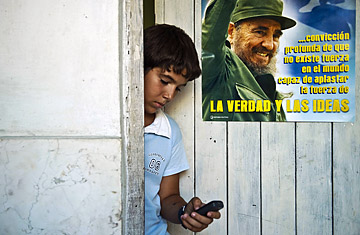

A boy uses a cell phone next to a poster of former Cuban President Fidel Castro in Havana

Fidel Castro, decidedly languid but reasonably lucid, showed up on Cuban television Monday evening, July 12, to warn the world that the U.S. is poised to attack North Korea and Iran. (We'll take that under advisement.) But the rare appearance by the 83-year-old former Cuban leader was more noticeable for what he didn't mention: last week's surprising decision by his younger brother, current President Raúl Castro, to release 52 political prisoners who had been arrested in 2003 during one of Fidel's harshest crackdowns on dissidents while he was President.

It's unclear whether Fidel's silence means he disapproved of the move. But the U.S. seems just as happy that the ailing autocrat, who ceded the presidency to Raúl four years ago for health reasons but still wields considerable influence, didn't make a big deal of freeing the prisoners (seven of whom arrived in Spain on Tuesday; the remaining 45 will be released in the coming months). That's because the Obama Administration isn't making a big deal of the dissidents' release either. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called the move "a positive sign" and "very welcome" but also downplayed it as "overdue." There was nothing in her statement to suggest that the Administration planned to respond in any way that might further engage communist Cuba with a view to promoting democratization.

The Administration is engaging Cuba on some bilateral issues such as immigration, mail service and containing the BP oil spill. But even if the political prisoners' release is overdue and their imprisonment an outrage to many international human-rights groups, the agreement to free them provides an opportunity that President Obama may fail to seize. When Obama last year abandoned his predecessor's draconian restrictions on Cuban Americans' travel to Cuba, he effectively tossed the ball into the Castros' court. Havana seemed to resist any temptation to reciprocate. But when imprisoned dissident Orlando Zapata Tamayo died in February as a result of a hunger strike to draw attention to the plight of Cuba's political prisoners — and others threatened to follow his example — international criticism nudged the more reform-minded Raúl to open negotiations with Cuba's Roman Catholic Church and the Spanish government, which resulted in last week's stunning announcement.

Many Cuba watchers saw the next move as being Obama's. One of the more obvious and less risky steps the Administration could take is to throw its support behind a bill currently moving through Congress that would lift the ban on U.S. travel to Cuba and loosen the 48-year-old U.S. trade embargo against Cuba to make agricultural sales to the island easier. Polls show that a majority of Cuban Americans back the measure, and last month, some 75 prominent Cuban dissidents, including internationally renowned blogger Yoani Sánchez, signed a letter insisting it would "facilitate the transition we Cubans so greatly desire."

Earlier this month, the House Agriculture Committee passed the bill, which must get through the Financial Services and Foreign Affairs committees before the full chamber can vote on it — a journey that could use some White House clout. But so far, even after the prisoner release, the Administration has confined itself to supporting a "robust debate" on Capitol Hill about Cuba policy. "It's absolutely mum on this," says Christopher Sabatini, senior director of policy at the Americas Society and Council of the Americas in New York. "But it reflects the surprising policy radio silence we're so often getting from this White House on Cuba and Latin America in general."

Sabatini's organization, in conjunction with the influential Cuba Study Group and the Brookings Institution's Latin America Initiative, will on Thursday, July 15, release a report titled "Empowering the Cuban People Through Technology." It will urge Obama to at least use his executive prerogative under the embargo to lift restrictions on U.S. telecommunications investment in Cuba. Obama last year did permit increased cell-phone and satellite links between the U.S. and Cuba to "promote the freer flow of information and humanitarian items to the Cuban people." But that opening has been too limited, says the report, which argues (as do tech-savvy dissidents like Sánchez) that Obama's democratization-via-information goal can realistically be achieved only by letting U.S. telecom companies operate inside Cuba.

The report argues that any economic benefits to the Castro regime from allowing U.S. telecoms into Cuba are outweighed by the social benefits to Cuban citizens. And it notes that while Havana exerts China-style control over Internet use, networking sites like Facebook are often uncensored so that tourists, a major source of Cuba's hard currency, can use them while on the island.

But pro-embargo groups insist just as emphatically that such moves would give the Castros a lifeline. And in Washington, the more hard-line Cuban-American cohort still trumps South Florida polls and dissident letters — especially since groups like the U.S.-Cuba Democracy Political Action Committee have doled out $11 million in congressional campaign contributions over the past five years, hoping to beat back Cuba measures like the new House travel bill.

Even though Washington's half century of isolating Cuba has failed to dislodge the Castros — and even though ramping up engagement with Cuba could very well help emerging democratization forces like the island's Catholic Church — the Obama Administration would rather avoid a fight with that flush and fierce lobby. Domestic political calculations, then, may mean passing up an opportunity to change the dynamic in one of the most intractable problems of U.S. foreign policy.