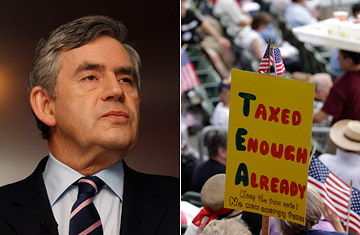

British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, left, and an American government protest

Dan Hannan was sick of turning over so much of his paycheck to taxes, he was disgusted as he watched the government's attempts to fix the economy by hiring thousands of workers instead of investing more in the private sector and he worried about his country's leader ceding sovereignty to supranational bodies. So Hannan decided to found a tea party. That may sound familiar in a country where some polls show 1 in 10 Americans define themselves as Tea Partyers. But Hannan isn't American; he lives in the English seaside town of Brighton.

Hannan and a small-government group called the Freedom Association threw an ad hoc event at the Brighton Hilton in February, advertised it on Facebook and were surprised when 300 people turned up — more than 50 had to be turned away because the room was too small. "We're starting from a different place than the Tea Partyers in the U.S.; British people don't march very easily," Hannan says in a phone interview. "So I was really encouraged by the enthusiasm and the turnout."

Any sense of irony that some Britons are now trying to emulate the event that once sparked a rebellion against them is lost on Hannan. He believes that Britain's greatest gifts to the world were the beliefs — no taxation without representation paramount among them — it exported to America and has since lost. "In a way, I'm trying to repatriate our revolution, trying to bring the same British sensibilities and principles back here," he says. His key target appears to be the European Union, a body that he alleges taxes Britons without adequately representing them. "What's changed everything is the crisis in Greece. Next time, they won't be able to go to the German taxpayers and say, 'Please bail us out,' " Hannan says. "So they want to create a kind of European federal reserve based off a new tax — a pool of bailout money for if and when this happens again so the [E.U.] won't have to go begging the individual governments for money."

Hannan, a lifelong conservative from his Oxford days, is a member of the European Parliament, a body he'd prefer to see dissolved. And herein lies a big difference between the American and British tea party movements: the U.S. one started as a grass-roots rebellion against Big Government. Hannan's event was more a top-heavy affair. He gave a long speech, introduced by the chairman of the Freedom Association, Roger Helmer, another British member of the European Parliament. The villain in this story wasn't President Barack Obama; it was Prime Minister Gordon Brown, head of the Labour Party. The Labour government "has raised more than a trillion pounds in additional taxation since 1997," read the Facebook notice for the event. "Yet, unbelievably, Gordon Brown has still managed to run up a deficit of 12.6% of GDP (Greece's is 12.7%). A far lower level of taxation brought Americans out in spontaneous protest last year."

The biggest difference, says Hannan, may be that his group was not "presented on TV as rednecks." Indeed, the first meeting was the picture of civility and decorum. There were no signs or demonstrators dressed up as Revolutionary War patriots, no fist pumps or angry shouting. In fact, tea was served. "I'm afraid it was all frightfully low-key, British being British," says Simon Richards, director of the Freedom Association, a group of about 4,000 founded in the wake of Margaret Thatcher's reign to continue her conservative principles. Association members are hoping that their next event, scheduled for July 11 in the original town of Boston in Lincolnshire, will be more colorful. They've bought giant teacups and saucers, and they may even symbolically dump some tea (at least, what they don't consume) into the harbor.

Despite the differences, the group's core tenets are in line with those of the American movement: small government, low taxes and a belief that it's the market system rather than government that will keep the economy humming. Hayden Allan, deputy head of press for the Conservative Party, is quick to note that the tea parties have had no impact on the election and don't look likely to. But some of their ideas resonate with elements of a society living under a much higher tax burden than their American equivalents do — the top British earners are taxed more than 50% of their income.

Taxation has become a hot button in next month's British parliamentary election: Labour had proposed increasing the National Insurance, which opponents call a jobs tax. Conservative Party front runner David Cameron came out against it, boosting his campaign. "The [American] Tea Party movement has caught a lot of people's imagination in the U.K., and the frustrations are very, very similar," says Mark Wallace, campaign director for the TaxPayers' Alliance, which started six years ago with just a dozen supporters and now boasts 40,000 members. "A lot of people are angry about government waste, what with the scandal over members of Parliament's flagrant expenses at the cost to the British taxpayers last year. They're angry that no political party currently represents their frustrations." The Conservative Party should heed that warning — the American Tea Party movement is often at odds with GOP leadership, and in many states it has fielded candidates to challenge Republican incumbents, often leeching millions of fundraising dollars that might otherwise have filled Republican coffers. America's Republicans would be the first to warn Britain's Tories that a tea party movement, while generating support for Republican issues, can also be hard to control.