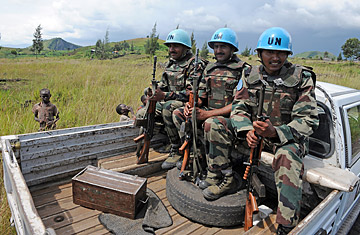

United Nations Mission in Democratic Republic of Congo.

At the national stadium in the Guinean capital, Conakry, it's oddly quiet — the only sounds that can be heard are the muffled beats of a drum band practicing nearby. The other strange thing in a dusty and garbage-strewn city is how clean the stadium looks. Many of the walls and exit tunnels have been freshly painted. That's the only sign of what happened here on Sept. 28 when human rights groups say Guinea's year-old military junta opened fire on an opposition rally, killing 157 people. Locals say there was so much blood, the stains soaked into the concrete. Hence the regime's sudden need to redecorate.

But memories cannot be painted over so easily. The day of the massacre, Guinea's broad-based opposition movement — called Forces Vives, literally meaning Forces Alive, and made up of political parties, labor unions and civil society groups — drew tens of thousands of supporters to a rally in the stadium to protest what it called an increasing authoritarianism in the country. The junta struck back with brutal force. According to witnesses and human rights groups, the army first locked the protesters in behind metal doors hastily electrified with lethal current, then opened fire. The wounded were finished off with bayonets. Scores of women were raped in broad daylight.

The massacre stopped Forces Vives in its tracks. The government has since banned political rallies, and the opposition movement doesn't look set to defy that. "Everybody is scared," says Souleymane Bah, the president of an umbrella movement of human rights organizations known by the acronym CODDH. "Me too." Bah was beaten unconscious in the stadium and lay there for two hours before eventually finding his way out.

What worries the opposition most now is that the junta, which took power in December 2008 and is led by a former army captain, Moussa Dadis Camara, seems to be preparing for more repression. Intermittent beatings and killings of opposition supporters continue, says a Guinean human rights worker who requested anonymity. And there are widespread reports of new militia training camps that have been set up in the hinterlands to train new paramilitary forces. Thierno Sow, president of the Guinean Organization for Human Rights (OGDH), claims the camps are outside a town called Forecariah near the border with Sierra Leone and that they are being run by mercenary instructors from South Africa and Israel. Corinne Dufka, the West Africa regional director for the New York-based Human Rights Watch, could not confirm the existence of foreign instructors, but said the training "is definitely going on." The junta is "digging in," she says.

When Camara first took power, Guineans seemed willing to give him a chance to lead. He filled a vacuum following the death of the unpopular and corrupt President Lansana Conte, who had ruled with an iron fist for 24 years. For months, Guineans were treated to the spectacle of Camara grilling former government figures on TV, exposing their corruption and mocking their venality. Conte's son and brother-in-law both confessed to being involved in the trans-shipment of cocaine from South America to Europe. Most significantly, Camara also promised to hold democratic elections within a year.

But as time progressed, there was little sign of preparations for those elections. Then came the bloodshed at the stadium. And in October, the junta announced a massive deal with a group called the China Investment Fund (CIF), which promised to fund $7 to $9 billion worth of infrastructure projects in Guinea in exchange for bauxite and iron mining concessions. (Guinea has some of the world's largest bauxite deposits.) Idrissa Cherif, Camara's spokesman, says the first batch of Chinese money has now arrived and will be spent on "electricity, water, roads and the like."

But the opposition is doubtful of the regime's intentions. Oury Bah, head of the opposition party Union of Democratic Forces (UFDG), says the junta is in dire need of cash to pay its supporters. "They need money to stay in power," he says. "They're ready to sign anything." For its part, the opposition is refusing to take part in talks with the junta aimed at creating a national unity government, saying that doing so would only legitimize Camara's rule. As Bah says: "There's no reason to be optimistic."