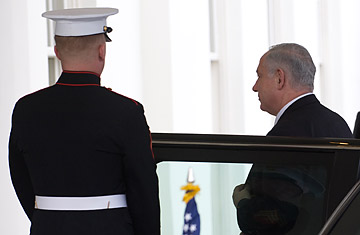

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu walks into the West Wing of the White House in Washington on March 23, 2010 to meet with U.S. President Barack Obama

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's Washington visit this week has failed to resolve his differences with the Obama Administration over the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Having twice delayed his departure as his team negotiated with U.S. officials over a set of confidence-building measures that Israel would offer the Palestinian leadership in order to coax them into talks being orchestrated by Washington, Netanyahu finally left town Wednesday night with no accord. Officials from the two sides are to continue negotiating on the issue in the coming days. Netanyahu's visit, if anything, reinforced the idea that the current Israeli government is at odds with the U.S. over the question of settlements, East Jerusalem and how to achieve peace with the Palestinians.

Netanyahu reportedly balked at White House demands earlier this month that Israel refrain from further construction in East Jerusalem. Indeed, he used his time in Washington to repeatedly restate his government's policy on Israeli settlement in East Jerusalem that had triggered a crisis during U.S. Vice President Joe Biden's recent visit to Israel. And the White House made no effort to conceal the discord, condemning new Israeli construction plans revealed during Netanyahu's visit and dispensing with the traditional photo opportunity and joint statement during Netanyahu's White House visit Tuesday evening. While U.S. officials sought to press Netanyahu to make a series of gestures to build Palestinian confidence in a new round of talks, the episode has instead reinforced the widespread skepticism of the prospects for the Netanyahu government and the Palestinian leadership being able to reach a peace agreement.

In the furor that followed the announcement, during Biden's visit two weeks ago, that Israel was planning to build 1,600 new homes in East Jerusalem, the Administration demanded Israel halt new construction in those parts of the city it occupied in the war of 1967, but which are claimed by the Palestinians as their future capital. Not only did the Israelis demur, but hours before Netanyahu arrived at the White House on Tuesday it emerged that Israeli authorities had approved further construction at yet another site in East Jerusalem. No surprise there, since Netanyahu had on Monday told the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), "Jerusalem is not a settlement. It is our capital ... Everyone knows that these neighborhoods will be part of Israel in any peace settlement."

Netanyahu's claims may have been a crowd-pleaser at AIPAC, and they went unchallenged on Capitol Hill. Still, as far as the U.S. government and the rest of the international community is concerned, Israeli construction in East Jerusalem is settlement activity. Whereas U.S. Presidents typically use words like unhelpful to describe it, on Wednesday the mild-mannered U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon was more forthright, denouncing the new housing units planned by Israel in East Jerusalem as "illegal." Israel's claims on the parts of the city it captured in 1967 are not internationally recognized, and Netanyahu's claim that Jerusalem is Israel's capital is called into question by the fact that no country has its embassy in the city. Even Netanyahu's immediate predecessor, former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, said on the eve of his departure from office in late 2008 that in order to achieve peace, Israel would have to "withdraw from almost all of the territories [occupied in 1967], including in East Jerusalem."

In Washington, Netanyahu reportedly talked with Obama for some 90 minutes on Tuesday evening, then sequestered himself in a different room in the White House with his advisers for another hour and a half before holding a second half-hour meeting with the President at the Israelis' request. But even that failed to bridge the gap between the two sides over what would constitute an acceptable approach to restarting the peace process, and the Israeli leader remained in Washington Wednesday as aides from both sides worked on the issue. The Administration clearly fears that the hard-line position staked out by Netanyahu on Jerusalem jeopardizes any prospect of getting the Palestinians or the wider Arab world to engage with him, rendering any renewed peace effort stillborn. As Olmert pointed out, no peace agreement would be accepted by any Palestinian or Arab leaders that didn't give the Palestinians control of part of Jerusalem.

Netanyahu insists that Israel is ready to resume direct negotiations, and blames Palestinian demands for a complete settlement freeze for creating an impasse. But his stance on Jerusalem may have simply reinforced the Palestinian leadership's argument that no deal can be done with the current Israeli government. (Of course, the Israelis might counter that the current Palestinian leadership with which it is being asked to negotiate has questionable political authority over its own people.) Still, the Obama Administration appears inclined to force Netanyahu to make a choice between pursuing a peace process whose contours "everybody knows" — to borrow his phrase — and being put in a diplomatic time-out.

Observers sympathetic to Netanyahu paint him as the prisoner of a right-wing coalition in which settlers and other extremist elements are well represented. Making concessions on Jerusalem, the argument goes, would force the collapse of Netanyahu's government. Perhaps, but what that argument ignores is that, if he wants to make concessions for peace, Netanyahu has a willing coalition partner available in the form of the centrist Kadima Party, whose 28 seats make it the largest party in the 120-seat parliament. Together with the 27 held by his own Likud Party and the 13 held by Labor (which is already in his coalition), Netanyahu could easily muster a governing coalition committed to implementing a two-state peace — if he could persuade his own party to do so and, more importantly, if he intends to go there himself. That, fundamentally, is the question currently being tested by the Obama Administration.