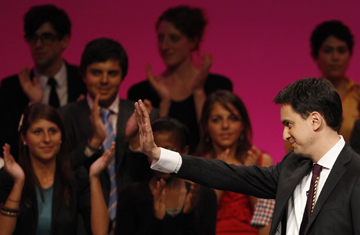

Ed Miliband waves after making his first speech as Labour Party leader at the party's annual conference in Manchester, England, on Sept. 28, 2010

Healthy sibling rivalry is all well and good, but Britain has just witnessed a contest of rare Shakespearean intensity: between two brothers, each with a burning ambition to lead the opposition Labour Party in the wake of its May election defeat, and each being championed by rival camps who spent much of the past few years at each other's throats. And now victory by the once outsider younger brother is threatening a final act of feuding to match that of the Montagues and Capulets.

David and Edward Miliband, the geeky offspring of the late Marxist academic Ralph Miliband, spent the past five months touring the county with three other candidates — addressing the party faithful and being largely ignored by the media and public — in a battle to pick up the crown laid down by former party leader Gordon Brown. Everyone said former Foreign Secretary David, 45, was the natural, centrist successor to the party's most electorally successful leader ever, Tony Blair. It was David who had the qualities and experience, they crowed, to take on the Liberal-Conservative coalition government on the vital center ground. If only he could develop his softer side. Younger brother Ed, 40, was routinely dismissed as too left-wing, too close to the Gordon Brown faction that had persistently attempted to undermine Blair's New Labour. But at least he had the human touch.

Yet many believe that, as one senior party member says, "there's not a cigarette paper's gap between them on policy." Perhaps that's not surprising from siblings whose paths to power have been so similar. Both were sent to the state-run Haverstock comprehensive school in north London, and both went on to study politics, philosophy and economics at Corpus Christi College Oxford. It was David who, true to his popular image, did best and emerged with the first-class degree.

Both dismayed their father by joining the Labour Party in their teens, and they later went to work for senior figures: David for Blair and Ed for Brown. And both were swiftly promoted to Cabinet positions once Labour was elected to Parliament, although it was once again David who got the higher-profile job, of Foreign Secretary — during which time he notably impressed Hillary Clinton — while Ed was given the less glamorous energy brief. The party and the British media came to view David as a shoo-in to be the next leader after Brown, despite his slightly odd image. Two years ago, for example, the media had great fun at his expense when he was pictured at a party rally waving a banana — presumably an energy-boosting snack.

So there was genuine surprise when Ed announced that after much consideration, he was running against his brother in the contest to replace Brown following Labour's loss in May. Despite protestations of brotherly love, many believed the older sibling was, as former Labour leader Neil Kinnock told a TV reporter recently, "deeply resentful." And while the five-month contest drew little media attention, there were persistent stories about a cooling of the relationship between them.

It came to a head when the results of the complex ballot of party legislators, members and unionists was declared at the party's annual conference in the northern city of Manchester on Saturday, Sept. 25. It was Ed who had seized the day, by the narrow margin of 1.3%, thanks largely to the support of union members. The pain on big brother David's face was for all to see, and later, in his own conference speech on Monday, he felt the need to tell anyone who was worrying about him, "I'll be fine."

The question now hanging over the Labour Party is what exactly he meant by that. Will the defeated brother stay and serve in a senior position, almost certainly shadow Chancellor, under his young brother? Or will he leave politics for a position in business or on the international stage?

As former Minister Caroline Flint told TIME after Ed's conference speech on Tuesday (which gave no hint of what his brother might be planning), "David should be given time to decide what he wants to do. But whatever his decision, the media will paint it as trouble for the party." Certainly, if he goes, it will be portrayed as a major blow to his brother's attempts to unite a fractious party. If he stays, there will be the constant fear of a rerun of the divisive and damaging soap opera that was the Blair-Brown relationship in their final years in power.

On Tuesday, Ed heaped praise on his sibling, describing him as an "extraordinary person" and speaking of the "graciousness" with which he had taken defeat. David sat alongside him on the stage, applauding Ed's declaration that he was not in the pockets of the trade unions or hard-line left-wingers by brushing off his "Red Ed" nickname.

And that's where this tale of fraternal rivalry stands for now — awaiting a final act that could have a profound effect on the new Labour leader and his bid to haul his bruised party back from defeat and into position to ensure, as he said on Tuesday, that the current coalition will be "a one-term government."