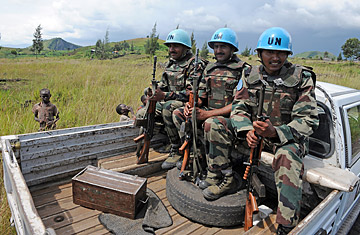

United Nations Mission in Democratic Republic of Congo.

It is startling because it is so mundane: rebels in eastern Congo apparently have no trouble circumventing the punishing U.N. sanctions aimed at bringing an end to the years of fighting in the lawless region, according to a new U.N. report released this week. One way they do it is by moving money through Western Union.

Less mundane and even more startling is the fact that, according to the U.N. report, a host of religious groups and charities have knowingly given money to Congolese operatives and their associates several times in recent years. Those funneling money to the rebels include charitable groups in Spain, a Catholic priest in Italy and another Catholic priest in Tanzania, Brother Constant Goetschalckx, whose refugee education organization won the $1 million Opus Prize in 2007. The prize, the world's largest for faith-based entrepreneurship, is meant to "recognize unsung heroes" working to fight poverty.

These and other revelations in the exhaustive report, issued by a U.N.-mandated group of Congo experts, erases any doubt that the multiple rebel groups operating in eastern Congo, led by the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), have a vast, sophisticated network of political and financial supporters around the world. The confidential report, which was obtained by TIME, also makes clear that the international community and the 20,000-strong U.N. peacekeeping operation in eastern Congo have been powerless to cut off the rebels' prodigious sources of funding.

"The army and the peacekeepers have basically dealt with the FDLR militarily without cracking down on their financial and political support networks," said Jason Stearns, a Congo expert who had helped to draft previous versions of the U.N. findings. "The report says this is a deeper problem than going after them with an army. These guys are colluding with military officials throughout the region — the head of intelligence in Burundi, senior army commanders, important gold traders."

This is not the kind of news the United Nations wants to hear. In fact, the report is an implicit condemnation of the recent strategy adopted by the U.N. peacekeeping mission in Congo, known by its French acronym MONUC. The operation began in 2000 as a way of monitoring the end of a five-year civil war in Congo, but the violence has dragged on for years and the U.N. has been unable to rid the region of insurgents, some of whom crossed the border from Rwanda after the genocide of the 1990s. After taking the lead role in fighting the rebels in 2004 and 2005, the peacekeepers have shifted their mission to supporting the Congolese army, providing fuel, transport, logistics and other help.

One of the most striking things about the U.N. report is what's missing. There is no discussion of the rebels' ideology, their goals, their prescription for a better future in Congo. What seems to be most clear is the extent to which the Congo insurgency has become a battle for resources, such as gold, timber and cassiterite, the chief component of tin. Congo estimates that about 40 tons of gold — $1.2 billion worth — is smuggled out of the country each year. Much of it goes through Uganda or Burundi and ends up being sold in the United Arab Emirates, according to the report. The rebels — as well as some members of the Congolese army — have had little trouble circumventing U.N. and government due-diligence requirements.

Part of the Congolese government's strategy for ending the insurgency has been to incorporate one former rebel group, the National Congress for the Defense of the People, into the army. But that hasn't stopped the one-time rebel commanders from stealing arms and minerals or colluding with the very rebels they're supposed to be fighting against. It hasn't stopped other army units from doing the same thing, either. The report details how the U.N.-backed government troops allegedly raped and tortured civilians and forced children into military service. It reveals several cases in which army officers diverted or tried to divert assault rifles, grenades and ammunition to rebel groups. Sometimes, army troops warned rebels of their presence by firing into the air, and released rebels who were captured in the fighting. "Scores of villages have been raided and pillaged, thousands of houses have been burnt and several hundred thousand people have been displaced in order to escape from violence generated by military operations," the report said.

The U.N. doesn't escape blame, either. The report says that MONUC worked closely with a Congolese general named Bosco Ntaganda, nicknamed "The Terminator," who is wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes for enlisting child soldiers. Ntaganda's troops have taken control of several areas and are believed to reap about $250,000 a month in taxes on charcoal, timber and minerals, the report said. "It really does punch a hole in the argument that has been put forward by MONUC, which claimed that these military operations, while difficult and problematic, are bringing results," Anneke Van Woudenberg, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch in London, tells TIME. " This report in excruciating detail shows that this is not the case."