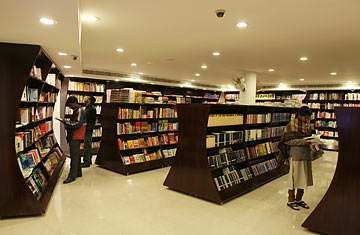

An Indian bookstore

Satyajit Sarna didn't like being a corporate lawyer. So the 24-year-old from New Delhi quit his job and instead spent months writing a novel about what he knew best: being a corporate lawyer. A decade ago, a literary leap of faith like Sarna's may not have had much chance for a soft landing. But the Indian economy is growing, and so is its appetite for books. So instead of heading to a courtroom this week, Sarna packed his manuscript and headed south to the Jaipur Literature Festival to look for a new job — as an author.

The festival, located in the desert of the Indian state of Rajasthan, is a star-studded literary event, but with a breezy, shoes-off feel. Held almost entirely outdoors, during the daylight hours overflow crowds sit cross-legged at the entrance of the Mughal tent. Turbaned waiters serve tea in clay cups. When the day cools in the evening, women in saris sip on Indian wine and tables with mixed accents relax as the vibe morphs from seminar to rock concert.

India has a distinguished history of producing great writers, but until recently, not much of a track record of actually buying their books. That lack of enthusiasm was due, in part, to sheer economics; books were largely considered a luxury item that could only be used once. For years, Penguin was the lone foreign publishing presence in India. But as the economic outlook in the country brightened, so has the outlook for aspiring authors and publishers. Sensing a new and growing market, foreign publishers like Harper Collins and Random House have set up shop in the outskirts of New Delhi. Retail space for books exploded, with big chain bookstores opening in cities, airports and hotels across the country. "It all happened pretty quickly: shopping malls came up, big bookshops came up, and people had the spending power," says Anantha Padmanabhan, the head of sales at Penguin India. "In 2003 everything curved upwards. A mass injection took place."

That injection is evident at this year's Jaipur Literature Festival. Now in its fifth year, the gathering has mushroomed in size and reach to become one of the continent's most influential, with more than two hundred authors from around the world set to attend. "The idea of the literature festival is really to bring together the interest in Indian writing, which has been growing phenomenally, but is now really propelled by the fact that people are looking to India both as an economic power, and as a place of contemporary writing," says Sanjoy Roy, the producer of the event.

Despite the enthusiasm, the exact economic trajectory for the books is still open to interpretation. The Indian market, despite being considered one of the fastest growing in the world for English language titles, is unique in the world. Unlike in the U.S., where purists lament the disappearance of the independent bookshop from Main Street, three quarters of India's estimated 2000 bookstores are small, independent dealers, the majority of which still don't use computers to track sales. "So there's no way of finding out exactly what's happening," says Padmanabhan.

The lack of computerized coordination of sales data among remote bookstores means that publishers rely heavily on newspaper best-seller lists and, perhaps more importantly, on feedback from bookstore owners to divine what kind of book the Indian reader want. There is no equivalent to Oprah Winfrey — whose television show has been launching best-sellers in the U.S. for years — so boosting sales still requires a personal touch. Authors looking to increase their numbers are compelled to visit bookstores large and small to talk up their book. This word-of-mouth method among booksellers still reigns supreme in India. "They are the guys who are going to be hand-selling a good book to customers," says Padmanabhan.

It seems to be working. When well known Indian business scion Nandan Nilekani's first book hit the shelves this year, Penguin sold over 60,000 hardbacks — a total that raised expectations for best-sellers in the country. A decade ago, the company wouldn't have dreamed of printing more than 7,000 copies, says Padmanabhan. When the fourth book in the "Harry Potter" series was released in 2001, Penguin sold 30,000 copies. That was a good haul, but still small in comparison to the U.S., which sold 3.8 million copies, and the U.K., which sold another million. By its last two installments, 270,000 hardback copies of each flew off the shelves. "We know that more books are being published and more books are being sold — there's just no doubt about it," says Namita Gokhale a co-founder of the Jaipur Literature Festival.

In the corner of the lawns, a tent houses a makeshift book store. Brimming with people, inside large metal racks are wobbly with books by authors near and far. A paperback copy of Malcolm Gladwell's latest is propped next to Nandan Nilelkani's home-grown bestseller. Privanka Malhotra runs Full Circle book stores, an independent chain of four stores, and has seen the difference that the influx of publishers has had on the the market. "The fact that now we have a lot of publishers that have come in from America and Europe, we have access to a lot more [books]," she says. "It's growing, but we still have a long way to go."

One giant hurdle that looms large for everyone at the festival — and the industry across the country — is piracy. Like the latest chart topping CDs or DVDS, at stoplights around the country hawkers peddle cheap, illegal copies of the latest book titles at car windows for a fraction of the price. That's hard for small book stores like Full Circle to overcome. "The minute you have a best seller, it doesn't even take five days for book pirates to sell it on the street," laments Malhotra. "You drive down any of the main roads in Delhi, and you'll see all the latest titles for less than half the price." And the cost to the industry is significant a significant one: For the most popular titles, illicit sales of pirated copies can rival store-bought sales figures.

Despite the challenges of the business, it's a good time to be an author in India, says Malhotra. "They now have so many options to be published." That's exactly what aspiring author Satyajit Sarna is banking on as he sizes up the festival crowd, looking for his big break. But figuring out how to become the next Indian literary star isn't easy. "My book is a dark coming of age story where nothing really works out for anyone," he says. "I don't even know if there's a market for that."