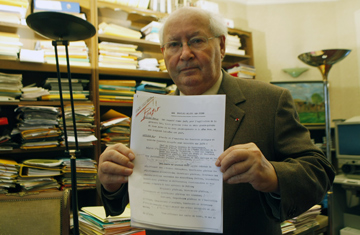

Famed French Holocaust historian Serge Klarsfeld is photographed in his Paris office, Sunday, Oct. 3, 2010, holding a recently uncovered 1940 document.

France's effort to fully examine the dark truths of its Nazi Occupation has gotten another significant boost with the unveiling of a document that exposes the activist role of the Vichy regime in persecuting Jews. The October 1940 draft law shows the personal intervention of Vichy leader Marshal Philippe Pétain in closing a provision that was meant to spare French Jews from restrictions aimed at foreign Jews only. In so doing, the document casts Pétain as instrumental in establishing the broad anti-Semitic policies that two years later facilitated the arrest and deportation of Jews in France to Nazi death camps — and shatters the long-held contention that he sought to protect France from the worst of the Occupation.

The Vichy document titled "Law Regarding the Status of Jews" was unveiled by historian and lawyer Serge Klarsfeld on Oct. 3, just days after it was donated anonymously to the Holocaust Memorial in Paris. Marked "confidential," the typed text is annotated in many places by what experts have authenticated as Pétain's own handwriting. In one critical section that defines the professions and activities Jews were to be banned from, Pétain crossed out the exception for "descendants of Jews born French or naturalized before 1860." That, Klarsfeld tells TIME, proves Pétain was responsible for toughening up repressive legislation and ensuring it would be applicable to all Jews — a role that disproves the dwindling but enduring arguments in France that Pétain actually worked to mitigate the Nazis' anti-Semitic acts as much as possible.

"Apologists have alternatively claimed Pétain did his best to limit the damage during the Occupation, or was just an old man who was manipulated as a figurehead of the Vichy state," says Klarsfeld, who is also president of the Association of Sons and Daughters of French Deportees. "This document shows Pétain not only intervened to push legislation against Jews further than proposed, but created an entire anti-Semitic outlook and framework that — in 1940 — was even harsher than what the Germans had adopted."

The unveiling of the text almost 70 years from the day it became law marks another major step in France's re-examination of its World War II history. Though the preferred analysis for decades viewed France largely as a victim — and resistant — of Nazi Occupation, with only a minority of French people becoming collaborators, efforts to challenge that version of the past began in earnest in July 1995. That was when then President Jacques Chirac broke with long-standing contentions that Vichy was an illegal aberration that did not represent France and apologized to Jews for "the criminal insanity of the occupying power [that] was assisted by the French state."

Chirac's address came during a memorial service at a site in Paris that had been used to detain Jews who had been rounded up by French police for deportation to concentration camps. Since then, France has created official administrations to oversee the return of real estate, artwork, and myriad possessions stolen from Jews during the Occupation. Last year, in an attempt to help with the process of paying damage claims to victims, France recognized the wartime state's responsibility for deporting some 77,000 Jews from 1942 to 1944. The document uncovered on Sunday takes on one of the last lingering dark spots in France's memory of its Nazi history: the question of whether World War I hero Pétain was a figurehead who had been manipulated into representing the collaborationist Vichy regime or a firm believer and active player in its anti-Semitic activities alongside the Nazis.

"This document demonstrates Pétain and Vichy were actually ahead of the Germans in terms of anti-Semitism at that point, and shows the desire of Vichy officials to prove they were at the vanguard of the emerging new order in Europe," Klarsfeld says. "These October 1940 French laws prepared the ground for the deportations of French Jews as part of the German Final Solution. When you see documents like this showing Pétain and his colleagues had already adopted a clear and harsh anti-Semitic outlook beforehand, it isn't surprising that Vichy provided the police that were needed to round up and deport French Jews when the Nazis requested them."

Pétain — who was in his mid-80s when he took the top Vichy post — was tried and sentenced to death for collaboration after the war. That sentence was commuted to life in prison — in part due to his WWI heroism, and arguments that the elderly Pétain had little real influence in actions that were depicted as the work of hardcore French fascists at the heart of the Vichy regime. Pétain died in 1951 — but only now can any doubts about his active role in persecuting France's Jews be put to rest for good.