It seems even justice isn't recessionproof. On Tuesday, June 29, U.K. Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke outlined radical prison reforms that he said would both "shut the revolving door of crime and reoffending" and save money for the government, which is straining under a £135 billion ($230 billion) deficit. While Britain's coalition government must first conduct a review of sentencing policy and then reach agreement on how to proceed with the proposed policy changes, critics and supporters alike see the announcement as paving the way for alternative sanctions and a reduced prison population.

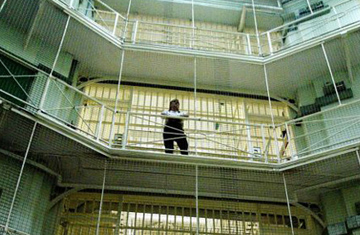

Speaking at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies at London's King's College on Wednesday, Clarke broke with Conservative orthodoxy by suggesting that taking the hard line on criminality — "banging up more and more people for longer" — doesn't deliver results. "Too often, prison has proved a costly and ineffectual approach that fails to turn criminals into law-abiding citizens," he said. "In our worst prisons, it produces tougher criminals."

Britain's prison population has nearly doubled since 1993, when Clarke last oversaw the prison service as Home Secretary. That year, England and Wales had a prison roster listing 44,628 inmates. Today it stands at 85,000 — "an astonishing number, which I would have dismissed as an impossible and ridiculous prediction if it had been put to me in a forecast in 1992," Clarke said. England and Wales together now have the largest prison population in Europe and one of its highest rates of incarceration, jailing 154 of every 100,000 residents, compared with 111 in Italy, 96 in France, 87 in Germany and 71 in Norway.

Clarke framed the need for reform in economic terms — a move that no doubt stems from the government's June 22 announcement of an emergency budget meant to eliminate the nation's deficit within four years. Keeping a prisoner in jail in Britain costs, on average, about £38,000 ($57,000) — more than it costs to send a child to Eton, an elite boarding school for boys. All told, the government spends about £2.2 billion ($3.3 billion) annually on the country's inmates. And the expenses are set to go up: under the previous Labour government, Britain embarked on a £4.2 billion ($6.3 billion) prison-building program — the largest in Western Europe — meant to boost the number of available prison slots from 87,000 to 96,000 by 2014. Current plans include the construction of five supersize jails that can hold 1,500 prisoners each.

If the current Tory-led government proceeds with its plans, the reforms will mark the first downsizing of the prison estate in decades. "The measure of success has been solely about whether a government has spent more public money and locked up more people for longer than its predecessor," Clarke said during his announcement. Despite all the money thrown at the system, though, reoffense rates rose 8% from 2006 to 2008.

To make a dent in public spending, Clarke will need to halt the expansion of Britain's prison infrastructure while finding more effective means of reducing crime. And though he didn't flesh out specific policies, he did say that to effect real change in an inmate's life, prisons must incorporate education, jobs and programs to combat drug addiction. To reduce the prison population, the state may provide "intelligent sentencing" like community sentences for offenders serving less than one year; at the moment, many of those who are sentenced to jail lose their jobs, their homes and their families, increasing the likelihood of their reoffending. Clarke also announced plans to reward voluntary and private-sector programs that successfully rehabilitate offenders inside and outside prison.

The call for a reduction in the prison population has already sparked outrage among the opposition. Writing in the Daily Mail, one of Britain's highest-circulation newspapers, Labour MP and former Justice Secretary Jack Straw claimed that society is safer because there were 75% more "serious and violent offenders" in prison in June 2009 than in 1997, when Labour came to power. "Does anyone seriously believe that crime would have come down and stayed down without these extra prison places?" he wrote.

International experience suggests that it could have. During the 1990s, Canada faced a budget crisis that required the government to slash public spending 20%. As part of those cuts, officials reduced the country's prison population 11%. The state released low-risk inmates and introduced more community-based sentences, and courts began to sentence criminals with greater restraint, turning to prison only as a last resort. Criminality didn't surge, nor did chaos reign: over the course of the decade, the number of assaults and robberies actually fell 23%, while murders dropped an astonishing 43%.

Finland also suggests that more lenient sentencing doesn't increase criminality. "Our experience shows that it's possible to reduce dramatically the use of imprisonment without having any visible or notable effect on crime rates," says Tapio Lappa-Seppala, director of Finland's National Research Institute of Legal Policy. In the late 1970s, he says, the country had one of the highest imprisonment rates in Europe, incarcerating three times as many people as its Nordic neighbors. But after academics suggested that Finland rethink its penal philosophy to align with values of the welfare state, officials reduced sentences, expanded alternative sanctions, reallocated money from prisons to social-welfare services — and watched imprisonment rates fall dramatically. Today the country incarcerates just 60 residents per 100,000, less than half the rate in Britain and a fraction of the rate in the U.S., which currently incarcerates 753 people per 100,000 — the highest rate in the world. "If you look at overall empirical criminological research, you'll see that what works to reduce crime isn't the prison system but instead social prevention," Lappa-Seppala says.

Back in Britain, Clarke hasn't drawn heavily on the empirical research, instead playing on the theme of belt tightening. "I take a very practical approach," he said on the radio Wednesday morning. "What I want to use the taxpayers' money for is results. The real challenge, if you are faced with a difficult, inadequate, not very nice person, is to try to make sure that he does not commit another criminal offense." Surely that's one approach that has currency in any economic climate.