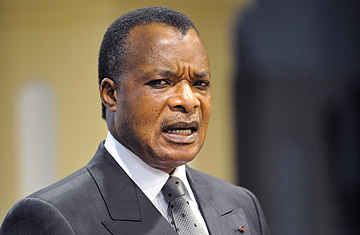

President of Congo, Denis Sassou Nguesso

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the West moved quickly to crack down on the money laundering and secret banking systems that fund much of the terrorism in the world. But as evidence in both the U.S. and Europe suggests, illicit finances continue to circulate around the globe — and quite often the money has nothing to do with violence, but plain greed. Indeed, a new report released by the U.S. Senate this month cites cases of huge volumes of suspect cash being moved from Africa to the U.S. for no other reason than to fatten the bank accounts of crooked leaders, shady arms dealers and conniving middlemen. And experts warn that if these people can still shuttle suspected corruption money across borders for personal gain, similar methods remain open to terrorists, too.

"As long as mass corruption, dirty money and banking secrecy are not eradicated together as a single priority, you'll never defeat the sub-activity within that funding terrorism," says François Valerian, head of private sector programs at the Berlin-based anti-corruption organization Transparency International. "Western nations recognize the urgency to treat this problem when it involves terrorism, but they become more pragmatic when it's in the form of ordinary corruption bleeding entire countries dry."

Proof that much work remains to combat both was provided on Feb. 4 when the U.S. Senate's subcommittee on investigations released its inquiry into money transfers from top African officials to the U.S. via loopholes in a section of the Patriot Act designed to crack down on illegal terrorism financing. The 330-page report scrutinized moves by top political, economic and business leaders from the notoriously corrupt nations of Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Nigeria to determine if they either violated or sought to side-step laws prohibiting money laundering. The report not only found evidence that several powerful officials (known as "politically exposed persons," or PEPs) exploited legal loopholes in moving suspicious funds to the U.S.; it also discovered that American bankers, lawyers and realtors were eager to facilitate those transfers.

"We've got significant holes in our protection," Democratic Senator Carl Levin, the chairman of the Senate Homeland Security panel, said in discussing the findings. "A key point here is that even though our banks have become more vigilant and they've created barriers against dirty money, foreign officials still get access to our financial system."

That's because the law itself created the means for the PEPs in the Senate investigation to gain that access. The Patriot Act made it illegal for individuals or businesses in the U.S. to accept money generated by corruption abroad, deeming it as being complicit to money laundering. But in doing so, the law exempted hedge funds, realtors and escrow agents, and made it possible for foreign officials to use American lobbyists, lawyers and university officials to get around the money laundering ban.

How? The report says that Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the son of Equatorial Guinea's president, relied on American lawyers, bankers and real estate agents to bring a total of $110 million in suspected dirty money into the U.S. via a complex system of shell accounts. The report also described how Omar Bongo, who ruled Gabon for nearly 42 years until his death last June, transferred $18 million into a U.S. account with the help of an American lobbyist. Similarly, the ex-wife of former Nigerian Vice President Atiku Abubakar is alleged to have helped shift $40 million into U.S. banks via offshore corporate accounts. These and other cases in the report suggest that U.S. efforts to cut off the flow of tainted funds still have a long way to go. "It's a long-standing goal of ours to try to see if we can keep corrupt money out of this country so we don't aid and abet people who pay this money," Levin said during a briefing earlier this month. "Particularly now, when we're focusing so much on the threat of terrorism."

But as the cases in the report reflect, the objective of the vast majority of tainted money transfers is the self-enrichment of corrupt officials who've pilfered public funds, not terrorism. And that's clear outside the U.S., as well. In France, Transparency International has brought a case against three African leaders — Congo's Denis Sassou Nguesso, Equatorial Guinea's Obiang and Bongo's estate in Gabon — claiming they allegedly used public funds to purchase around $200 million in French properties for themselves. A group of Cameroonian nationals based in France has also lodged a lawsuit in Paris accusing Cameroon President Paul Biya of buying French homes worth hundreds of millions of dollars with taxpayer funds. The three surviving leaders have rejected all accusations of corruption levied against them.

However, prosecutors in cases like these still face significant legal hurdles in trying to reclaim public assets suspected of being stolen by political leaders. Last month, a Swiss court ordered $4.6 million in frozen accounts to be returned to former Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier after his family appealed a lower court's decision to turn the money over to charities, arguing the statute of limitations on any purported wrong-doing had expired. Moreover, despite a 2005 U.N. convention setting legal requirements for fighting corruption, Valerian says many Western countries have been slow to apply the measures and tend to view corruption in the developing nations they deal with as being too rife and politically touchy to battle.

"Lots of business is secured and done in the developing world by nations and companies that adopt a so-called pragmatic tolerance of corruption," Valerian says. "When contracts are signed and money is made it benefits everyone — except local publics."