Copenhagen delegates who find their motivation flagging during a long evening session on the finer points of cap and trade could do far worse than to stop in for a meal at Noma. At chef Rene Redzepi's astonishing restaurant, dinner begins with a tiny quail egg served on a bed of smoldering hay (all the better to infuse the lush yolk with the haunting flavors of barnyard and smoke). In both its sustainably raised, locally foraged credentials, and its all-around deliciousness, the egg is Noma's small but potent culinary reminder of why saving the planet matters.

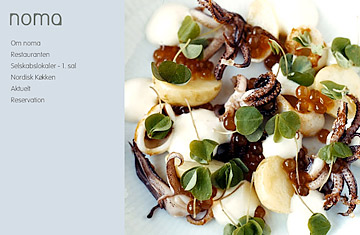

The restaurant is housed below the wooden beams of a renovated dockside warehouse and its mildly ramshackle appearance belies two Michelin stars, as well as the fact that it was named third best restaurant in the world on the prestigious annual list put out by Restaurant magazine. (No. 1 is Ferran Adria's El Bulli in Spain and No. 2 is Heston Blumenthal's Fat Duck in Britain.) The animal skin rugs thrown over the back of the chairs and the bleached wood remind you that this is ground zero for the new Nordic cuisine, in which a traditional focus on pickling, shellfish, a lot of rye and root vegetables is combined with the full panoply of a modern professional kitchen's tricks. Here, a single raw razor clam comes encased in a magical tube of parsley gelee, and a gorgeous piece of pork belly gets the sous-vide treatment (vacuum sealed and cooked at extremely low temperatures), before being crunched up beneath a crust of locally harvested potatoes.

The key word in that sentence is local. Any number of restaurants around the world have embraced the seasonal/regional/sustainable aesthetic, but at Noma, Redzepi shows you — with every bite — why it is important. The flavors he serves, whether a puckery ribbon of pickled kohlrabi, or a fatty, smoky bite of musk ox bone marrow, could not possibly come from any other place on earth but Scandinavia. "Like no other restaurant, Noma has been able to define Scandinavian cuisine by focusing entirely on the unique character of regional produce and presenting them in a clearsighted, innovative way," says Per Styregard, editor of Sweden's Gourmet magazine.

The young chef himself is given to plucking tart sea buckthorns from the beach, and pulling up ramps from the forest floor outside of Copenhagen. But his role as forager-in-chief is not affectation; Redzepi has, along with a handful of other chefs, put Scandinavian cuisine on the culinary map by highlighting the distinct products and flavors attached to that part of the world. Which is not to say that he's a traditionalist: this is a guy willing to serve live shrimp unadorned to his diners and to PacoJet his walnuts until they turn into frozen powder for dessert. The combination is something altogether new: by showcasing his local ingredients in a way that is part molecular gastronomy, part lightness of touch, he makes it clear why they're worth preserving and cultivating.

And he's persuaded others as well. Not only has Redzepi trained a number of chefs who have gone on to open their own well-regarded Nordic restaurants, but he's put the cuisine on the international foodie map. Better than anyone else, says Styregard, "Noma has successfully managed to communicate this new approach to Scandinavian cuisine to a broad international audience." A quick flip through the food magazines or the line-up at chefs conferences in the past couple of years proves he is right: Nordic is hot.

But you don't need to know that to enjoy his food. Any climate negotiator sitting down to Redzepi's beef tartare, for example, will get a pristine rectangle of magenta-colored meat, swathed with horseradish and neatly topped with rows of sorrel leaves. The beef is pastured and locally raised, and the taste induces superlatives — cold, rich meat, spicy horseradish, lemony greens. But more than anything, it's the visuals that stun. So simple and so delicious, Noma's tartare looks for all the world like a square of clover. It looks, in other words, like the perfect Scandinavian field for feeding healthy, happy cows, or, not incidentally, for sequestering carbon.