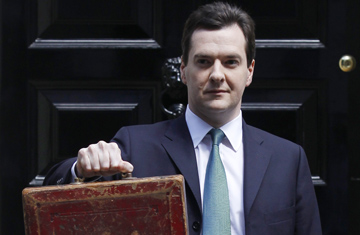

British Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne holds 19th century Finance Minister William Ewart Gladstone's old "budget box" outside 11 Downing Street in London on June 22, 2010

Now it's Britain's turn. On Tuesday, June 22, the nation joined a growing list of European nations taking drastic measures to pull themselves out of debt when Finance Minister George Osborne announced a sweeping program of cuts — and warned that it's going to hurt. For Britons, austerity 2010-style means an immediate, unprecedented squeeze on public spending and welfare that will hit virtually every family in the country. How well it works will decide the future of both the economy and the recently elected Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government.

Ministers have been warning for months that the only way to tackle the U.K.'s £156 billion (about $230 billion) deficit, which they lay firmly at the feet of the previous Labour government's alleged profligacy, is by inflicting unavoidable economic pain on every citizen for years to come. Now, with the government's first "emergency" budget, designed to pay off the deficit within five years, Britons have been told exactly how that pain will be administered and what anesthetic will be used to numb the worst of it.

In a package of measures described by Osborne as "tough but fair" and even "progressive" — and which will be watched by other countries agonizing over whether to follow a similar path — the Finance Minister announced an annual cut of £30 billion ($45 billion) in overall public spending, with only health and international aid exempt. About 6 million public employees, including teachers, nurses and police officers, will have their pay frozen for three years. Government spending will still stand at £711 billion ($1.05 trillion) come 2015-16, but the cuts represent an overall reduction of 25% in current commitments.

The annual welfare bill of £192 billion ($285 billion) will be cut by about £11 billion ($16 billion) a year, with families earning more than £40,000 ($60,000) a year losing major benefits. The much debated child benefit handed to every mother irrespective of her income will continue to be paid, despite demands for it to be tied to earnings, but it will be frozen for three years at about £20 ($30) a week. Britons will also see reductions in housing, disability and other benefits.

But the most controversial measure, and the one that may put the recently forged alliance between the Liberal Democrats and Conservatives under severe strain, is the long-predicted rise in the Value Added Tax (VAT) from 17.5% to 20% starting in 2011, which should put an extra £13 billion ($20 billion) a year into the government's coffers. The VAT is levied on the purchase of most goods except some essentials like food and children's clothes; it is widely accepted to be a regressive tax that hits the poorest the hardest and has traditionally been opposed by both Labour and the Liberal Democrats.

The announcement of that single tax increase immediately led to claims from the opposition Labour Party that Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron had broken his pre-election promise that he had "no plans" to raise the VAT. And it saw the Liberal Democrats accused of abandoning their long-term stand against the proposal in return for ministerial jobs.

To ease some of the pain on the poorest, Osborne cut the income tax for those paying the basic rate by about £170 ($250) a year and exempted 880,000 of the lowest earners from paying it altogether.

But opposition parties warn that the measures are so savage, they would not only disproportionately hit the poorest in the country but also risk putting the economy back into recession and even possible depression. Labour leader Harriet Harman pointed to figures from the independent Office of Budget Responsibility, which was recently created by the current government, showing that the measures would reduce likely economic growth next year from the 2.6% expected under the previous Labour government to 2.3%. That, she said, would undermine Britain's economic recovery and destroy 100,000 jobs.

Business leaders broadly welcome the package. Richard Lambert, head of the Confederation of British Industry, told the BBC the budget contains risks but said the risks of doing nothing this year were worse. He agreed that taxes have to rise alongside the spending squeeze as the only realistic way of tackling the deficit. Osborne had been careful to include a series of measures aimed at boosting business, including a 1% cut in the corporation tax — essentially a tax on profits — this year and for the next two years, ultimately reducing it to 24%. That's combined with other moves to reduce the tax burden on small businesses and cut the amount employers pay to the government in national insurance contributions, which help pay for workers' state benefits. The decision to levy a tax on banks' profits, estimated to collect about £2 billion ($3 billion) a year, had long been expected.

Trade-union leaders, however, were dismayed by the announcement. Dave Prentis, the leader of Unison, one of the largest unions, said he thought the budget was an ideologically driven move designed to cut the size of the state, then added, "A political decision has been taken — one that says 80% of the cost of this deficit has to be borne by public services and people in the public sector."

And this is the arena in which the political battle will rage. The Labour opposition, which had planned mainly unspecified spending cuts and tax increases in the event of re-election, will argue that the U.K.'s economic recovery is still too fragile for such strong medicine to be applied now. Labour will be looking for any signs that low growth may be undermining recovery. The government's critics will continue to claim that the cuts in spending go beyond what is absolutely necessary and that their ultimate aim is to move the country toward small government.

The coalition, on the other hand, is gambling that the measures will not only lead to long-term growth without risking a double-dip recession but also boost confidence in the British economy. But before that happens, other countries in Europe continue to mull over the idea of taking similarly drastic steps themselves — and the pain promises to spread.