in communist theory. Captured in 1970, she was tortured — reportedly with beatings and electric shocks — in prison, where she was kept for three years. She says she now believes in what capitalism can do but is equally proud of her past militancy. She joined Lula's government during his first term, in 2003, becoming Energy Minister and then the President's chief of staff, stepping down to campaign to succeed him. Twice married, the President-elect is not currently in a relationship; she has one daughter.

Dilma will take office on Jan. 1, 2011. Passing meaningful legislation will be made easier by her coalition's ample majorities in both houses of parliament. But exactly how she will manage that alliance remains to be seen, as Rousseff — who can give off authoritarian airs — does not have a fraction of Lula's people skills. "It won't be her that does it — she doesn't have the profile to carry that off," says Ricardo Caldas, a political-science professor at the University of Brasília. "If she is as gruff as President [as she was in civil service], it will be a problem for her. She needs a diplomat by her side."

Much like Lula, whose government faced serious corruption scandals, Dilma has had to face questions about her dealings with staff, as well as her campaign's conduct. Members of her Workers' Party were accused of hacking into her opponents' tax returns, and one of her closest advisers was forced to resign after her son was involved in an alleged influence-peddling scheme. Although those issues were prominent in the campaign — and probably prevented her from winning an absolute majority in the first round of voting — they are not expected to hinder her ability to govern.

Also at question is how Dilma will guide Brazil on the international stage. Brazil took on a new global prominence as the B of the so-called developing BRIC nations (the others are Russia, India and China) and was a key player in trade talks, climate-change negotiations and international diplomacy. Lula altered Brazil's long-standing policy of nonintervention and got involved in conflicts in Haiti, Honduras and most controversially Iran.

Dilma has little firsthand foreign policy experience, but she wants Brazil to remain an important player. Her lack of charisma, however, means doors won't swing open for as they did for her predecessor. Some observers say that is not necessarily a bad thing, given Lula's penchant for cozying up to dictators such as the Castro brothers in Cuba and pariahs like President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in Iran. Dilma won't have that same access. But overall policy is unlikely to change, analysts say. "She doesn't understand foreign policy, so she will leave it in the hands of Itamaraty [Brazil's foreign service, named for the building that houses it in the capital, Brasília]," Caldas says. "I don't think the essence will change much."