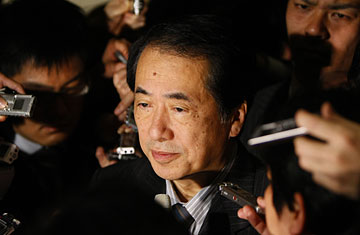

Japan's newly-appointed finance minister Naoto Kan is surrounded by reporters at Prime Minister's official residence in Tokyo on Jan. 6, 2010

There was a time when the appointment of Naoto Kan as the prime minister of Japan would have been seen, in the minds of many Japanese voters, as a moment of excitement, a sign that business as usual was going to change in Tokyo's hidebound political culture.

Unfortunately, that time was about 14 years ago. Back then, Kan was a crusading minister of health, and captivated Japan by confronting his own ministry: bureaucrats there had helped cover up a scandal involving tainted blood that led to thousands of patients getting HIV. Japan at that point was at sea; it had come off a decade — the 1980s — when it seemed to be taking over the world economically — but in the 1990s the bubble had burst. In 1996, at a time when the ministries in Tokyo seemed far more powerful than most politicians, Kan's outspokenness — and obvious anger — over the blood scandal struck a nerve. For a time he was the most popular politician in Japan.

Now he's not unpopular, exactly, but the years have taken a political toll on Kan, 63. Some of his fresh, reformist, man-of-the-people image was stripped away when he admitted in 2004 that he hadn't paid all the social security taxes he should have. He has also been close to political power broker Ichiro Ozawa, who himself has tried to be an agent of change in Japan, but done so using old-style, shakedown methods of fund raising. That too has tainted Kan's image.

But even if he were as popular as he used to be — and able to use the office of Prime Minister as a bully pulpit the way few have before him — it s hard to imagine him shaking Japan up significantly now; not when, as Yukio Hatoyama's successor as the head of the ruling DPJ (Democratic Party of Japan), he's going to have to spend all his time frantically bailing water out of a steadily sinking ship. Japan's public debt — inching close to 200% of GDP — makes Greece seem sober by comparison. Given that, Kan — who had served as finance minister under Hatoyama — said today that fiscal discipline would now be a central focus. "We can correct the current state in which [government] borrowing seems to keep growing indefinitely," he told a Tokyo news conference.

There are two potential problems with that goal. One is that Japan seems again in the grip of deflation. The country's core consumer prices fell in April for the 14th month in a row, declining by 1.5% in the year to the end of April. Kan, as finance minister, already indicated that he's for a weaker yen to help boost Japanese exports — something that would help offset the contractionary effects of higher taxes and less government spending. But he'll still need a lot of help from Tokyo's central bank if he truly wants to hit the fiscal brakes.

The other problem is that he can't do much of anything until an upper house election in Japan that is scheduled for July. Kan's DPJ is not a majority in the upper house of Japan's legislature, and given the party's current unpopularity, that's likely to remain the case after the elections, according to most political forecasters in Japan. As a result, says Robert Feldman, chief economist at Morgan Stanley, "policy stagnation is the most likely outcome." And at this point, in Japan as in many developed countries worldwide, "policy stagnation" is about the last thing it can afford. It seemed inevitable, when Naoto Kan burst onto the political scene in the mid-'90s, that he d be prime minister some day. Now he heads a party that the public, according to opinion polls, has soured on, at a moment that calls for the kind of decisiveness that once seemed a Kan trademark. In politics as in life, timing is everything. You could forgive Japan's new prime minister if he wished his might have been better.