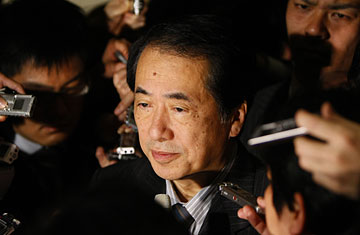

Japan's newly-appointed finance minister Naoto Kan is surrounded by reporters at Prime Minister's official residence in Tokyo on Jan. 6, 2010

Mired in deflation and lagging productivity, Japan's economy has a new casualty: long-time politician Hirohisa Fujii. On Wednesday, just four months into his new administration, Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama reluctantly accepted the resignation of his 77-year-old finance minister. Citing poor health and not enough stamina to make it through the next Diet session slated to begin Jan. 18, Fujii stepped down from his post after working tirelessly on the government's record stimulus package of $78 billion (7.2 trillion yen) and unprecedented $997 trillion (92.3 trillion yen) budget for the fiscal year beginning in March. Hatoyama wasted no time, however, picking Fujii's successor in Deputy Prime Minister Naoto Kan, 63, a the Democratic Party of Japan's founder and first party leader, perhaps best known for battling bureaucrats.

The question now is whether Kan, who was sworn in Thursday afternoon, will be able to steer the Japanese economy through the quagmire of a soaring deficit and deflation — and ensure passage of the 2010 budget, a priority for Hatoyama. Japan's public debt is mounting to nearly 200% of GDP, and many economists point out the need for reigning in spending and fiscal consolidation. At the same time, Japan is the only major global economy suffering deflation, which many in government worry could deteriorate into a deflationary spiral. "If we put a priority on fiscal consolidation, then public spending needs to be cut. But if we put the emphasis on getting out of deflation, then the usual prescription is to increase public spending," says Masaaki Kanno, chief economist for JPMorgan Securities in Tokyo. "Fujii was the right person to balance those two conflicting objectives." Kanno says that Kan will now face the same challenges.

Kan reportedly told Hatoyama this week that there must be someone better suited to the position than himself, but some observers say he's the obvious choice. A strong ally of Hatoyama, Kan has been involved in the budgetary process and economic policy as Chief of the bureau of national strategy. Kan will remain deputy P.M. in his new role, but give up his seat in the national strategy bureau to Yoshito Sengoku, the minister of Administrative Reform who was also floated as one of the candidates this week for finance minister. Kan has cultivated a strong image as an activist-turned-lawmaker, exposing a scandal involving HIV-tainted blood products during his earlier tenure as health and welfare minister. He has remained a vocal member of the Diet — a trait that should serve him well as the head of what is generally considered the most important ministry in Japan's government.

Given Kan's history of fighting bureaucratic power, however, some speculate that his relationship with the Ministry of Finance could be more antagonistic than that of Fujii, who Kanno describes as "an old-type, conventional ministry of finance guy." Kan has already said he intends to make the ministry more transparent in its day-to-day operations and budget formulation, a primary objective of the bureau of national strategy. But Kan's true test will be to go before the Diet to defend the budget, which includes expenditures on social programs and free high school tuitions that are in line with the party platform and are largely favored by the public.

Another critical issue facing Japan's economy is the strength of the yen. Kan has spoken out against a strong yen; Fujii favored it. The yen rose to a 14-year high against the dollar in late November, and has been a major cause of anxiety for the nation's exporters. When the yen strengthens, the Nikkei falls. "We hope that the currency issue should not be a source of high volatility in the coming months," says Kanno. "No one is happy with that." Kanno speculates that a strong yen, leading to a drop in the Nikkei and public sentiment, could trigger a deflationary spiral.

Such a turn in the economy would aggravate Hatoyama's growing list of woes, which already include a political donations scandal and a falling approval rate, now below 50% and down from 70% when he took office in September. With upper house elections looming in July, Hatoyama's appointment of Kan might have greater political implications than economic ones. Already a Cabinet member, Kan is Hatoyama's quick fix to avoid what could have been a long — and unpopular — delay in finding a replacement. Kan's new position allows him a more hands-on role with economic policy, for which he can start to prepare immediately. As the prime minister said yesterday, "I appointed the person who watched [the budget process] most closely in order to keep the damage to a minimum."