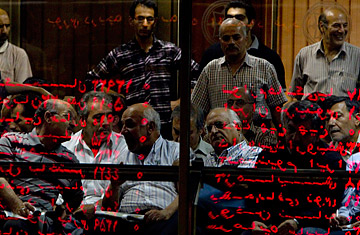

Investors look at an electronic display board, reflected in a glass partition, at the Tehran stock exchange.

Tehran's working classes are clearly worried President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's nebulous plan for reforming the economy. It has raised fears of inflation and unemployment with the likely end of the huge subsidies the government shells out for energy and bread, among others. But Iran's business classes are anxious as well. Farshad, 52, the owner of a company that produces industrial chemicals, wonders aloud whether in the near future he will be paying double or five times as much for the crucial natural gas supply which drives his business. "We cannot see the future clearly. Until now when they have made promises they have not carried them out 100%," Farshad says. "They have said sweet words that are nice to hear, but if things continue to be uncertain I might even stop production. I'm at a loss."

The government has done little to alleviate the worries of industrialists like Farshad. Last Thursday, Finance Minister Shamseddin Hosseini told journalists that answering their questions about the plan would not be "in the interests of the nation." "I request that journalists, despite their curiosity, not expect that we will release all the details of this plan before we implement it," Hosseini said. Top officials have warned that advance information regarding price increases could encourage hoarding and profiteering (in the meantime, however, inflation has, anecdotally, already crept up). The president himself has repeatedly talked about "economic seditionists" who are lying in wait to strike a blow to his government in the name of Iran's enemies. One news website linked to a pro-government member of parliament has even suggested that elements of two banned reformist parties have joined a conspiracy to sabotage the plan.

"One of the keys to this kind of reform is transparency. People need to be able to plan," says Kevan Harris, an Iranian-American sociologist at Johns Hopkins University who has conducted extensive research on Iran's economy and social welfare system, "yet this government does not do that. They actually think the opposite." Harris adds, "They see all this pressure against them and they say that if they give out information they will aid their enemies. It's part of their world view."

Experts say uncertainty surrounding the coming changes has also been one of the factors behind a $6 billion slide in the value of Tehran's stock exchange two weeks ago, with trade volume plummeting 63% and prices dropping 43% in just one week. After a slight recovery, the market fell to new lows again on Tuesday. Before the volatility, the Ahmadinejad administration had for months pointed to the steady increase in stock values as a sign that the Iran's economy was flourishing in the face of sanctions — a dream that appears to be over now amid a climate of doubt and confusion. But many investors had their doubts about the market, feeling it was little more than a bubble enhanced by investors running from stagnation in other investment markets such as real estate.

Business leaders have been openly critical of the government's plans, reacting with disbelief and fear that the government should be considering such a drastic move under the current conditions. "As a result of incorrect policies and the effects of international sanctions, our economy is in crisis," wrote Ramin Sadeghian, a senior official at the Iran Chamber of Commerce, in an editorial in the Khabar Online news website, which is closely linked with Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani who is often seen as a rival of Ahmadinejad. "The supply of cheap energy is the only thing that makes production possible and economical. If the subsidies are removed what advantages are left for our industries?"

The threat of further industrial decline brings with it the specter of increased unemployment. Official figures put Iran's jobless rate at 14.6% but many doubt that this reflects the true figure after a series of revisions by the Ahmadinejad administration expanded the definition of what constitutes actual employment to just one hour of paid work per week.