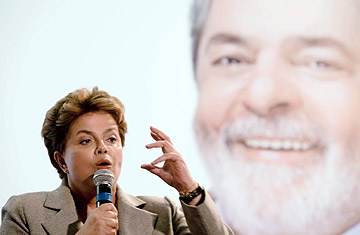

Presidential candidate Dilma Rousseff of the Workers' Party speaks during an election campaign rally in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Updated: Aug. 27, 2010

It's always tough getting people interested in party politics in Brazil, a nation where ideology is non-existent, political parties stand for little more than organized power grabs, and where, according to Transparency Brazil, 40% of the country's Congress has been found guilty of some kind of corruption-related crime. One of the best ways was to treat the subject with humor, because if you didn't laugh, you'd cry. Now, even that option is a non-starter, thanks to a new law that has prohibited the broadcast media from "in any way degrading or ridiculing candidates, parties or coalitions" running in the October elections for president, Congress and state governments.

The ban was designed to keep Brazil's satirical shows and comedians from lampooning politicians — supposedly to level the playing field for all candidates. It has been greeted as a cheap form of censorship. "Taking the humor out of the electoral process does not elevate the level of the campaigns, it doesn't enlighten people, and it doesn't make our politicians more respectable," said Helio de la Pena, a star of Casseta & Planeta, one of Brazil's most popular satire shows. "Quite the contrary, it weakens the debate [and] removes the presidential race from the conversations that take place on street corners and in company cafes."

The ban, which has reminded many Brazilians of the 21-year dictatorship that ended in 1985, applies to TV and radio and levies fines of between $12,000 and $61,000 on offenders. It was passed quietly last December as an amendment to the 1997 election law. What the ban has done is make an already torpid political struggle even duller. None of the three main presidential candidates can be described as charismatic. And rather than propose exciting new solutions for Brazil's myriad problems, all three have essentially endorsed the policies of President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and promised to continue where he left off.

(UPDATE: The Supreme Court partially lifted the ban on Thursday night, saying, "It does not fall to the state or any of its organs to define in advance what can or cannot be said by journalists or individuals." Supreme Court Vice President Ayres Britto maintained a ban on conduct that "clearly favored one of the parties" involved in a race, but said the ban on humor was artistic and political censorship.)

Dilma Rousseff, Lula's hand-picked successor, leads her centrist rival Jose Serra by between 8 and 18 percentage points in the polls, with the Green Party's Marina Silva a distant third. After polling neck and neck with Serra for several weeks, Rousseff has pulled ahead in the last few days, a beneficiary of TV ads that have highlighted her backing from the massively popular Lula. With Serra's campaign floundering, he has even played up his own admiration for Lula in an attempt to piggyback on the President's success.

Despite the ban, however, not all comedy has been stamped out — thanks to the fact that print isn't affected by the new law, perhaps because only a small portion of Brazilians read daily newspapers. Nor does it apply to the internet. And so viewers have turned to Twitter to propagate their own barbs amid recent political debates. The inadvertently hilarious behavior of the candidates themselves, moreover, does not require a laugh-track — as when Green Party presidential candidate Marina Silva chose to recite one of her own poems instead of summing up her positions at the end of one debate.

Rousseff is expected to maintain or extend her lead and could even win an outright majority on Oct. 3 and thus avoid a runoff four weeks later. That may be what Brazilians are hoping for. A quick end would deliver the coup de grace to a moribund campaign. And put Brazil's comedians out their misery.